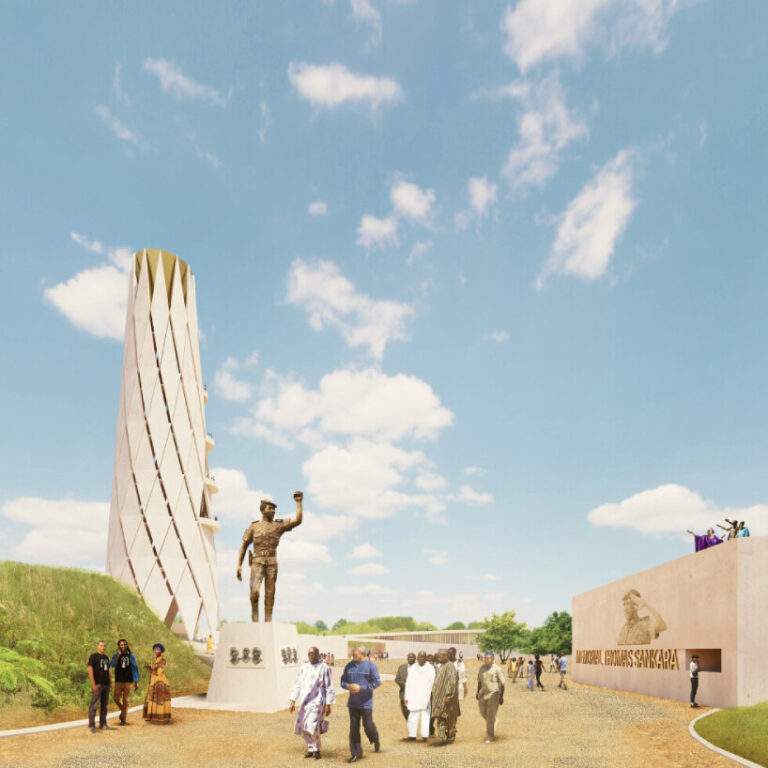

Living on Groundwater: Redefining the Relationship Between Housing and Groundwater Management

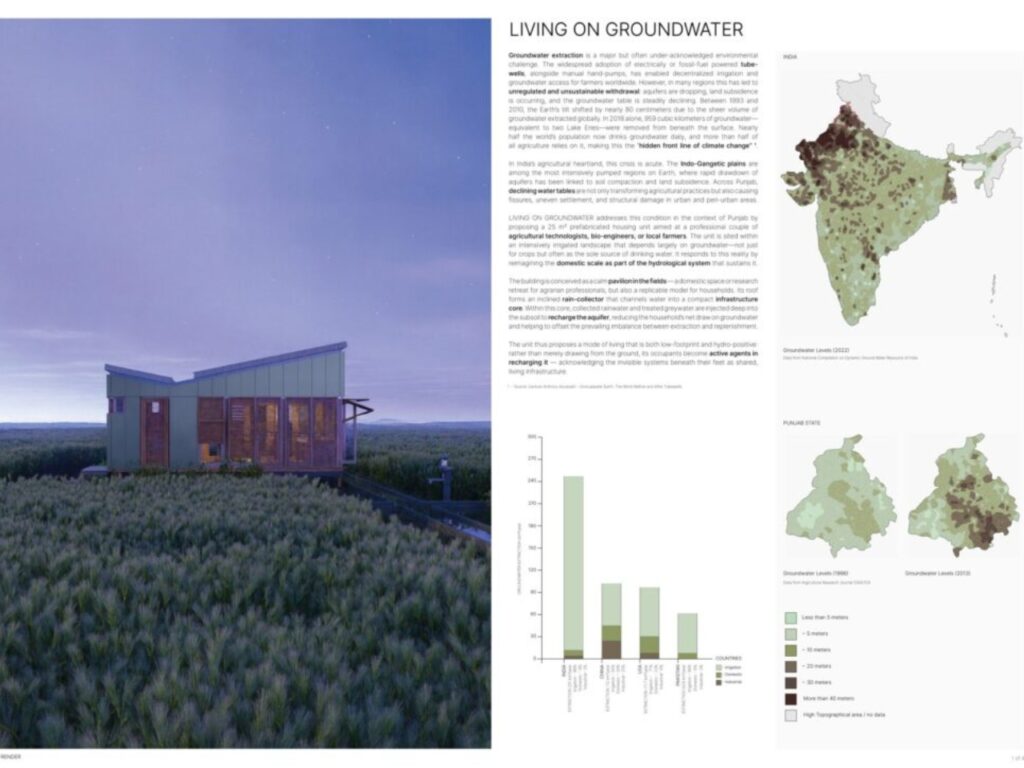

The Global Groundwater Crisis

If you live in an area where drinking water or groundwater is not a major concern, consider yourself lucky. However, there are many regions around the world where groundwater poses a real challenge, significantly affecting the quality of life. For instance, the state of Punjab in India is currently facing one of the most severe groundwater depletion crises due to intensive agricultural practices.

Innovative Approaches to Managing Natural Resources

In response, innovative design solutions have emerged to adapt to this crisis. One example is the “Living on Groundwater” project, designed by architects Alexa Milovich and Matthew W. Wilde from New York. Despite its small footprint of just 25 square meters, the house embodies a practical approach to addressing local environmental challenges.

The Role of Design in Groundwater Recharge

Through this project, the goal extends beyond merely providing living space; it also actively contributes to improving the surrounding environmental conditions. The architecture allows residents to directly participate in groundwater recharge, turning them into active stewards of natural resources rather than mere consumers.

Innovative Water Management Technologies

This innovative small house features an integrated rainwater harvesting system, alongside greywater recycling systems. It also includes an on-site injection well that returns treated water directly to the groundwater reservoir.

A Model of Water-Positive Housing

The house represents a unique example of water-positive housing, with a low carbon footprint and the ability to return more water to the environment than it consumes. Through these features, the project demonstrates how housing can be part of environmental solutions rather than contributing to worsening problems.

Redefining the Concept of Small Homes

This model goes beyond the traditional notion of a home as merely a living space, becoming an active environmental infrastructure aimed at restoring local ecological conditions. It can be envisioned as a home whose presence is not limited to the land it occupies, but actively participates in treating and enhancing its natural resources. For related innovative projects, see our Projects section.

Design in Harmony with the Environment

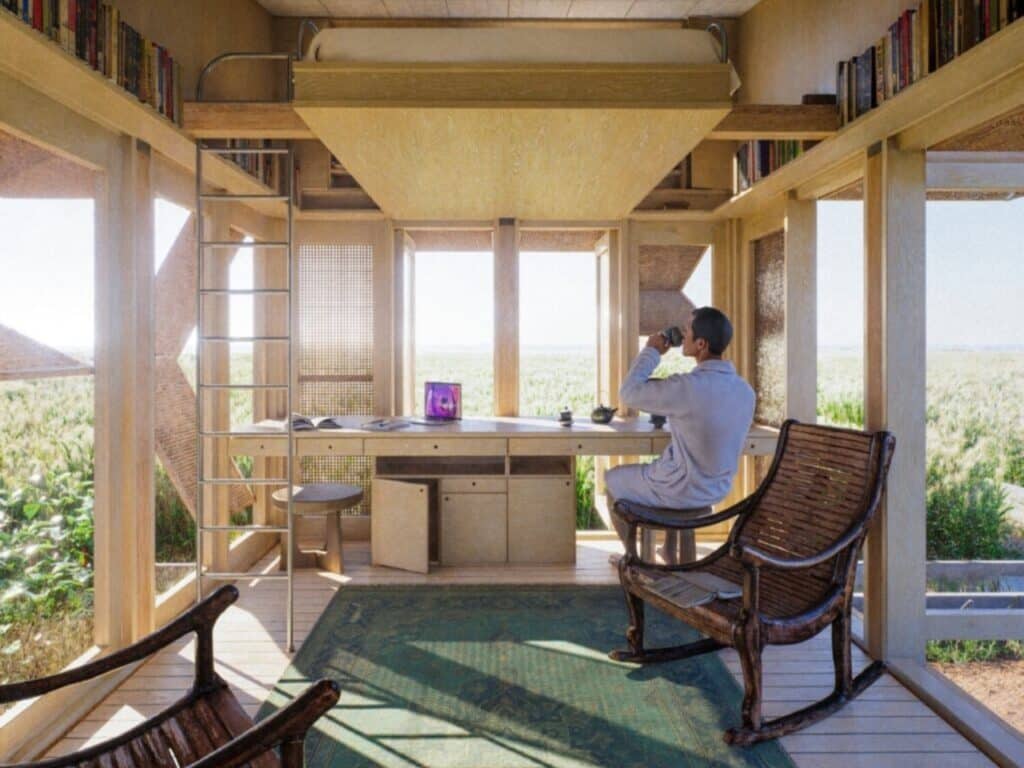

In terms of design, the house features a refined rural aesthetic that seamlessly blends with the agricultural landscape of Punjab. This approach demonstrates how architecture can contribute to enhancing the harmony between built structures and the surrounding nature.

Elevated Structure to Protect the Soil

The house sits on a lightly elevated wooden frame above the fields, minimizing ground disturbance. This elevation allows water flow, air movement, and plant growth underneath to occur freely. As a result, the soil below can “breathe” and function naturally, rather than being compacted or sealed as with conventional foundations. More examples of buildings using elevated foundations can be explored in our archive.

Sustainable Design

This approach reflects a design philosophy centered on sustainability, balancing human use of the land with the preservation of ecosystem functions, making the building an active participant in supporting the environment rather than a burden on it.

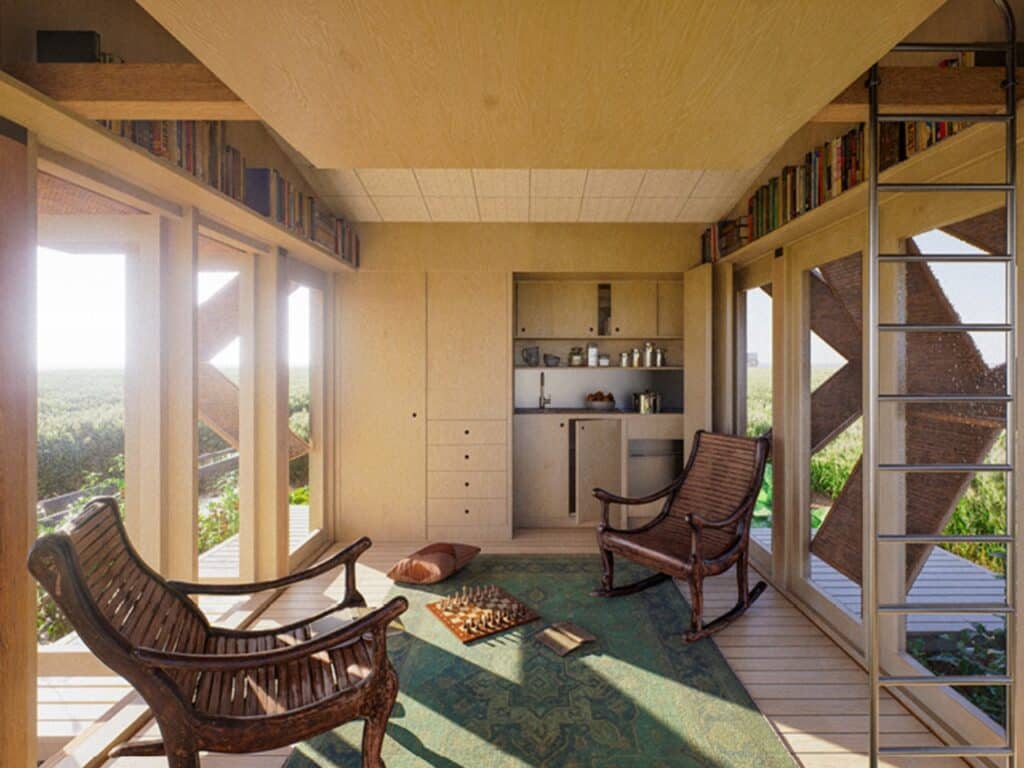

An Environmentally Responsive Facade

The house features a permeable facade that allows natural light and surrounding views to become part of its interior atmosphere. This interior design approach reflects the building’s ability to interact with the environment rather than isolate itself from it.

Responsive to Seasons and Weather

The facade adapts to seasonal changes while maintaining visual connection with the surrounding landscape. In hot summers, it provides shade and natural ventilation, while in colder months, it efficiently captures warmth and light.

Balancing Comfort and Sustainability

Through this approach, the design allows residents to modulate their relationship with the outdoors and the surrounding environment according to weather and season, enhancing personal comfort while making efficient use of natural resources. For more sustainable solutions, visit our Building Materials section.

Practical and Flexible Design

The sleeping area is designed as a loft, allowing the ground floor to remain an open space for living and working. This approach reflects the efficient use of every inch of the compact 25-square-meter (269-square-foot) house.

Adaptable Furniture

Inside the house, modular cabinets and convertible work surfaces are integrated, ensuring that the furniture adapts to the user’s needs rather than imposing a fixed way of living. This provides the flexibility necessary to maximize the small space without compromising comfort or functionality.

Prefabricated and Replicable Design

The house’s walls and roof are prefabricated, allowing the design to be replicated in different rural contexts without losing its functionality or environmental benefits. This approach demonstrates the potential for sustainable expansion and the efficient dissemination of architectural housing solutions across multiple regions.

Global Recognition for Sustainable Design

The Living on Groundwater project has received international acclaim for its design and environmental quality, earning first place in the MICROHOME #10 competition results, organized by Buildner and sponsored by Kingspan.

Integrating Technological Innovation with Sustainability

The international jury praised the project’s exceptional ability to combine technical building systems with the local environment, as well as its approach to addressing groundwater challenges.

The House as an Active Environmental Agent

This recognition demonstrates how a small house can go beyond being a low-impact shelter to become an active contributor to environmental restoration and the sustainable management of natural resources. For related research, see our dedicated section.

Field Research as the Basis for Innovation

This project stands out as the result of meticulous research on the history of agriculture in India, conducted through a seminar and field study in Punjab at Yale University. This approach highlights the importance of a deep understanding of the local context before proposing any design solutions.

Design Responsive to Local Needs

The designers did not limit their work to providing generic, ready-made solutions; instead, they studied the land and understood its unique challenges. As a result, they developed a design that genuinely responds to the specific needs of the region, enhancing the house’s ability to adapt to the environment and achieve true sustainability.

Small-Scale Architecture as a Sustainable Solution

Amid increasing pressures on housing due to climate instability, rising construction costs, and growing demographic needs, the Living on Groundwater project offers a promising model. The project demonstrates how small-scale architecture can be both efficient and aesthetically pleasing.

Combining Efficiency with Aesthetics

The design highlights the ability of compact spaces to provide comfort without feeling cramped, accommodate modern elements without losing warmth, and maintain resource sustainability without compromising quality of life.

Design in Harmony with Nature

The project emphasizes that the most effective solutions often stem from a deep understanding of the problem and designing homes that harmonize with nature rather than conflict with it. This approach positions architecture as an active agent in supporting the environment and enhancing quality of life.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

The Living on Groundwater project can be seen as a model demonstrating how small-scale architecture can be integrated with water resource management, highlighting the potential of prefabricated design to achieve partial sustainability. On a positive note, the project allows users to interact with the environment and share resources in a considered way, while also reflecting the idea of incorporating simple technological solutions within a compact architectural context.

However, certain cautionary considerations remain when attempting to generalize this model or apply it on a larger scale. First, focusing on small homes may not meet all diverse housing needs, particularly in rural areas that require larger spaces or multifunctional uses. Second, the success of the ecological and technical systems relies heavily on ongoing maintenance and prior knowledge of environmental practices, which may pose challenges for ordinary residents or in different contexts. Third, while the project demonstrates adaptability to the local environment in Punjab, climatic conditions, soil, or water resources in other regions may differ, making the direct replication of the same model less effective or more complex.

Overall, the project serves as an important reference for studying the integration of architecture with environmental water management. It provides opportunities for innovative thinking, yet emphasizes the continued need for a precise understanding of the local context before considering it as a universal model. For more related archive studies, visit our collection.