University of Leeds: A Prototype for the Barbican Shows How Brutalist Buildings Can Be Humanised

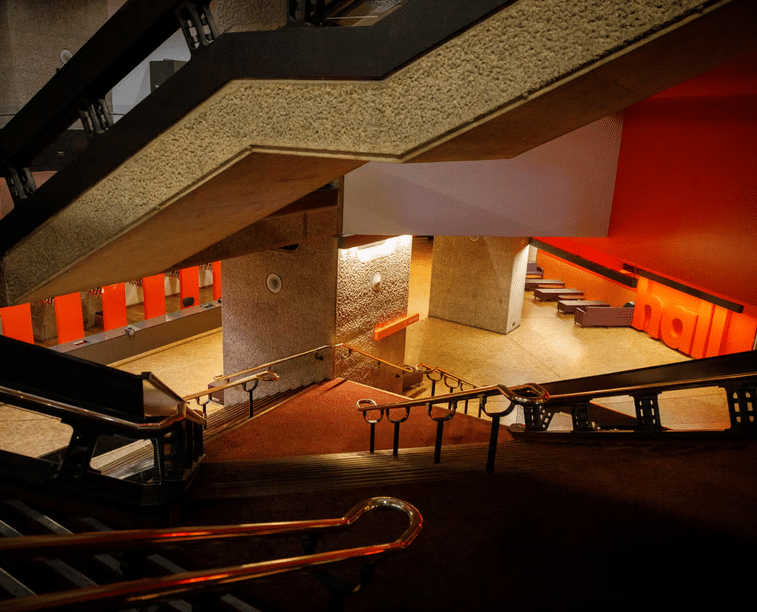

Architectural writer Alan Radford reflected on the refurbishment plans for the Barbican Centre in London, highlighting that the University of Leeds complex served as an early prototype for understanding how Brutalist architecture could evolve from monumental sculptural forms into functional, humanised spaces. Designed by Chamberlin, Powell & Bon in the early 1970s, the Leeds campus included offices, laboratories, a library, and other facilities, anticipating the design and spatial vocabulary of the later Barbican complex.

Brutalism as Art and Architecture

Radford notes that all the design features now familiar in the Barbican were already present in the Leeds complex, including the same challenges related to usability, light, and internal comfort. Initially, he described the buildings as large-scale Brutalist sculpture rather than practical workplaces, emphasizing the aesthetic impact of raw materials, geometric lines, and stark angles characteristic of the style.

Refurbishment as a Humanising Process

Over subsequent decades, the Leeds complex underwent multiple remediation and refurbishment cycles, focused on enhancing usability and improving working conditions without compromising its original Brutalist identity. Radford suggests that those involved in the Barbican refurbishment could benefit from visiting Leeds to see how the university has weatherproofed the buildings and introduced a more human scale and experience into the architecture.

Architectural Takeaway

The Leeds experience demonstrates that, despite their austere appearance and raw materiality, Brutalist buildings can be adapted into functional and human-centred environments, preserving their original design language. This lesson remains crucial for architects and engineers engaged in the restoration of contemporary heritage buildings.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

Alan Radford’s reflection reframes the University of Leeds complex as a formative Brutalist prototype, where monumental concrete architecture first confronted the challenge of inhabitation before the Barbican refined the model. Conceived as sculptural ensembles, these buildings foregrounded raw materiality, weight, and geometry, prioritising visual coherence over immediate comfort. However, decades of remediation reveal a critical architectural lesson: Brutalism’s perceived severity is not fixed but contingent on performance and adaptation. Through incremental upgrades addressing light, weathering, and usability, the Leeds complex demonstrates how Functional Resilience can humanise austere forms without erasing their identity. This process underscores the importance of Contextual Relevance, showing how evolving social and institutional needs reshape architectural meaning. Ultimately, the comparison positions refurbishment as a continuation of Brutalism’s Architectural Ambition rather than its negation.