Wangun Amphitheatre by Equity Office

Introduction

The Wangun Amphitheatre, designed by Australian firm Equity Office in southeastern Victoria, is a cultural performance space developed for and with the Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation (GLaWAC). Situated in the bushland of Kalimna West, this 100-seat amphitheatre is more than a performance venue—it’s an architectural gesture of cultural respect, community partnership, and ecological responsiveness.

Follow all bold ideas, trends, and updates from the world of architectural content on ArchUp.

Architectural Intent and Cultural Co-creation by Equity Office

What sets this project apart is its foundation in co-creation. The design process wasn’t architect-led in isolation; instead, it was deeply collaborative, involving GLaWAC and architecture students from Monash University. This model of participatory design moves away from traditional top-down architectural practice, creating a space that genuinely reflects Indigenous values and aspirations.

The name “Wangun” (meaning boomerang in the Gunaikurnai language) is more than symbolic. The boomerang metaphor—something that returns—parallels the community’s hope that visitors return to continue learning and sharing in Gunaikurnai knowledge and storytelling.

However, this metaphor is also where the project risks veering into abstraction. While the concept is powerful, there is limited evidence of how the space itself facilitates sustained engagement beyond singular visits or symbolic representation. The challenge for this kind of architecture is translating cultural narrative into physical forms that foster continuous, living interaction—not just static reverence.

Materiality and Environmental Strategy

The choice of materials is notable for both cultural and environmental reasons. Local, non-toxic resources such as rammed earth and spotted gum were prioritized, reflecting an Indigenous connection to land. These materials are low-impact and regionally relevant.

However, the reality of bushfire risk in southeastern Australia forced a compromise. The core structure was built from concrete for seating and steel framing for the canopy—materials chosen for their non-combustibility rather than vernacular warmth or tactile appeal. While pragmatic, this introduces a clear material tension between ecological ideals and safety requirements.

This is not a flaw, but it highlights the difficult balancing act contemporary architecture must perform in fire-prone regions—especially when aiming to remain culturally rooted.

Canopy Design and Symbolism

The most visually prominent element is the series of steel-framed fabric canopies. These aren’t random shapes—they represent Gunaikurnai clan shields, with a larger boomerang-shaped canopy over the stage. The symbolic intent is admirable and even poetic, and the choice of PTFE fabric allows for dynamic visual experiences: casting tree shadows by day and serving as a projection surface by night.

Still, there’s a question of performance versus permanence. Will the visual storytelling of the shields be sustained over time through the proposed projection art? Or will it fade into decorative abstraction if not actively maintained and curated? Symbolism in architecture requires stewardship—without it, meaning risks being reduced to form.

More on ArchUp:

Landscape Integration and Masterplanning

The surrounding landscape emphasizes indigenous vegetation, part of a broader masterplan including a garden and a cafe. This landscape-led approach is critical—it avoids treating the amphitheatre as a standalone object and instead embeds it in a living ecological and cultural system.

Even more significantly, the success of this phase prompted GLaWAC to initiate a zoning change to Special Use Zone, allowing for further culturally expressive development. This is perhaps the strongest legacy of the project—not the structure itself, but the process it established: participatory, regenerative, and rights-based.

Conclusion: A Model or a Moment? Wangun Amphitheatre

The Wangun Amphitheatre is a compelling model of how architecture can serve Indigenous communities without appropriation. Its success lies not just in its form or materials, but in the co-creative methodology, which could inform similar efforts across Australia and beyond.

Yet, it also illustrates the fragility of such models. Cultural symbolism requires long-term engagement, maintenance, and programming. Otherwise, the space risks becoming an empty gesture. If continuously activated and supported, Wangun can indeed return—as its name suggests—again and again, as a meaningful cultural encounter.

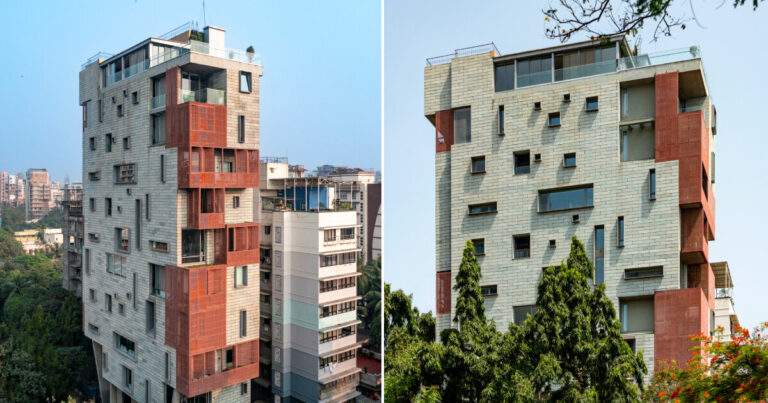

Photos: Equity Office