The Life and Death of Objects

Lars Lerup | Birkhäuser | $36.99

Midway through his Scientific Autobiography (1981), Aldo Rossi muses:

Perhaps the observation of things has remained my most important formal education; for observation later becomes transformed into memory. Now I seem to see all the things I have observed arranged like tools in a neat row; they are aligned as in a botanical chart, or a catalogue, or a dictionary.

It seems appropriate to begin this review of Lars Lerup’s book The Life and Death of Objects (2022) with Rossi’s reflection. For, like Rossi, Lerup has constructed a distinctly compact, chartered, and personal “Autobiography of a Design Project,” a project that readers can follow avidly as the itinerary of a life spent reflecting on, making, and documenting the life and death of objects. We come face-to-face with Lerup’s laser-sharp sensibility. His transatlantic itinerary begins with a telling photograph of the five-year-old Lerup lying on the floor of his parents’ apartment in Vaxjo, Sweden. This image of a child immersed in building an encampment of his own design is magnified by the retinue of scattered items surrounding him, some in place, others waiting to be placed, much like the scene in Ingmar Bergman’s film Fanny and Alexander (1983), where we glimpse Alexander’s enthralled gaze as he imagines a play of his own making.

Lerup’s collection of short narratives takes us on a chronological journey covering vast distances with acutely observed intimacies, all measured by objects of various kinds as they intersect and shape the trajectory of Lerup’s well-spent life. Lerup is an acute observer, and designer, of many of these objects, from a stair to a chair, from an armoire to a table, from a room to the city. Each object becomes a witness, citizen, or protagonist of its author’s obsessions. As the record of a curious and restless mind, the book evokes the manual of a perspicacious engineer, intent in deciphering the enigma and attraction of objects. At other times, Lerup transmits lyrical dispatches from the private journals of a poet. It is this refreshing combination of manual and journal that gives The Life and Death of Objects its captivating rhythm and form.

Though trained in, and conversant with, European and U.S. academies, Lerup’s depictions of the institutions where his intellectual life was shaped do not take center stage but flow to form a continuous visual and emotive landscape. His long tenures at UC Berkley, SCI-Arc, and Rice University provide constant new cartographies waiting to be drawn, often overlooked by the host cities. In Houston for instance, where Lerup was dean for sixteen years of the city’s preeminent school of architecture, he shifted and refocused how the school engaged the city. For better or worse, he brought to light Houston’s unmatched, acritical production of objects across boundless space. Lerup’s engagement was not a head-on collision with the irreverent, convulsive city, but rather a means of positioning Houston as a rich fold for thought and action. Action is echoed across the profusion of drawings and collages that course through Lerup’s narrative. Drawings work like discursive signs at different speeds of development and conclusion, much like the object of all objects: the city.

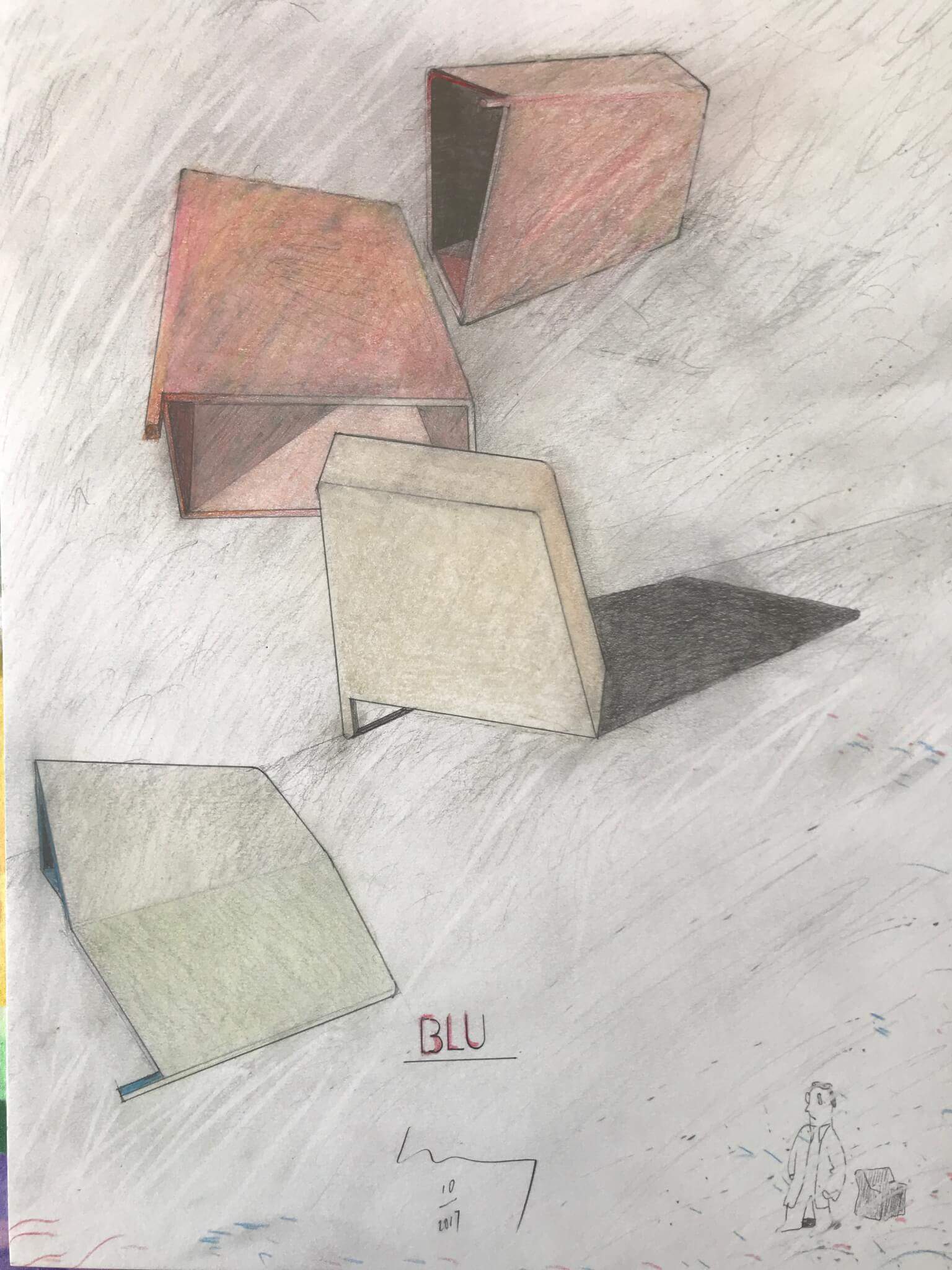

Near the end of the book, Lerup poignantly reflects on Blu, one of his latest objects. It allows him to come full circle in understanding how the objects of his life have become an all-encompassing mirror. This mirror is now a cherished object that fits comfortably in the palm of his hand. Objects have become the traces of life itself. Or as Lerup writes: “For those of us still paranoid and critical, there is no redemption in sight, yet there is in the life and death of things a line of thought that outweighs doom. Here, in and around the small, I have found a cohort whose manifestations espouse no evil, bear no harm. They just want us to see them.”

The book delights readers with Lerup’s honesty and empathy for objects that are often ignored or discarded by our volatile consumerist culture. Lerup is always provoking us to take a second look. His objects bestow a redeeming and forgiving dispensation on our lives, the opposite of those utilitarian contraptions that weight us down with their monolithic authority. Lerup’s objects deserve our respect, our inquiry, our love, and, ultimately, our shared desire for freedom. How else to pause from, or break away from, a world determined to turn us all into profligate, uncritical consumers?

Carlos Jiménez leads Carlos Jiménez Studio and is a professor at Rice Architecture.

A version of this review was previously published in Spanish in Arquitectura Viva on November 1, 2022, as “Objetos liberadores.”