With the autumnal equinox less than two weeks away, gallery spaces and cultural venues will soon start switching out their summer exhibitions for their fall and winter offerings. Before that happens, AN’s editors suggest seeking out a handful of shows now on view across the country, stretching from Miami Beach to Reno, Chicago to New York’s Hudson Valley. The below recommendations, including a photographic survey of Paul Revere Williams’ work in Nevada and a decades-spanning showcase of the venerable Pamphlet Architecture, are pulled from the September issue of The Architect’s Newspaper.

And for those on the hunt for a good in-person (!) fall lecture series to populate your calendar with, we’ve also compiled an also-geographically disparate list of public programming at architecture schools from coast to coast.

Pamphlet Architecture: Visions and Experiments in Architecture

‘T’ Space

125 1/2 Round Lake Road, Rhinebeck, NY 12572

Open through October 16

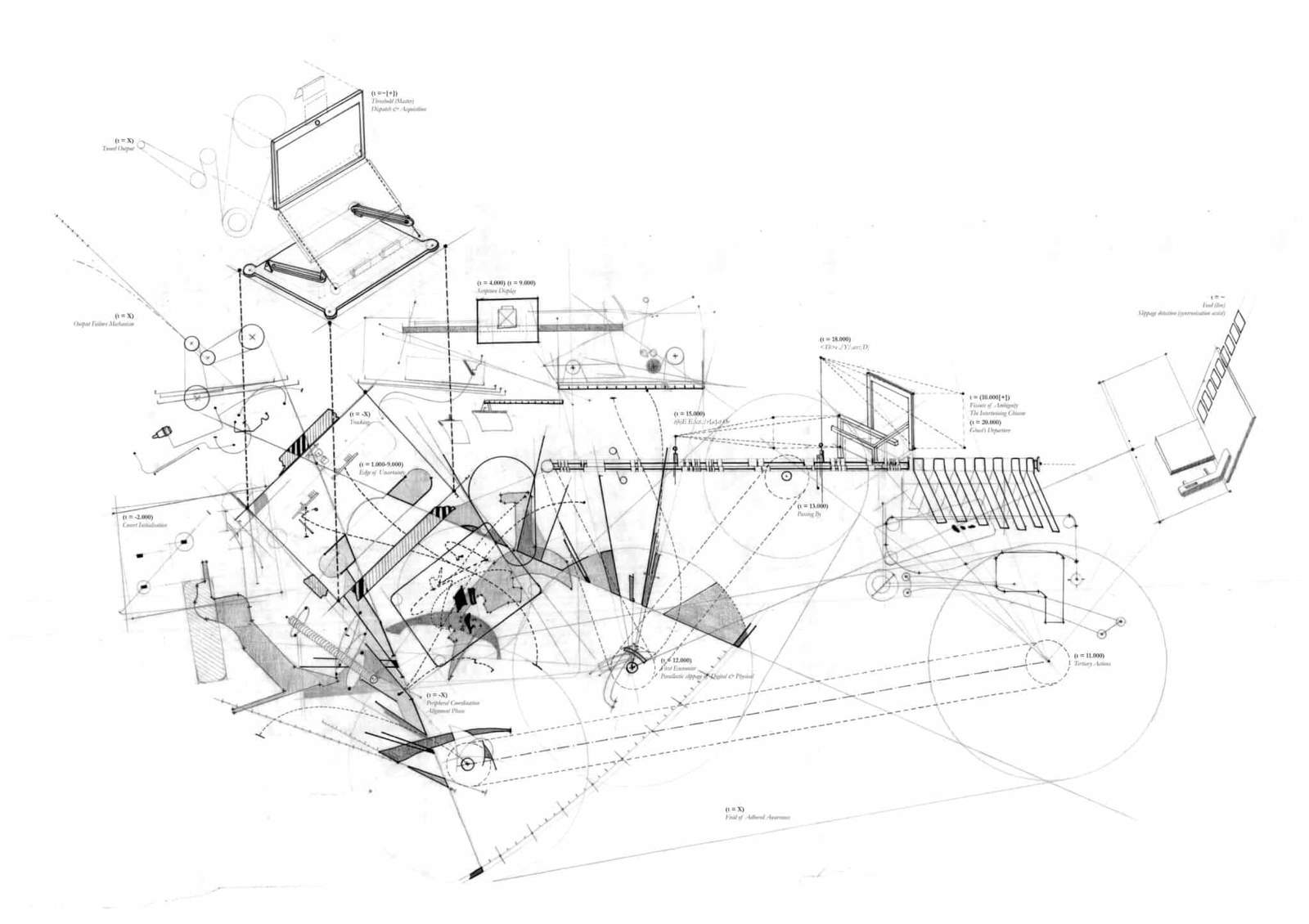

Although its origins can be traced to the 1930s, the zine didn’t come into its own until the punk and postmodern decades of the late 20th century. The form, which celebrated the effervescence of subcultures through brash amateurism, left an indelible mark on the production and marketing of music, film, and comics. By contrast, the zine’s effect on architecture was minimal—unless one considers the Pamphlet Architecture series. Founded in 1978 by architect Steven Holl and noted bibliophile-turned-bookstore-owner William Stout, Pamphlet is best remembered and loved by the cohort whose outré sensibility it embodied, whose freakish talents—think the young Zaha Hadid and Lebbeus Woods—it enshrined and whose intellectual pretensions it flattered. It’s to them, or to their memory (particularly that of the late Kevin Lippert, who agreed to publish the series via his Princeton Architectural Press), that this show is dedicated. Though its best days are far behind it, the project continues: Issue No. 37 is due to arrive this fall. Samuel Medina

The Almighty Church of Abolition

Space p11

55 East Randolph Street, Chicago, IL 60601

Open through September 30

Those in the know will grasp the polemical subtext here (“Almighty Church of Abolition”). How knowledgeable they are about the historical personage at the center of this exhibit, now open at Chicago’s minuscule, underground Space p11 “gallery,” is another matter. From the hardy revolutionary ranks of 20th-century martyrs, curators Daniel Jonas-Roche and Andrew Santa Lucia (both AN contributors) singled out one Alphonse Laurencic (1902–39) for rehabilitation. Working at the behest of Republican Spain amid civil war, the French painter-architect designed prison cells in the basements of desacralized churches to hold fascist POWs; his work sought to purge detainees of their prejudices. For his sympathies, he was executed by nationalists. Jonas-Roche and Santa Lucia update his scheme for our carceral age using paint, projections, colored glass block, and altered ceiling tiles donned with “nine partially revamped perspectives for prison abolition.” They visualize their desires (for social justice or community policing without police) in chockablock fashion here in this subterranean sublation station. SM

Giller & Giller: An Adventure in Architecture

Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU

301 Washington Avenue, Miami Beach, FL 33139

Open through October

Morris Lapidus may have earned the sobriquet “Mr. MiMo,” but he had a challenger for the title. Norman Giller is all but forgotten today, but he was pivotal in establishing the Miami Modern (MiMo) style. The Carillon Hotel, opened in 1958, was the best advertisement for Giller’s handiwork: Plate glass, accordion wall reliefs, a gingerly canopy, and more were brought together in a recumbent beachfront format. The Diplomat Hotel (also from 1958 but now demolished), whose ballroom played host to a late-career Sinatra, sported a hyperbolic porte cochere, which soon became a de rigueur accessory for the typology. Giller & Giller goes beyond this glamorous duo. Giller was astoundingly prolific, building, for instance, thousands of dwelling units for American military bases. His influence was perhaps most keenly felt in the midcentury preponderance of roadside motels. To his credit, he gave panache and frisson—“floating” staircases abound in his catalog—to jobs that privileged expediency over all else. It’s a kind of legacy. SM

Janna Ireland on the Architectural Legacy of Paul Revere Williams in Nevada

Nevada Museum of Art

160 West Liberty Street, Reno, NV 89501

Open through October 2

In February, the Los Angeles City Council added the endangered home of midcentury architect Paul Revere Williams to its monuments ledger. There is little, outwardly, to distinguish the modest Jefferson Park bungalow, except for the fact that Williams lived there. The move is indicative of a cultural reappraisal of one of America’s leading Black architects, who designed thousands of homes, many for Hollywood stars. Since 2016, artist Janna Ireland has crisscrossed L.A. photographing dozens of these residences. Ireland’s camera nestles into the private world of each home while drawing attention to Williams’s incomparable ability to inhabit often-disparate styles. Unlike his white peers, who enjoyed the luxury of having egos, Williams conformed his talents to the desires of his clients. For this exhibition, Ireland captures his Nevada commissions, including the bouncy La Concha Motel (1961) and the faceted Guardian Angel Cathedral (1963), both in Las Vegas. And just as in L.A., she foregrounds the grace the architect bestowed on every one of his dwellings. SM