The upcoming Architizer Vision Awards celebrates the brilliant creators that take a project from concept to construction and beyond. With prizes honoring the minds behind architectural photographs, videos, visualizations, drawings and models, we’re making making an expanded definition of Architecture mainstream. Learn more and register:

Register for the Vision Awards

Architecture is the art of defining spaces. The boundaries between this room and that, the kitchen and the living area, the interior and the exterior; in short, the distinctions that give meaning to our homes, workplaces, and cities were all thought up by architects. We know this, of course, but as we move through our day, it is easy to forget. Rooms, buildings, street corners and the rest have a way of fading into the background, of seeming like they sprouted out of the ground like mushrooms. But they didn’t. They were created by human beings, and, like all human-made things, they tell a story.

The role of architects in authoring space is perhaps more apparent in some places than others. Residents of Hiroshima, for instance, a city that was violently destroyed and had to be rebuilt, are aware that the spaces they inhabit didn’t emerge through a gradual, quasi-natural development process. There was a moment when history entered the picture and leveled centuries of accumulated growth and another moment when the decision was made to rebuild. After this, a series of moments — of decisions — defined how Hiroshima would adapt to the postwar period and what relationship the city would have to its past.

Much of the intellectual and creative work that went into defining the new Hiroshima is invisible today, of course, to most people who move through the modern metropolis. But for those listening, the ghosts are hardly silent.

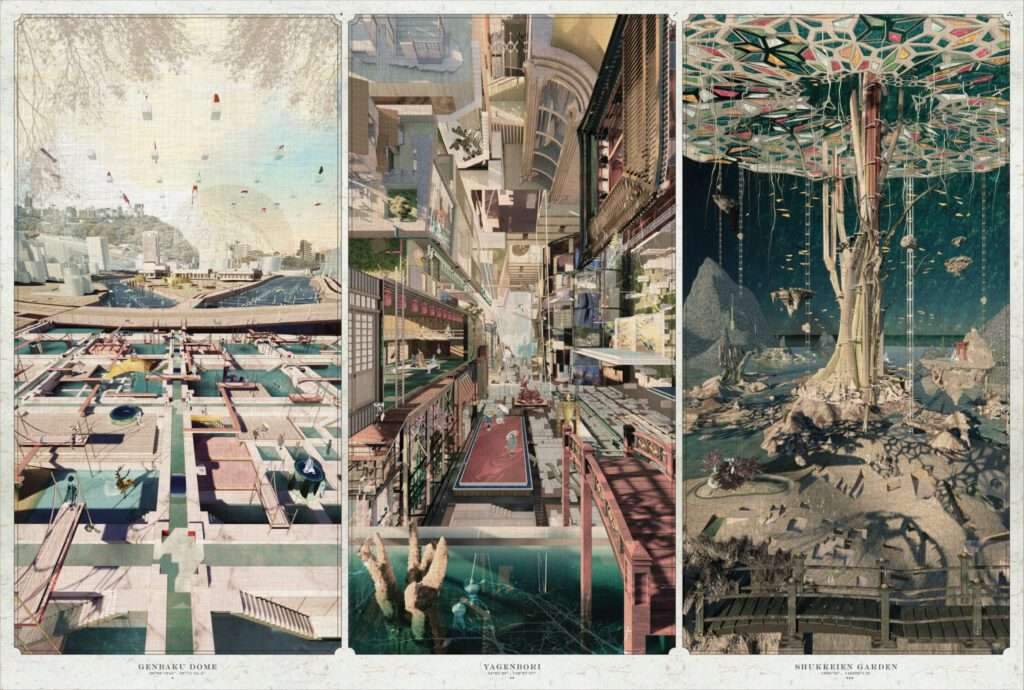

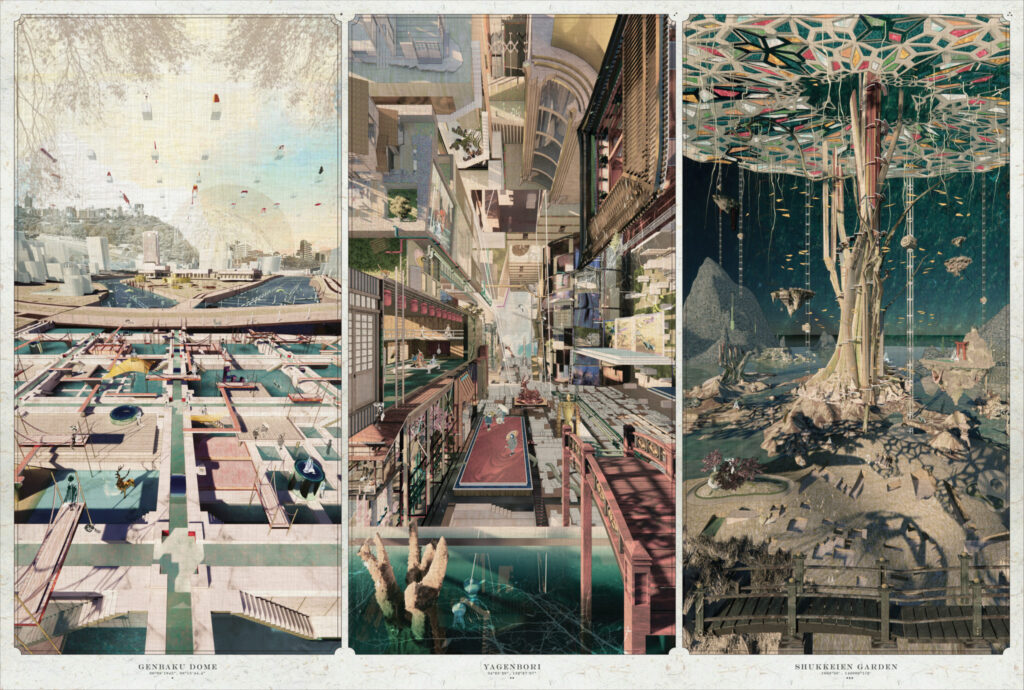

The above ideas aren’t my own. Not exactly, anyway. They were inspired by my contemplation of Victoria Wong’s magnificent triptych Into the Void: Fragmented Time, Space, Memory, and Decay in Hiroshima, the 2022 Student Winner of Architizer’s One Drawing Challenge. Anyone who gazes at this intricate, hallucinatory piece, which evokes at once Hieronymous Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights and the floating worlds of Hayao Miyazaki’s animated films, can see that this is a work of imaginative art.

They might not immediately regard it as an “architectural drawing” according to the way the term is usually understood. But this work is an architectural drawing in the more important sense; that is, it is engaged with the questions architects deal with every time they undertake a project, no matter how humble. The illustration explores the relationship between the past and the future and how each new addition to a city is an event in its ever-evolving story.

Wong, an architecture student at the University of Michigan, put it this way in her artist’s statement: “Architecture is essentially an internalization of society yet an externalization of ourselves. This triptych adapts Japanese aesthetic theories of transience & imperfection, and applies them to the city of Hiroshima. Through investigating the decay & death of artifacts and events, Into the Void illustrates the new collisions of regrowth and reshaping our relationship with different agencies.”

Agencies is a key term here. The work grapples not only with history as something that “happened,” but with the agents who shaped history, which in Hiroshima’s tragic case includes architects of destruction as well as construction.

The leftmost panel of the triptych is titled “Genbaku Dome,” the common name given to the ruins of the Jan Letzl designed Product Exhibition Hall, which was one of the only structures left standing in Hiroshima after the 1945 atomic bomb attack that leveled the city and left 140,000 people dead. Today, the dome is preserved in its ruined state and serves as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial at the center of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

The leftmost panel of the triptych is titled “Genbaku Dome,” the common name given to the ruins of the Jan Letzl designed Product Exhibition Hall, which was one of the only structures left standing in Hiroshima after the 1945 atomic bomb attack that leveled the city and left 140,000 people dead. Today, the dome is preserved in its ruined state and serves as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial at the center of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

The shape of the Product Exhibition Hall is visible in the middle distance on the left side of the panel. It is not a ruin here but a clean white volume, evoking an early digital rendering. The imprecise outline of the dome appears again in the background of the composition like a massive rising sun. Up in the sky, dozens of unidentified flying objects, also clean white volumes like the Product Exhibition Hall, move toward the drawing’s vanishing point in orderly rows, disappearing behind the ghostly sun-dome. The mixture of more and less detailed areas of the composition give the sense of a city overlaid with both memories of the past and visions for the future.

The center panel, titled “Yagenbori” after Hiroshima’s red light district, continues this theme of fragmented and overlaid temporalities. There is also a warped, Escher-like play with perspective, as if now space as well as time has cracked. One feels as if they are at once looking down from the top of a skyscraper and out into a street from ground level.

The center panel, titled “Yagenbori” after Hiroshima’s red light district, continues this theme of fragmented and overlaid temporalities. There is also a warped, Escher-like play with perspective, as if now space as well as time has cracked. One feels as if they are at once looking down from the top of a skyscraper and out into a street from ground level.

The line between interior and exterior is blurred now as well, to powerful effect. A seemingly modern skyscraper has missing walls, allowing the viewer to see inside, where they find a traditional Japanese interior, with bamboo screens and elegantly dressed women carrying parasols.

The rightmost panel is the most abstract and stunning. Titled “Shukkein Garden” after a historic public garden, the composition is dominated by a massive tree that echoes the shape of a mushroom cloud. The canopy seems to be made from stained glass and the tree is orbited by floating islands. What I see here is an eco-utopian image of the future, a tree of life reminiscent of the Tree of Souls in Avatar, which is at once a habitat and an archive of the Nav’i’s accumulated wisdom, a living Internet.

This panel speaks to the impossibility of adequately representing either the horrors of the past or the possibilities of the future. Adorno famously said there could be no poetry after Auschwitz; this panel suggests there needs to be poetry, or at least the attempt at poetry in the wake of unimaginable destruction. The future beckons and enchants, even as the past has not been adequately reckoned with.

The possibilities of architectural drawing are endless once the artist frees themself from the idea that they are drawing buildings. They are not, not really, even when they literally are. They are drawing the ideas that the buildings embody: what they represent to the past, the present, and the future.

The upcoming Architizer Vision Awards celebrates the brilliant creators that take a project from concept to construction and beyond. With prizes honoring the minds behind architectural photographs, videos, visualizations, drawings and models, we’re making making an expanded definition of Architecture mainstream. Learn more and register:

Register for the Vision Awards