The Veranda: A Disappearing Threshold Space in India

The Veranda: A Disappearing Threshold Space in India

An ancient Indian folktale narrates the story of a demigod, Hiranyakashipu, who was granted a boon of indestructibility. He wished for his death to never be brought about by any weapon, human or animal, not at day or night, and neither inside nor outside his residence. To cease his wrathful ways, Lord Vishnu took the form of a half-human-half-animal to slay the demigod at twilight at the threshold of his house.

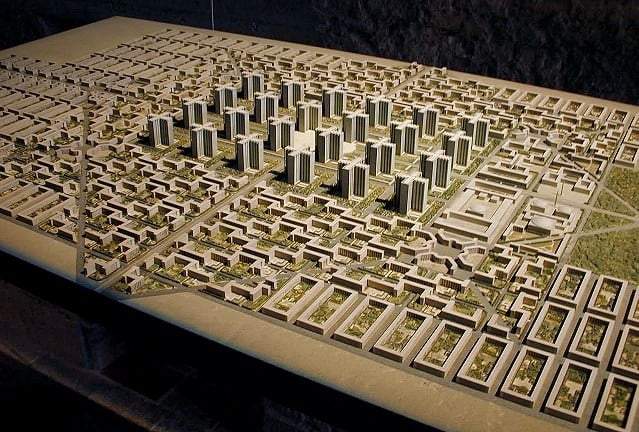

Threshold architectural spaces have always held deep cultural meaning to the people of India. In-between spaces are found in the midst of daily activities as courtyards, stairways, and verandas. The entrance to the house is revered by Indians of all social backgrounds. Throughout the country’s varied landscape, transitional entry spaces are flanked by distinctive front verandas that merge the street with the house.

+ 6

+ 6

In India, the vernacular entrance veranda emerged out of a need for outdoor space that would be cooler than the indoors. To avoid the heat, people would spend most of their day in this space. The in-between space hosted activities from early morning chores to evening lessons for children of the community. Liminal spaces in the urban environment are activated by the buzz of daily life.

Related Article

Interstitial Spaces and Public Life, the Overlooked Interventions that Weave our Built Environment

Lining the street edge with a permeable thickness, the veranda mediated the public realm with the private home. Constant activity on the street would pour onto the space and vice versa. The threshold space was an activator of public activity, keeping streets alive at an arm’s length from the sheltered interiors. The sounds and smells from the constant movement of people were shared between the public and semi-public areas. Pritzker laureate B V Doshi describes verandas as “the meeting place between the sacred and profane; the house and the street”.

The mysticism of the in-between is a recurring theme in Indian philosophy. The veranda receives special attention every morning through worship and decoration, especially during festivities. The threshold was also a space to extend hospitality, one where neighbors and passers-by could stop for spontaneous conversation. The space formed an integral part of traditional houses, celebrating the culture of generosity and community. Legally, the veranda belonged to the owner of the dwelling. Socially, it was seen as an extension of the street, a public space for the community to work, gather, and gossip.

With varying climates, the veranda took on different forms and sizes throughout the country while maintaining the same function. Typologies generally denoted the transition of the street to the house with a change in material and elevation. “The thinnai of South Indian colonies, the otla of North Indian pol residences, and the Portuguese-inspired balcao vary in ornamentation and socio-cultural influences” shares Lester Silveira of The Balcao. Verandas were profusely decorated by residents to express their cultural values.

The transitional space served as a vital bridge between private and public life. With urbanization, there has been a widening of the gap between public and private life and along with it, the disappearance of the veranda. Notions about privacy and socializing have changed over the last few generations. In parallel, new forms of habitation have emerged in cities, dictated more by economics than socio-cultural patterns.

The advent of cities and modernized forms of construction has pushed vernacular Indian architecture into history. “Local architecture takes on a more universal language and material palette, paying lesser attention to threshold spaces”, Silveira states. Apartment and house designs maximize on indoor living, leaving outdoor spaces as an afterthought. While the front veranda shrunk, large patios and balconies grew at the back of the house, offering a more private outdoor experience. In buildings where the veranda has been counterfeited, they are cut off from the street by compound walls and gates.

Technology has also fueled the gradual decline of architecture’s ability to engage with the public realm. Air-conditioners, television, and the internet have created more comfortable indoors, making outdoor living spaces redundant. Alternative architectural shading devices challenged the veranda’s ability to cool spaces. Streets are no longer filled with the chatter of pedestrians and hawkers. The noise from vehicular traffic keeps dwellings turned away from the street. Being visually cut-off, buildings are engaging lesser with the urban fabric than ever before.

A modern rendition of the veranda is the entry foyer, a closed-off space one first walks into that is more secure for the deliveries and transactional conversations of today. Indian villages still hold onto traditional ways of life and the architecture that supports them, but cities respond to privatized lifestyles. One may occasionally find a person enjoying a newspaper in their apartment corridor or shouting to a vendor passing through the street. The bustle of interlinked spaces, however, is rare to come across.

The loss of transition space between the private and public sphere has depleted the sense of community in shared environments. Structures that scoop out pockets for organic activity have been replaced by introverted buildings surrounded by mechanical public spaces. Architects may use the veranda as memorabilia – from a time of blurred boundaries and togetherness – but the space is devoid of its intended character. Is the charm of the veranda lost forever?

Built environments echo the cultural and practical needs of fleeting generations. While looking upon the past with nostalgia, clues to better cities and communities reveal themselves. The example of the veranda highlights architecture as more dynamic, activating spaces around it in humane scales, and around daily activity. Buildings that externally relate to each other automatically produce active in-between zones. Transition spaces can regulate the pace between busy public areas and slower dwellings, smoothly translating one into the other.

Simply bringing back the veranda cannot patch the fork between public and private life. What architects can take forward is not a transitional space, but a transitional place that can nurture community, invite lingering, and hold the character of the mystical in-between.

Related Article

Interstitial Spaces and Public Life, the Overlooked Interventions that Weave our Built Environment