Take a look at any review of the new Perelman Performing Arts Center (PAC) in New York and there is a good chance the words “$500 million” appear long before the name of any architect, actor, or dancer. The price tag is the headline, and it is impossible to hold a number like that in your my mind without thinking about the recent news of major staffing cuts at the Public Theater and the Brooklyn Academy of Music, or the fact that one of New York’s greatest buildings, Marcel Breuer’s Whitney Museum, will transition from the hands of a nonprofit museum to those of a multinational auction house when Sotheby’s moves in next September (a transaction that, incidentally, sets the market value of Breuer’s masterpiece at about one fifth of the Perelman’s). It is hard not to think about what even a fraction of that half billion might mean to spaces like the Kitchen, the New York Theater Workshop, or Performance Space New York.

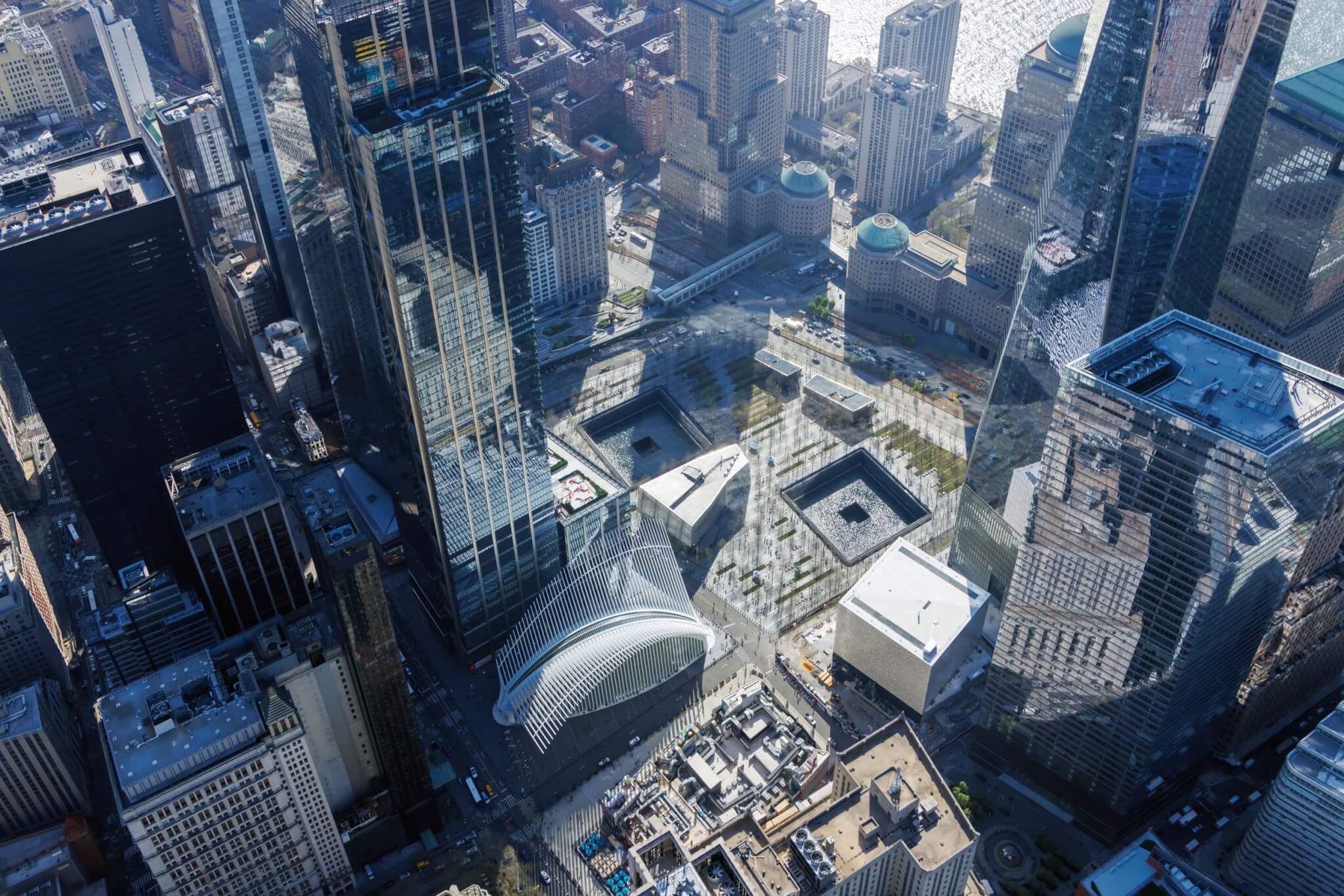

It is hard to know what to make of it all, but there is also little to be gained by begrudging it. This is how money moves in New York and no amount of nostalgia or righteous indignation can stop it. Money flows toward naming rights and ribbon cuttings and development opportunities and speculative investments, and, in this case, toward an awkward little corner of the World Trade Center superblock where a small group of private and semiprivate donors entrusted architect Joshua Ramus to make good on a 20-year-old promise to bring arts to the site of tragedy.

Like most projects on the site, the building advanced in fits and starts. Frank Gehry was hired. Frank Gehry was fired. When Ramus won the commission in 2015, what he was given was not so much a program as a problem: The site sits above a nasty snarl of ventilation ducts, a dozen converging subway lines, and an enormous spiral ramp that delivers trucks to a garage below and, because that ramp needs to rise to street level, most of the PAC begins 21 feet aboveground. To complicate matters, the building can only rest on seven irregularly placed structural knuckles—vestiges of the Gehry design—and it needs to withstand a variety of harrowing blast criteria unique to the site. Furthermore, it was decided somewhere along the line that the theater should not appear conspicuously commercial and the memorial should not be visible from its interior. In short, the design had to be respectful of its context and heart-stirring in its grandeur—simultaneously spectacular and inconspicuous—all while balancing three theaters over a tangle of vibrating infrastructure on a handful of structural points. Given the circumstances, REX’s design is ingenious.

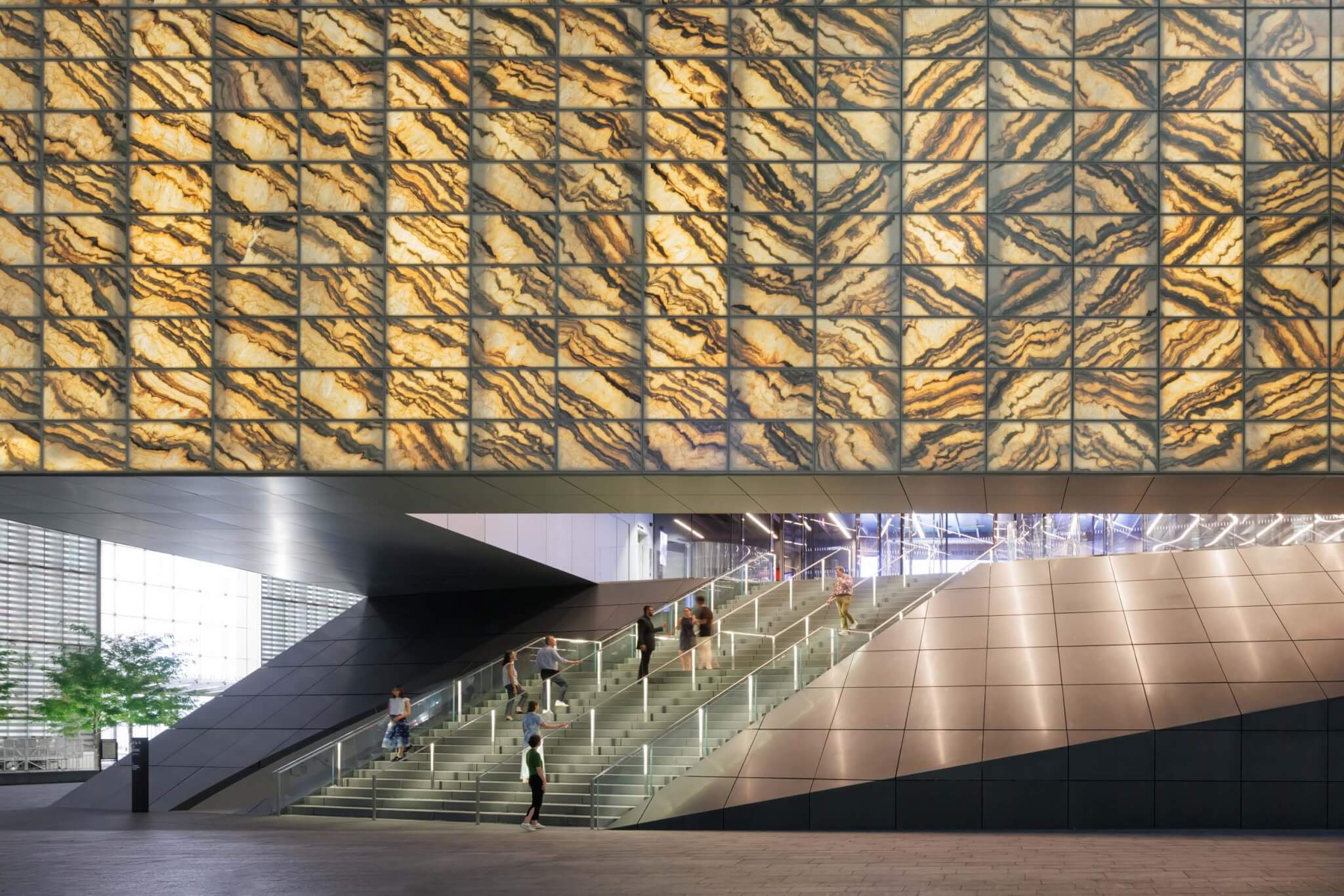

That solution is a cube clad in 4,896 pieces of translucent, intricately veined Portuguese marble suspended above a somber granite plinth. It was developed in partnership with Davis Brody Bond and showcases interiors by Rockwell Group. During the day, the marble washes the interior in warm amber light; at night, it all glows like a creamy incandescent boulder. Nestled inside, and supported by 6,300 tons of structural steel, is a second smaller box containing three theaters arranged in an L shape around a large scene elevator. This trio of theaters can be bisected and bundled in dozens of permutations. To fit it all in, Ramus weaved utilities behind bespoke acoustical panels and turned theatrical convention on its side by stacking the traditional front of house on top of the back (a move he also deployed in his Wyly Theatre in Dallas).

The building invites comparisons with another stone monolith: Gordon Bunshaft’s Beinecke Library at Yale. In both buildings visitors approach at ground level and ascend a staircase to find themselves inside a translucent marble box. The effect, in both cases, is breathtaking, but while the Beinecke reveals itself upon entry—the massive glass column of books articulates what the building does and why it cannot be exposed to direct sunlight—the first floor of the PAC reveals nothing about what is happening in its core. It is a black box in both the theatrical and philosophical senses of the term. You can walk the entire perimeter of the public first floor in the interstitial space behind the marble cladding without a clue as to what is happening upstairs. (Yet some of the building’s nicest moments happen along that perimeter, when you find yourself standing alone between a mundane unmarked door and an exquisite expanse of stone.)

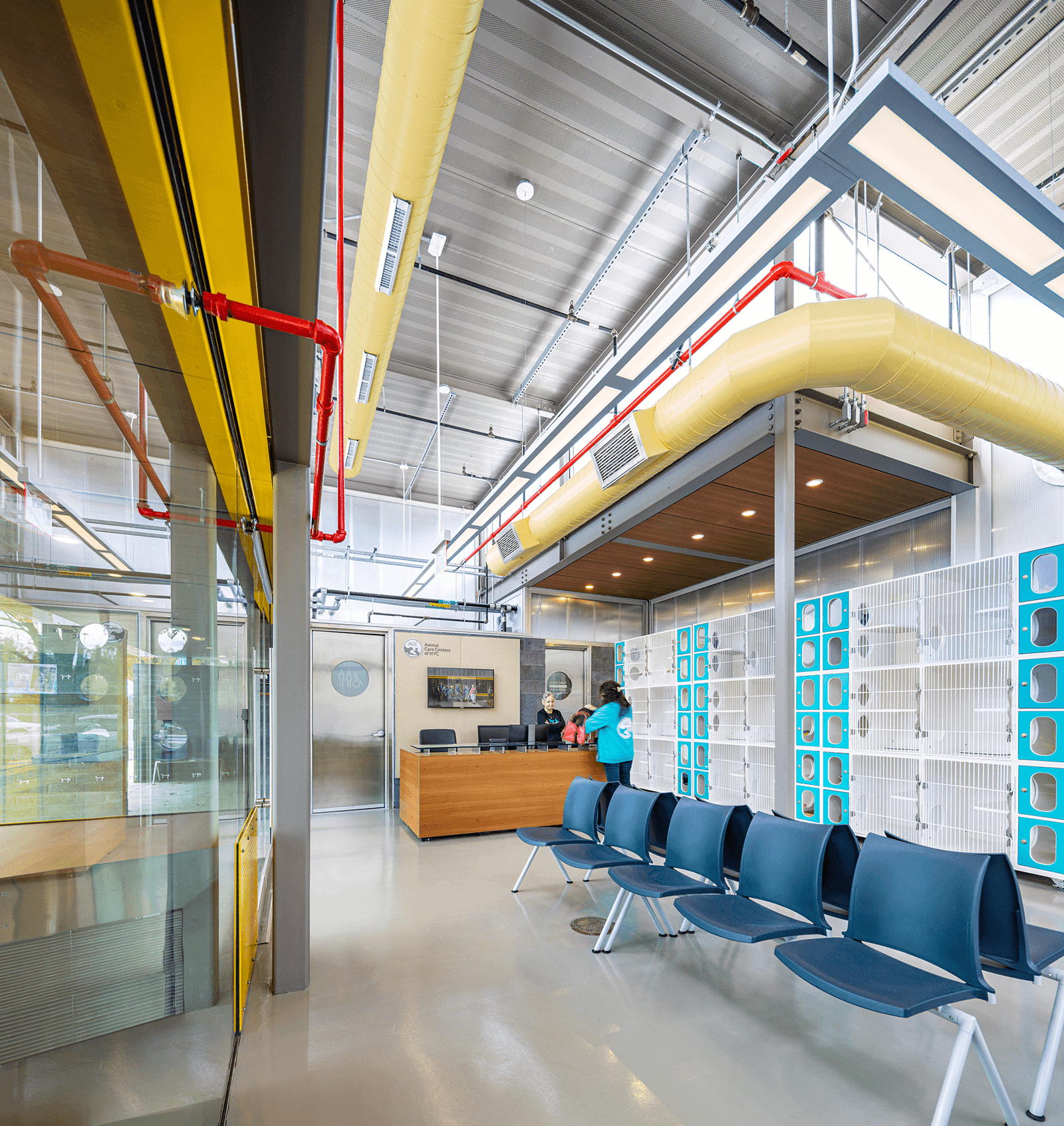

The most exciting space in the PAC is one most people may never see. The day I visited, the lights in the mechanical room beneath the theater were powered down, so Ramus guided me under girders and across catwalks with the flashlight on his phone. Even in the dark I could see the thrill in his eyes as he described how it all worked. Together with several massive “guillotine” walls upstairs, this expanse of collapsible pistons and scissor jacks can push and pull the theaters above into 62 different configurations of thrusts and traps, risers and rakes, pits, and prosceniums (each permutation pre-approved by Port Authority building inspectors). It is here in the building’s mechanized core where it possesses the greatest energy— the same spirit of audacious engineering that pushed the original Twin Towers so high. Fittingly, the PAC was overseen by Magnusson Klemencic Associates, the successor firm of the Seattle-based engineering office that partnered with Minoru Yamasaki on the original World Trade Center.

Beautiful as it is, it is difficult to behold the precision tuning and the ultrafine tolerances of this mechanical room and not feel a shiver of anxiety about what might happen 2 or 6 or 12 years hence when a piston seizes up or a riser gets jammed. Having the capacity to be flexible is not the same as being flexible—and that can be as true creatively as it is mechanically.

Arts nonprofits are delicate organisms and only as strong as the community that surrounds them—a community that needs steadfast supporters and an invested audience just as much as it needs the artists who bring work to life. The PAC has a visionary creative director in Bill Rauch, but he will be working on a site defined by an uncanny dissonance with the city around it. In many meaningful ways, the 16 acres of the World Trade Center site have not been part of New York City since they were seized via eminent domain by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey in 1962. To this day, the superblock remains an island within an island. It has its own police, its own building inspectors, its own rules. It occurred to me as I parted ways with Ramus that a single-minded tourist could take the A train from JFK to Fulton, ascend through the Oculus and walk to the PAC without ever really setting foot on a Manhattan street.

The PAC is the best new building at the World Trade Center, by a long measure, but whether design alone is enough to make the site feel like part of the city remains an open question.

Justin Beal is an artist and author based in New York. His first book, Sandfuture, was published by MIT Press in 2021. He teaches at Hunter College.