How to Transform an Initial Sketch into a Diplomatic Identity: The Story of Designing the New Indonesian Consulate in Jeddah

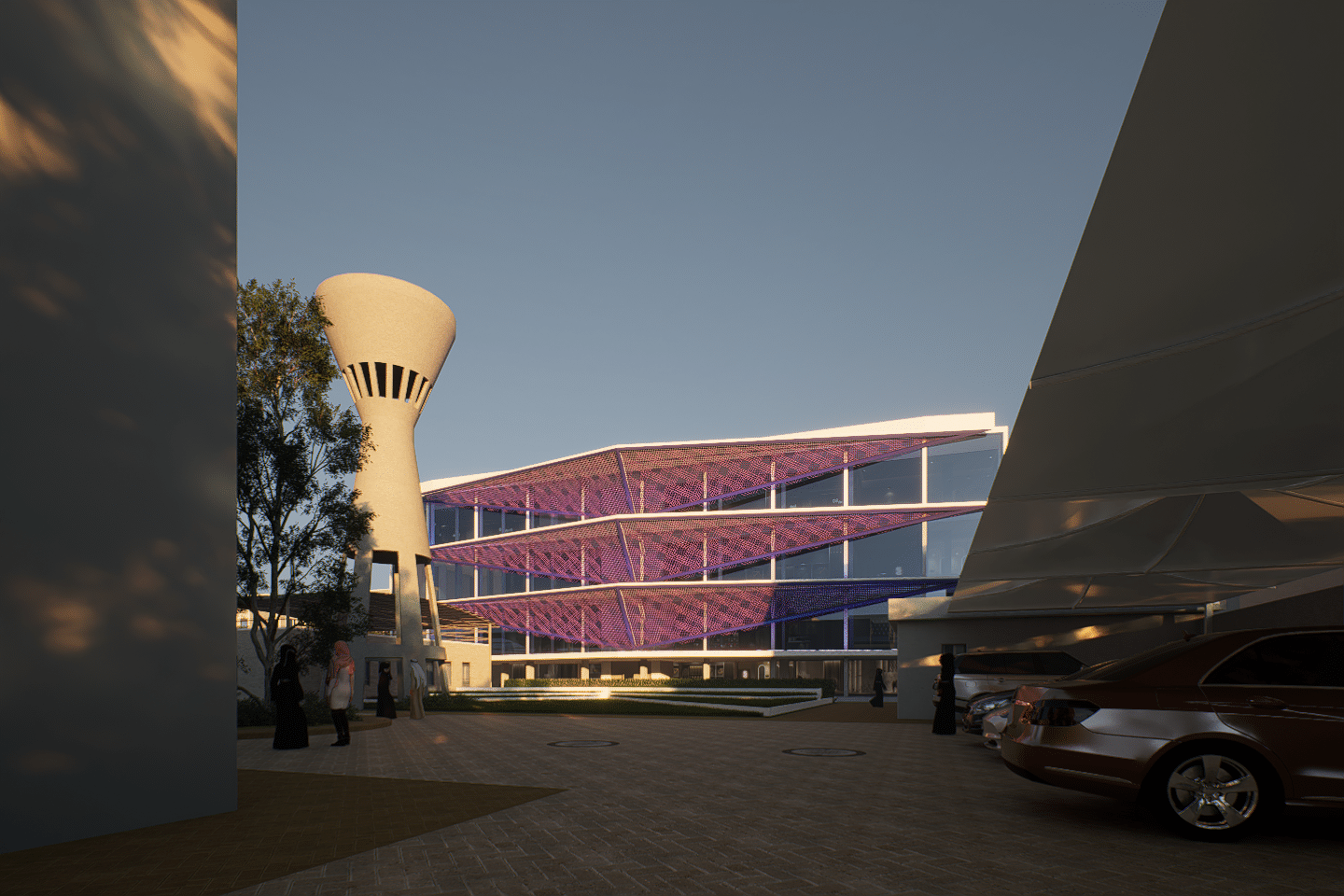

The new Indonesian Consulate in Jeddah did not begin as a finished design or a final image seeking execution. Rather, it started as an open-ended exploration of what diplomatic architecture means within a city carrying religious, cultural, and economic significance like Jeddah. From the very first moment, the question was less about form and more about function: How can a diplomatic building be a symbol without being a statement, an identity without being a repetition?

This question guided Saudi architect Ibrahim Nawaf Joharji to adopt a design approach based on iterative development, cultural research, and mathematical analysis, rather than visual replication or direct ornamentation.

The First Sketch: A Directional Stroke, Not a Final Image

The project’s first sketch was neither a façade plan nor a complete mass; it can be described as a “directional stroke.” An initial line defining the relationship between the site, the street, the building mass, and the surrounding space. At this stage, the goal was not to achieve a beautiful form but to test the idea of presence: Should the building announce itself, or gain its strength from balance?

This sketch served as a starting point for three subsequent development phases, in which the concept was deconstructed and reconstructed multiple times until the project settled into its final massing. What distinguishes this stage is that it was not a search for an icon but an attempt to understand the diplomatic context before the architectural one.

Three Development Phases that Shaped the Identity

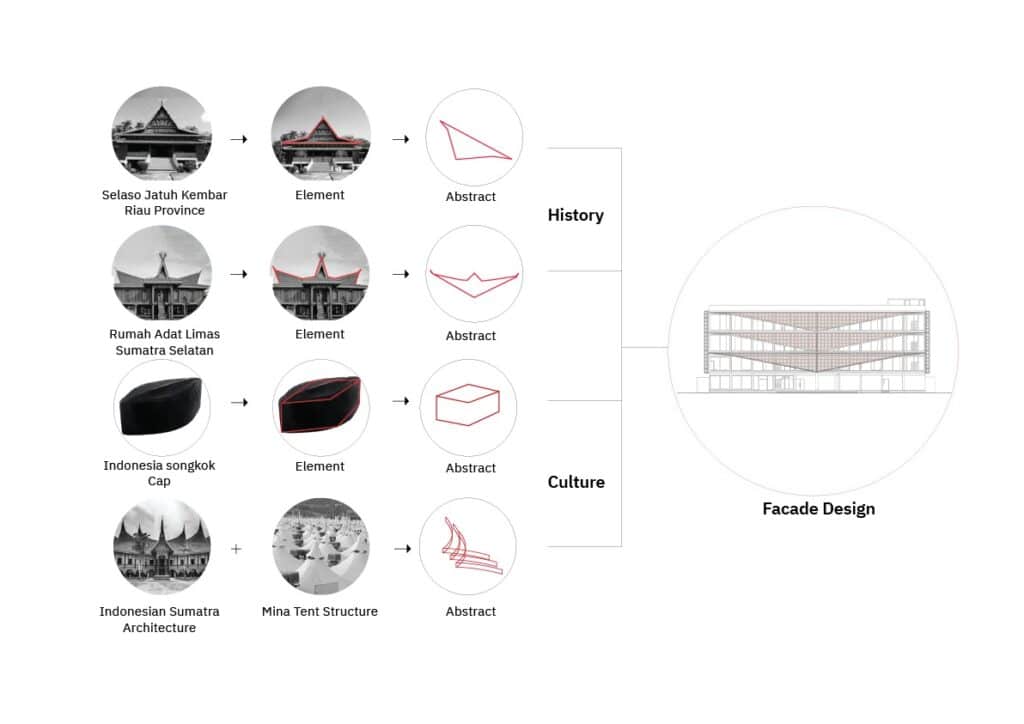

The design underwent three major transformations. In the first phase, Indonesian cultural references were abstracted from their literal forms and converted into relational proportions. In the second phase, the geometric mass began to be stabilized using precise mathematical ratios, through proportional systems that stabilized the massing, giving the building a clear visual balance without resorting to direct symbolism. The third phase was the most sensitive, as the form was fully adapted to climate requirements, sun orientation, and wind movement, leading to a recalibration of the façade and interior spaces according to environmental performance.

This phased development made the final form a logical outcome of a series of decisions, rather than a product of personal taste or formal preference.

Batik: From Ornamentation to a Mathematical System

One of the most complex aspects of the project was handling the Indonesian batik. Instead of choosing a single pattern and enlarging it on the façade, the batik was analyzed as a system rather than as mere decoration. The study involved three different layers of batik patterns, representing multiple regions and cultures within Indonesia, which were then integrated into a single geometric system.

The analysis revealed that the batik does not function as a homogeneous grid, but as adjacent geometric islands, each with its own internal logic. This concept became the generative basis for the façade, where a three-dimensional shading system was designed using asymmetrical repetition, maintaining rhythm without falling into monotony.

The result was not a decorative façade but a functional architectural envelope that reflects culture through logic rather than literal form.

Between 19 Saudi and 28 Indonesian Styles

The cultural context of the project was not one-dimensional. Today, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia recognizes around 19 local urban styles, each with characteristics linked to geography and climate. In contrast, Indonesia comprises more than 28 traditional architectural styles, shaped across thousands of islands and wide environmental and social variations.

A conceptual analysis diagram illustrating the creative evolution of the project. It explicitly breaks down the four cultural inspirations: the “Selaso Jatuh Kembar” roof, the “Rumah Adat Limas,” the iconic black velvet “Indonesian Songkok Cap” (Peci), and the “Mina Tent Structure.” The diagram visualizes how these physical elements were abstracted into geometric lines to generate the final dynamic, multi-layered facade design shown on the right.

The project did not attempt to represent this diversity literally; rather, it sought to establish a common language capable of encompassing it. This language was geometric, based on proportions, repetition, and gradation, allowing the building to be Indonesian in spirit and Saudi in context without contradiction.

Sustainability: A Design Decision, Not an Afterthought

From the earliest stages, the project was fully developed using Building Information Modeling (BIM). This methodology was not only used for engineering coordination but served as a key environmental analysis tool. Airflow, wind direction, sun angles, and energy efficiency were tested at every development stage.

The parametric façade was shaped not by aesthetic desire but as a result of careful study of sun-exposed surfaces, with shading density increased in critical areas and reduced in less exposed zones. This gradation not only enhanced thermal performance but also provided the façade with a variable visual depth throughout the day.

Energy efficiency was a core objective, not merely as a technical requirement but as part of the diplomatic responsibility of a building representing one country within another.

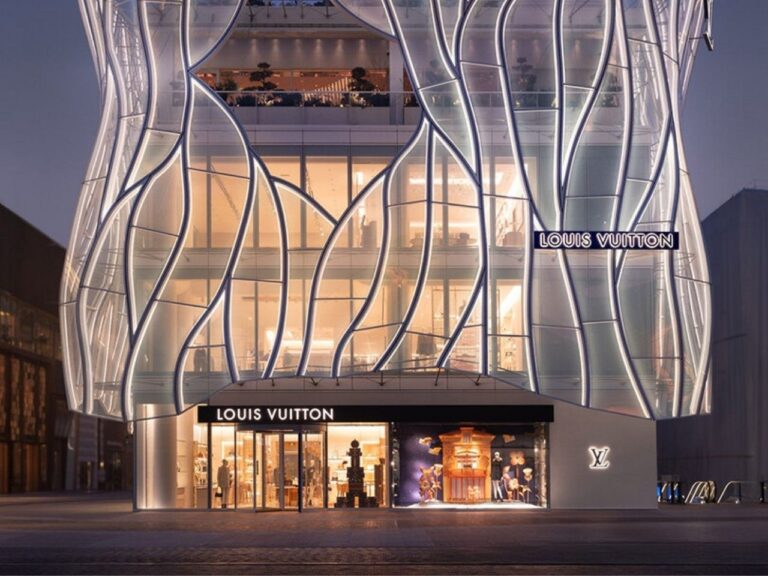

When the Building Becomes the Logo

As the project progressed, an unplanned transformation occurred: the architectural mass itself became a visual identity. The triangular form, which began as a geometric abstraction, evolved into a recognizable silhouette without any additional elements. Here, the building no longer required a traditional logo because the architecture itself fulfilled that role.

This transformation reflects a design philosophy that sees architecture, when clear and balanced, as capable of representing an institution without graphic mediation.

Working Under Diplomatic Sensitivity

Designing a diplomatic building is unlike any other project. Every decision passes through layers of coordination with sovereign authorities, municipal systems, security requirements, and international protocols. In this project, the challenge was not only technical but also procedural and diplomatic.

The development process involved multiple meetings, continuous reviews, and adjustments dictated by considerations not visible in drawings. This type of project requires an architect capable of managing dialogue as adeptly as design itself.

Architecture that Thinks Before It Is Built

Today, with construction progressing, the project is no longer just an idea on paper. The initial sketches, mathematical studies, and sustainability models are all gradually taking physical form. Yet, the value of the project lies not only in its final shape but in the process that led it there.

The Indonesian Consulate in Jeddah presents a model of quiet diplomatic architecture, one that does not shout symbolism nor abandons identity. Architecture that sees thinking as part of building, and building as an extension of the relationships between nations.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

Despite the clear conceptual maturity of the project, this type of architecture, based on high abstraction and a rigorous analytical approach, opens the door to legitimate questions. Relying on a deep geometric and mathematical logic may, in the eyes of some users or visitors, limit the ability to read the building emotionally or perceive its cultural references without prior knowledge of the design context. This is not a flaw so much as a conscious choice, but it positions the project within a category of architecture that requires a reader as much as it accommodates a user.

Moreover, transforming cultural elements into generative systems, despite its design intelligence, may spark discussions about the acceptable limits of abstraction in diplomatic projects, where symbolism is sometimes expected to play a more explicit role in building collective memory. On the other hand, the project is credited for avoiding superficiality and direct representation, offering a model that can inform similar projects seeking to express identity through methodology rather than form.

From a professional perspective, the project provides an important lesson in managing complexity, cultural, environmental, and procedural. It also opens the door to a broader discussion about the future of diplomatic architecture in the region and its ability to evolve from closed symbolic buildings into architectural systems conscious of their context, even if this comes at the expense of immediate readability or direct emotional response.