The Future of Living: Housing Beyond Ownership, Construction, and Habit

If the world is changing, it would be intellectually dishonest to assume that housing will remain untouched. Throughout history, architecture has never led social transformation; it has always followed it. When theorists, technologists, and public figures speak today about a future without poverty, without traditional currencies, or without conventional labor, the architectural question inevitably follows: what happens to the house?

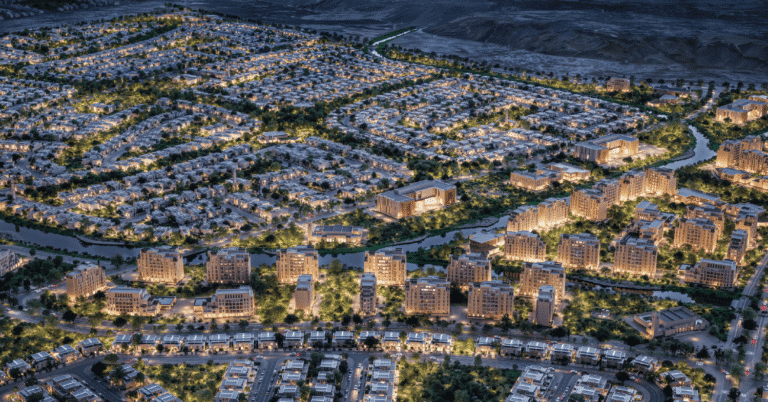

“By 2026, the future of housing is no longer a theoretical horizon but a measurable constraint system. Global outlooks from McKinsey, the World Economic Forum, and UN-Habitat converge on three signals that architects can no longer ignore: modular and off-site construction is projected to capture roughly 20–25 percent of the residential market by 2030, low-carbon material systems are already demonstrating 30–50 percent reductions in lifecycle emissions compared to conventional housing, and the global affordable-housing gap is on track to exceed 300 million units within the next decade. These are not abstract forecasts; they are pressures reshaping who gets commissioned and who is sidelined. For housing architects today, relevance will depend on mastering scalable systems, high-density affordability, and adaptive reuse rather than bespoke singularity. The profession’s advantage will lie in its ability to integrate AI, data modeling, and lifecycle economics early in design, transforming housing from a static product into a continuously optimized social infrastructure.”

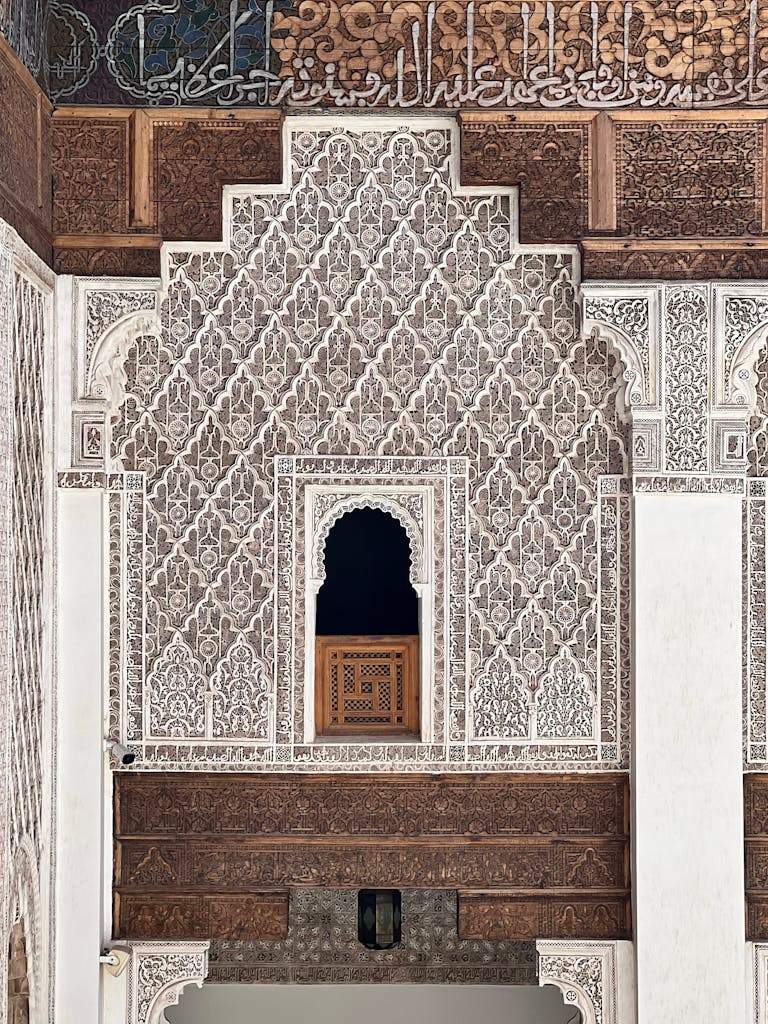

Housing has never been a static concept. It evolved not because architects reimagined it, but because societies redefined what they needed from it. The Roman Coliseum itself was partially dismantled over centuries, not out of ignorance, but out of necessity. Stone by stone, its fabric was repurposed to build homes for surrounding communities. Heritage, as we understand it today, did not exist then. Shelter did. This historical moment matters because it reveals a constant truth: when housing becomes urgent, symbolism collapses.

The contemporary moment carries a similar tension. Younger generations consume space differently. Screen time has replaced physical proximity. Social interaction has migrated indoors, and often into digital environments. The house is no longer merely a place of rest; it has become an interface. This shift is already visible across Architecture and Cities, where residential layouts quietly adapt to hybrid lifestyles that blend work, leisure, and isolation.

At the same time, the construction logic underpinning housing is under scrutiny. The traditional model—reinforced concrete, steel frameworks, prolonged site labor, layered subcontracting—reflects an industrial mindset rooted in abundance of manpower and time. That model is increasingly misaligned with economic reality. Labor shortages, rising material costs, and compressed delivery schedules are pushing housing toward prefabrication, modular systems, and off-site assembly. What appears today as a trend of “container homes” or modular units is not a stylistic movement; it is an economic response.

Yet modular housing raises deeper questions. Where does it land? Land remains the most immovable constraint in housing economics. As cities expand and infrastructure costs rise, land ownership becomes increasingly inaccessible for average households. This is not speculation. It is a measurable trajectory across global real estate markets. Housing, therefore, is being decoupled from land ownership. Leasing, shared developments, vertical density, and adaptive reuse are becoming more relevant than suburban expansion.

This decoupling forces architecture to confront a difficult reality: the future home may not be permanent. It may not even be owned. The idea of housing as a lifelong asset is weakening, particularly among younger generations who value flexibility over accumulation. This shift challenges traditional Projects logic, where long-term value was tied to fixed typologies and static use.

Technology accelerates this transformation. Just as the automobile evolved from mechanical object to electric and autonomous system, housing is evolving from static enclosure to responsive environment. Smart systems, energy optimization, and AI-driven environmental control are redefining comfort itself. The question is no longer how big a house is, but how intelligently it performs.

Artificial intelligence plays a critical role here. AI does not merely optimize layouts or generate renderings. It reshapes decision-making. It predicts maintenance, anticipates user behavior, and informs lifecycle performance. In Building Materials research, AI-assisted material selection is already influencing durability and cost-efficiency. The house of the future will not be designed once and left alone; it will be continuously adjusted.

Work patterns reinforce this shift. The office, once a central anchor of urban life, is losing its inevitability. Companies operating with minimal physical presence demonstrate that productivity no longer requires centralized space. When organizations can function with distributed teams, vast office inventories become redundant. The architectural implication is unavoidable: office buildings will either transform or decay.

Adaptive reuse emerges as a housing strategy rather than an architectural luxury. Converting underused office towers into residential units is not a design challenge alone; it is a regulatory and infrastructural one. Ceiling heights, daylight access, and service cores were not designed for living. Yet economic pressure will force cities to solve these problems. Housing demand will not wait for perfect typologies.

What emerges from this convergence is not a single future, but multiple housing futures. Dense urban living will intensify in some regions, while modular and semi-mobile housing expands in others. Rural depopulation may reverse selectively as connectivity replaces proximity. Villages may shrink, but networks will grow.

The role of the architect within this future is no longer confined to form-making. Architects become system designers, mediators between land economics, construction logic, and human behavior. Housing is no longer about providing rooms; it is about orchestrating living conditions across uncertainty.

This is why discussions about the future of housing cannot be reduced to trends like micro-homes or smart apartments. These are symptoms, not causes. The real transformation lies in how societies value permanence, ownership, and spatial identity.

Ultimately, housing has always reflected how humans relate to time. Past generations built for inheritance. Future generations may build for adaptation. Architecture does not decide this shift, but it must respond to it intelligently.

The future of living will not be defined by materials alone, nor by technology alone. It will be defined by how well architecture understands the evolving relationship between people, land, labor, and meaning. And in that sense, housing remains architecture’s most consequential responsibility.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

Framed as a projection into the near-future, this article examines housing architecture in 2026 through four powerful drivers: material inflation, zoning shifts, emerging technologies, and global migration patterns. The organizational clarity—dividing the narrative into economic, spatial, technical, and human aspects—helps ground what could have been a speculative piece. Architecturally, the piece shines when highlighting contradictions: green ambitions versus unaffordable execution, or digital dreams versus regulatory stagnation. However, it stops short of interrogating the moral implications of housing becoming a “tech product,” nor does it challenge who benefits from AI-generated prefab homes. Unlike deeper essays such as “The Price of Integrity”, the article skirts around the ideological stakes of this shift. Still, it remains a timely architectural mirror—held up to a world where shelter, once a right, is fast becoming an algorithm.