A memorial for Anthony Vidler and a celebration of 40 years of Parc de la Villette offer reasons for reflection

“Who brought the hankies? It’s going to be a long night,” Liz Diller remarked at the beginning of a memorial for Anthony Vidler held on Saturday, January 27, at The Cooper Union’s Great Hall. Vidler, a beloved professor, architect, author, and former dean, died last October at the age of 82. The event, scheduled for two hours but which ran for three, saw tributes and remembrances by a host of architectural luminaries whose orbits intersected with—or were launched by—Tony’s scholarship and teaching. Many notable attendees were present, including Thom Mayne, Deborah Berke, and even author and photographer Teju Cole.

Giuliana Bruno, a professor at Harvard, recalled when Tony came to her book launch at the Guggenheim Soho, located in the space which later became AMO’s Prada wavy store. (Tony “loved his Prada clothes,” she said.) Bernard Tschumi remembered Tony’s lectures on Boullée, Ledoux, and Lequieu at London’s Architectural Association in the early 1970s. Beatriz Colomina recounted bringing photocopies of his essays with her to the U.S. and that they became wrinkled because she read them so many times.

Peter Eisenman reminded us that he was Tony’s professor at Cambridge University in 1960 and acknowledged that Tony helped with the footnotes to Eisenman’s dissertation: These days, “you got to be very careful with who did what,” he admitted. Later, Tony would join Eisenman and Michael Graves to propose a linear city for New Jersey, which predated both Superstudio and NEOM; work together at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies; and edit Oppositions. Nader Tehrani recalled lunches of light salad and whiskey after faculty meetings. (Later dates dispensed with the greens and opted for just the sauce.) As a dean, Tehrani thrived on chaos while Tony avoided confrontation. On Tehrani’s last visit with Tony in the hospital, he still wanted the latest gossip; he had a thirst to be in the thick of it. Mary McLeod reminisced about how Tony encouraged her to get into architecture and later advised her dissertation at Princeton.

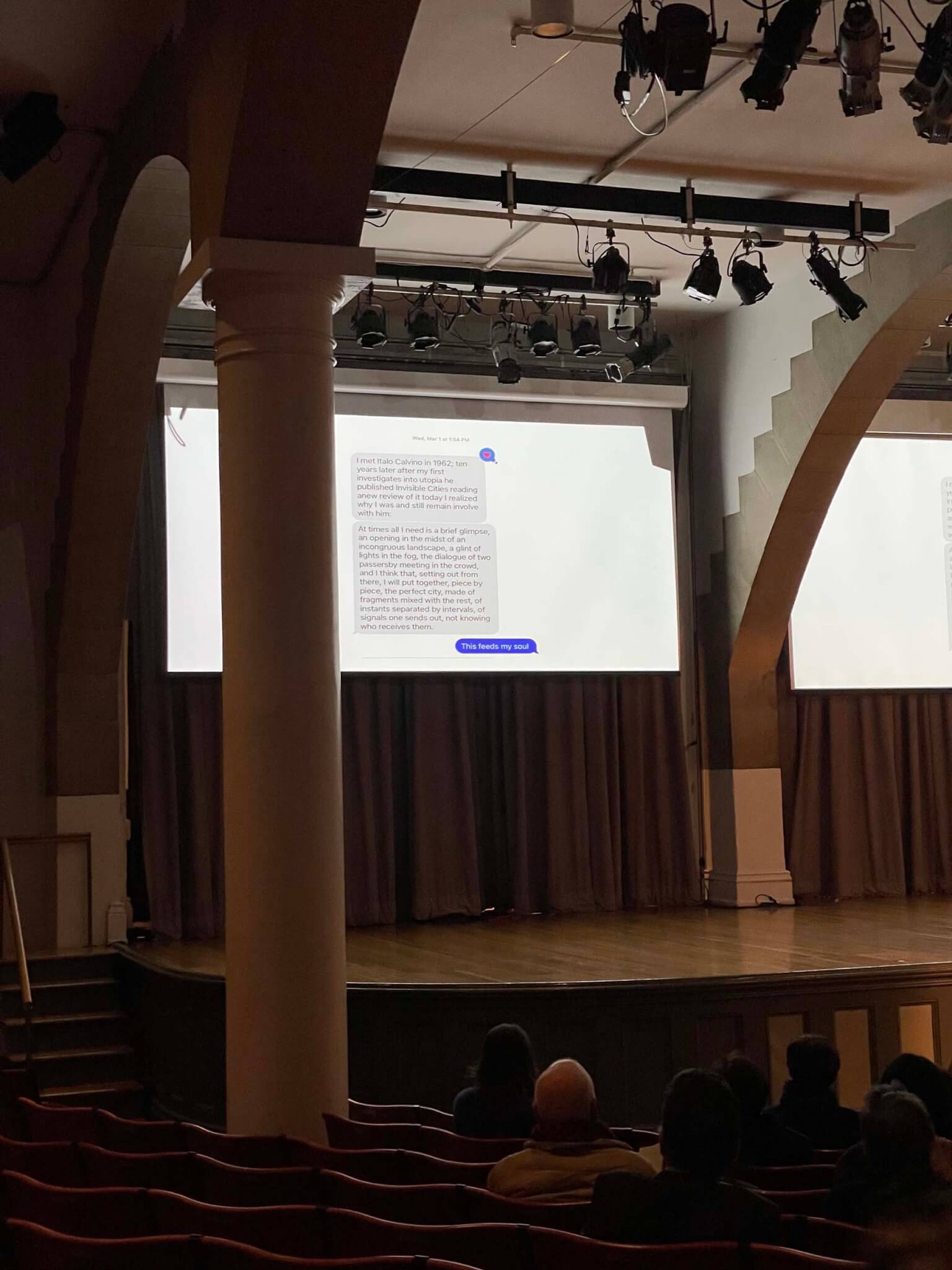

Later, Spyros Papapetros recalled how Tony, when in the hospital, brandished his tray as both a writing desk and a drawing table. Lydia Kallipoliti began with a meme-like alteration of the I ❤️ NY logo into one for Vidler: I ❤️ TONY. She shared screenshots of text messages about utopia before ending with a funny video of Tony, an Englishman, imitating sociologist John McHale, a Scotsman, for a 2016 symposium.

Mark Wigley, who spoke at the end before Tony’s son Nicholas and wife Emily, took the opportunity to lightly roast the occasion. At this “festival of sadness disguised as synchronized celebration,” no one was willing, it seemed, to mention the “envy, jealousy, and resentment” that powers the work of architecture academics. Referencing the three display screens that showed the same slide behind him, the hall became “a small room trying to seem bigger than it is, filled with small people trying to be bigger than they are.” To insult this “room full of people who think buildings talk” may feel harsh, but Wigley’s act was, he claimed, a way to show his love for Tony, a treasured figure, who thought long and hard about what architecture discourse hides.

Wigley also spoke the following Thursday (February 1) at the Wood Auditorium uptown at Columbia GSAPP’s 40th birthday party for Tschumi’s design for Parc de la Villette, which won its now-famous competition in 1983. The park opened in 1987, just before the architect became the school’s dean. (He stepped down in 2003.) Here Wigley, who followed Tschumi as dean, was more complimentary: He toasted the embarrassingly successful park’s hospitality to promiscuity and called it “the park that invented Bernard.”

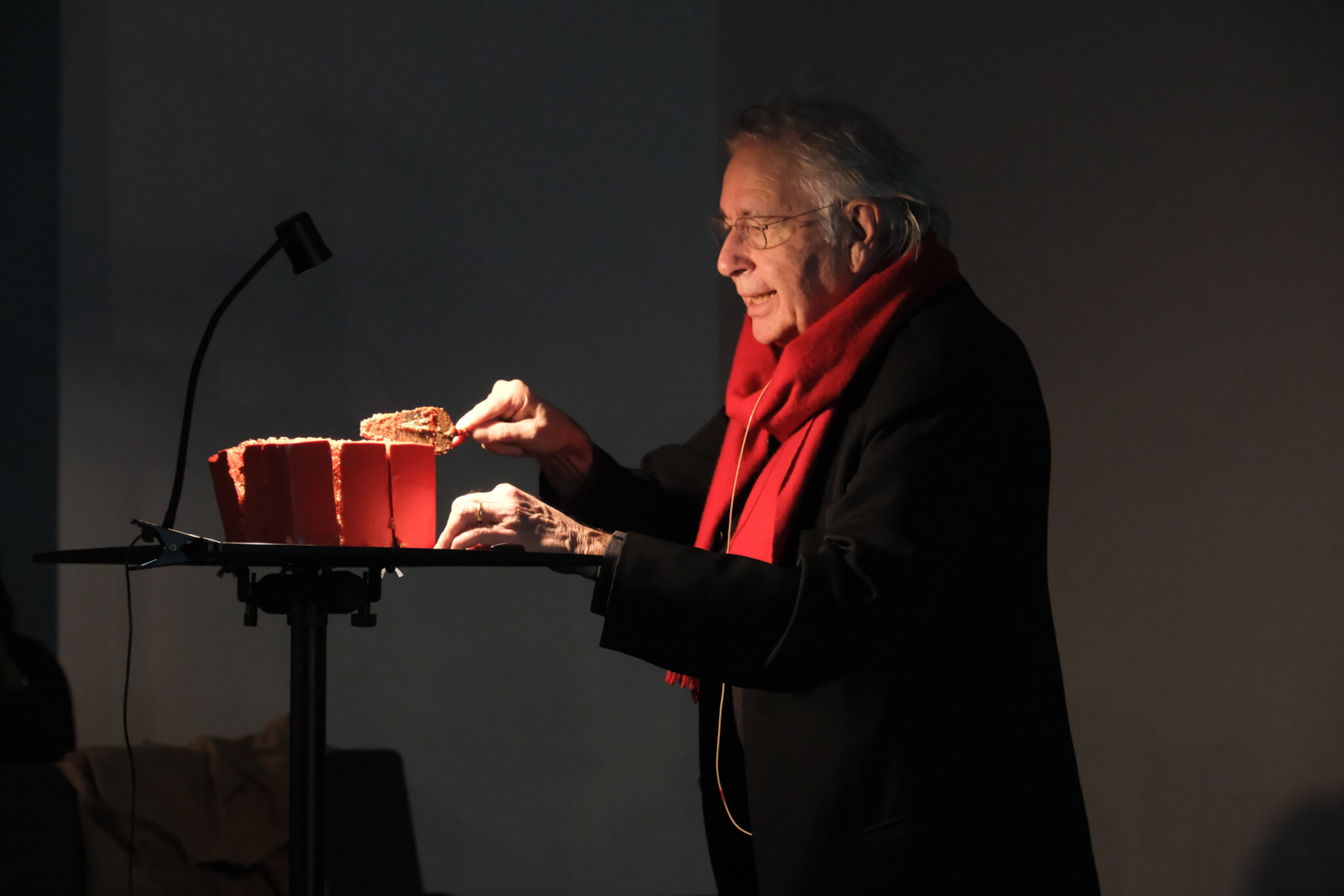

For this festive event, a grid of cubic cakes faced in red icing were placed across the darkened auditorium, each elevated on a tripod and illuminated with a clip light. Food and drink were at the front, and a DJ spun club music. Event assistants were wearing custom t-shirts, and many guests, in sartorial alignment, wore red. The night’s offerings were spoken in the round and addressed to Tschumi who sat perched in the audience. Current dean Andrés Jaque began with an obvious question: Which came first, the red scarf or La Villette? The project was informed by George Bataille’s notion of transgression, though the politics of the era are different than ours. Still, the activity-rich expanse serves to “multiply the spectrum of the possible.”

Tributes followed. Mimi Hoang recalled seeing the project as a clueless undergrad, and it made an impact. Michael Bell wagered La Villette is the “largest building ever,” and, quoting Foucault, posited that “freedom is a practice not a form.” Steven Holl remembered seeing early drawings for Tschumi’s entry and provided blunt feedback: “If you don’t put more trees in the drawings, you’re not going to win this competition.” Reinhold Martin wondered about the meaning of red and compared the project to Eisenman’s memorial in Berlin. Mario Gooden recalled a film of the architect hanging from a structure in mid-air—“Bernard wasn’t supposed to be athletic; he’s a theorist”—before citing the need for intellectual joy. Jing Liu remembered the red scarf she wore as a child in China. Rachaporn Choochuey, a GSAPP alum, shared a student memory of when Tschumi’s scarf went missing. Jimenez Lai, in from L.A., expounded on the function of uselessness. Jerome Haferd, who reminded us he was not alive when Tschumi won the competition, challenged us to imagine new epistemes. What are the La Villettes for the next 40 years? Galia Solomonoff worked for Tschumi in the 1990s and described a holiday where she went into the office to get ahead, only to witness Bernard, headphones in and tunes blasting, arrive for a sketch sesh. (She ducked under her desk and snuck out the back before he could notice.) Here’s to dancing when nobody’s watching.

Laurie Hawkinson read Peter Wilson’s review in AA Files that compared it to another now-famous competition win that same year: The Peak in Hong Kong by Zaha Hadid. Wonne Ickx gave a short reading of nonsense lines from Archizoom’s No-Stop City, an endless plan made on a typewriter, praising its drawing as notation. Tschumi’s gift was to allow us to read things the wrong way, he said. Then Bart-Jan Polman recalled modeling the follies in Maya as a student at TU Delft before handing the mic to the final boss: “With that, Bernard, the grid is yours.”

Tschumi—a shock of white hair above a wrapped red scarf, once a young activist and now dean emeritus—said he wouldn’t answer the question about why red. But he did say the goal all along was to turn the city into a generator of culture. He was about to cut the cake when, with some theatricality, he stopped to draw on its top, the tip of his pen turning red with icing. Then he sliced the cake into three layers of nine-square grids, or 27 cubes. “I will start with the most difficult part of the building: the corner,” he cried, before popping it into his mouth. To really appreciate architecture, you may even need to eat it.