Liberation Museum of Manisa: Architectural Design Integrating Historical Narrative and Spatial Experience

Liberation Museum of Manisa: A Space of Memory and History

The Liberation Museum of Manisa (MKM) was designed as a living space of memory, aiming to present a historical narrative of the civilian popular movement that developed in the Manisa region independently of the central authority between 1918 and 1923.

Integrating History into Architectural Design

The design reflects the city’s suffering and resilience by merging the traces of surviving load-bearing stone and brick structures after the fire with Manisa’s deep-rooted local brick tradition, whose origins date back to ancient periods. This integration grants the museum a distinctive character that bridges authenticity and contemporaneity.

A Sequential Experience Within the Museum

The fourteen independent chambers of the museum, constructed entirely using the load-bearing wall technique, are arranged to offer visitors a series of successive historical stations. This spatial organization enables a gradual and immersive experience, guiding visitors through different chapters of the city’s history and fostering a deeper understanding of the historical period Manisa endured.

Expressing Historical Transformations

The sequences within the museum represent significant historical turning points, where the distinctive emotional state of each space is emphasized. This approach allows visitors to comprehend events not in an abstract manner, but through a tangible, sensory experience.

Spatial Tension and Architecture

Architectural elements such as brick arches, vaults, domes, and tent-like coverings contribute to the creation of diverse spatial contrasts, including:

- Shadow versus light

- Constriction versus openness

- Descent versus ascent

An Integrated Sensory Experience

The architectural details of each chamber reflect the nature of its historical context, enabling visitors to experience events not only through reading or observation, but through a physical sensation of space. In this way, the museum becomes a comprehensive educational experience that combines historical knowledge with spatial interaction.

Construction Phases and Brick Techniques

The construction of the museum began with the creation of a concrete base for each chamber, forming a solid foundation capable of supporting the structure. Subsequently, bricks of varying dimensions were used in the construction of the walls, allowing for diversity in form and texture across the different spaces.

The Use of Wooden Formwork

In the following phase, wooden formwork was prepared to support the walls during construction. This formwork was essential for accurately shaping chambers with arches, tent-like forms, or domes, and for ensuring structural stability throughout the building process.

Revealing the Rhythm of Brickwork

In the final stage, once the formwork was removed, the rhythm of the brickwork became clearly visible on the interior surfaces, imparting a distinctive and unexpected artistic quality to the structure. This approach not only highlights the technical aspects of construction, but also reflects a strong attention to aesthetic and architectural detail within each chamber.

Descending into History

Visitors descend into this semi-underground narrative space via a three-branch ramp, marking the beginning of a cognitive journey through the modern history of Manisa. This design evokes a sense of movement between different temporal layers, transforming the act of walking into a gradual and sensory introduction to the understanding of historical events.

The Main Hall: The Heart of the Museum

The main hall at the entrance was designed as an undefined semi-elliptical space, characterized by brick arches and concrete vault slabs that evoke the image of the belly of a whale. This central space functions as a grand foyer connecting the various areas of the museum, offering a strong sense of immersion before transitioning into the other chambers.

Narrating Events Through the Nine Chambers

From this hall, the sequence of events in Manisa is narrated, beginning with the context of the First World War, passing through the great fire, and culminating in the reconstruction, across nine diverse narrative chambers. These spaces vary in the intensity of their sensory and emotional impact, allowing visitors to experience each historical phase in a direct and embodied manner, both through spatial perception and psychological engagement with the history on display.

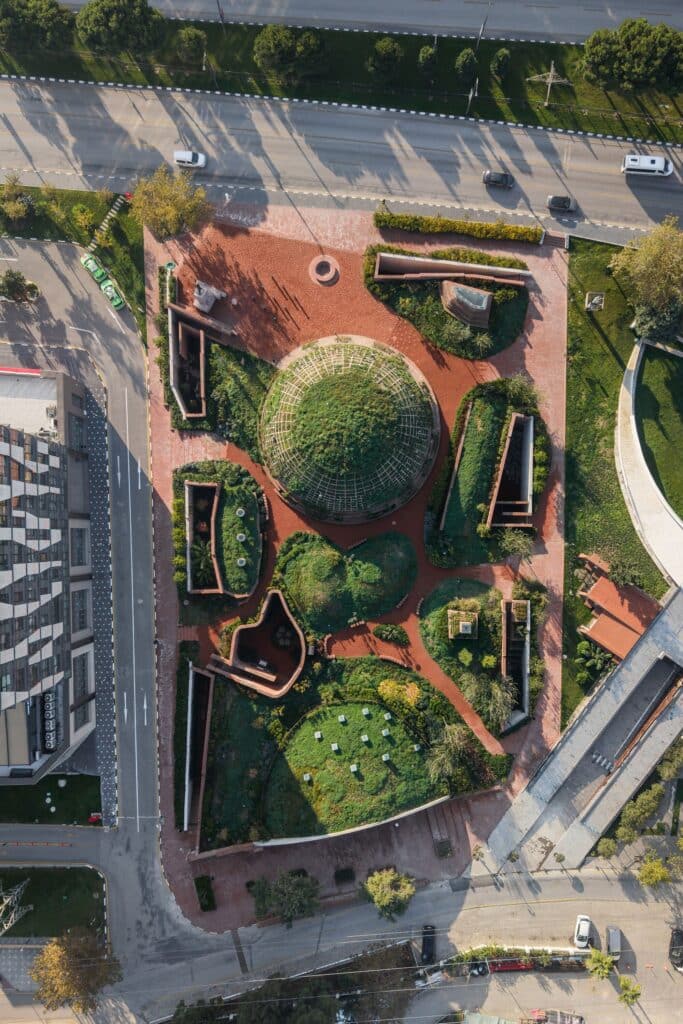

The Upper Level: A Public Garden Above History

The upper level of the building was constructed entirely using load-bearing brick, forming a public space designed as a garden. This garden offers visitors and passersby the opportunity to move freely and enjoy a green environment, fostering a sense of comfort and relaxation.

A Subtle Interaction with History

Residents of the city or visitors to the garden may not be consciously aware of the deep historical narrative unfolding beneath their feet. However, the mounds and barriers shaped by the museum’s interior spaces within the garden create an indirect and subtle experience of engagement with the museum. These raised forms transform the garden into more than a simple public space, turning it into a multilayered environment with its own internal sections, thereby reinforcing awareness of the relationship between place and historical memory.

The Main Objective of the Museum

The Manisa Liberation Museum (MKM) aims to convey the profound trauma and the series of resurgence events experienced by the city in the recent past to visitors and citizens of all ages. The museum offers a comprehensive educational experience, combining historical narrative and spatial design to enable a deeper understanding of the events and their impact on the local community.

Diverse Narrative Tools

Various architectural and spatial devices were employed to achieve this goal, including:

- Chambers focused on historical information

- Highly sensitive spaces that convey a sense of place and time

- Narratives in which the character of the architectural composition is prominently highlighted

The Museum as a Multi-Layered Architectural Insertion

The MKM can be described as a multi-layered, semi-archaic architectural insertion that seeks to forge connections between the past and the present. It leaves a lasting impression that links visitors to both place and time, while also pointing toward future perspectives for understanding the relationship between collective memory and architecture.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

The Manisa Liberation Museum demonstrates a clear ability to employ architecture as a medium for historical storytelling. The project successfully transforms the chronological sequence of events into a spatial experience that visitors can comprehend through movement and sensory perception, rather than through informational display alone. The use of load-bearing brick and traditional construction techniques provides material consistency with the local memory, while creating spaces with a tangible identity, particularly in the narrative chambers that reflect historical transformations through spatial and light contrasts.

On the other hand, this approach, heavily reliant on sensory experience, raises questions about the balance between emotional impact and cognitive clarity. The intensification of spatial symbolism and the variety of emotional states may sometimes obscure historical understanding for certain visitors, especially those less familiar with Manisa’s historical context. Moreover, relying on sequential movement within enclosed, semi-underground spaces can limit the flexibility of the experience, making the temporal progression feel imposed rather than freely discovered.

From an architectural standpoint, the integration of the upper level as a public garden is commendable. Yet, this near-complete separation between the public space and the internal historical narrative may reduce opportunities for conscious engagement with the museum’s content, leaving the historical presence unperceived except by those who enter the building. Additionally, the heavy focus on brick as the dominant element, despite its expressive power, may limit the long-term material reading and interpretation of the project.

Nevertheless, the Manisa Liberation Museum offers a valuable model for memorial architectural projects, particularly in its use of the building itself as a narrative tool rather than merely a vessel for display. At the same time, it highlights the importance of achieving a finer balance between sensory experience, historical clarity, and user interaction, considerations that are essential for any project aiming to translate collective memory into an intelligible and enduring architectural space.