Is Architecture Biased?

Why Some Cities Become Emotional Destinations While Others Remain Silent

There is a sentence people repeat without thinking about its implications: “Paris is poetic.”

Rome is romantic. Vienna is musical. New York is cinematic. These descriptions are not architectural analyses. They are emotional shortcuts, built over decades, sometimes centuries, of cultural repetition. Cities become brands not because of a single building, but because the world collectively agreed to remember them in a certain way.

What is striking is not that these cities deserve their reputation, but that others rarely receive one at all.

Few people say they dream of visiting an opera house in Shanghai, or a cultural district in Tokyo, even though both cities host architectural works of extraordinary ambition and technical mastery. The absence of desire is not proportional to the absence of quality. It is proportional to the absence of narrative.

This is where the question of architectural bias begins.

Over the past two decades, the global architectural scene has shifted eastward in terms of production. China, Japan, South Korea, and parts of the Middle East have become laboratories for scale, experimentation, and speed. Major global architects maintain offices, portfolios, and landmark projects across Asia. Entire skylines have been redrawn within a single generation. Yet the emotional gravity of architecture, the kind that pulls people across continents for a “feeling,” remains overwhelmingly Western.

The question is not whether Eastern architecture is good enough. It clearly is. The question is why it does not echo.

Part of the answer lies in how architectural meaning is constructed. Europe did not simply build buildings; it built stories around them. Cafés, squares, museums, and opera houses were woven into literature, painting, cinema, and everyday ritual. Architecture became a stage for memory. A person does not travel to Paris to see a façade. They travel to inhabit a story they already know.

This is not accidental. It is the result of centuries of cultural reinforcement. Western cities benefited from early global dissemination through colonial networks, publishing, education, and later mass media. Their architecture was exported as reference, studied as canon, and framed as universal. This canonization created a feedback loop: the more Western architecture was discussed, the more it was desired; the more it was desired, the more it was discussed.

By contrast, much of contemporary Eastern architecture emerged within compressed timeframes. Cities expanded rapidly, often faster than cultural digestion could occur. Buildings appeared before rituals formed around them. Icons rose without narratives settling in. The result is a landscape of impressive objects that struggle to become emotional destinations.

This difference is not about aesthetics. It is about temporal depth.

Consider Japan. Few countries possess such refined architectural intelligence, from traditional timber construction to contemporary minimalism. Yet even there, architecture is often internalized rather than broadcast. It is experienced locally, quietly, without the performative desire to brand itself for external consumption. This restraint produces depth, but not always visibility.

“Between 2000 and 2023, more than 70 percent of globally awarded ‘iconic’ architectural projects were commissioned in Western or Western-aligned economies, despite Asia and the Middle East accounting for over 60 percent of new urban population growth. Academic studies also show that over 80 percent of architectural theory cited in leading English-language journals originates from fewer than ten Western institutions. This imbalance reveals that architectural bias is not merely aesthetic, but structural, embedded in funding flows, publication systems, and the mechanisms that define what the profession collectively recognizes as ‘advanced’ architecture.”

China presents another paradox. Architectural output is immense, technically advanced, and often daring. Entire districts showcase what could be described as an architectural explosion. Yet when everything is exceptional, nothing becomes singular. The background noise overwhelms the signal. The eye adapts too quickly. Novelty loses its narrative power.

This raises an uncomfortable question: does architecture need scarcity to become meaningful?

Western cities benefited from slowness. Buildings accumulated significance over time. Their imperfections aged into charm. Eastern cities often leapfrog stages, moving from absence to abundance too quickly for mythology to form. The architecture arrives before longing.

Language also plays a role. Architectural discourse remains dominated by Western institutions, publications, and critical frameworks. Even when Eastern projects are celebrated, they are often explained through Western lenses. The validation still flows from one direction. This asymmetry reinforces perception. If architecture is not narrated in a language the global audience recognizes, it struggles to resonate emotionally.

Digital platforms complicate this further. Algorithms reward repetition and familiarity. Western architectural imagery circulates because it has always circulated. Eastern architecture, despite its quality, enters the stream as anomaly rather than reference. It becomes content, not context.

This is why a striking building in the East may feel visually impressive but emotionally distant. The viewer sees it, admires it, scrolls past it. There is no inherited desire attached to it. No accumulated memory. No cinematic echo.

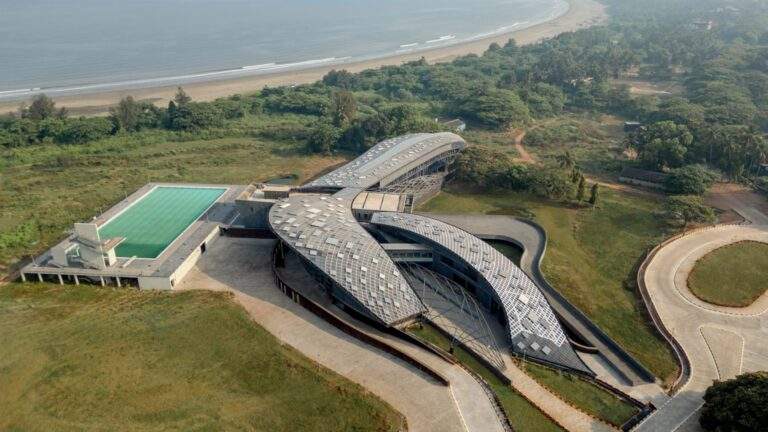

The example of landmark projects by global architects in Asia illustrates this tension. A single iconic building, no matter how refined, cannot manufacture cultural gravity on its own. When surrounded by dozens of equally ambitious structures, it becomes part of a field rather than a focal point. Contrast this with European cities, where architectural density is often historical rather than competitive. One building dominates because others recede.

This does not mean the West will maintain its architectural aura indefinitely. Cultural dominance is not permanent. As global attention fragments, and as younger generations consume space differently, emotional hierarchies may shift. Desire may detach from old capitals and reattach to new ones, but only if narratives catch up with construction.

Architecture, ultimately, is not judged by form alone. It is judged by how deeply it embeds itself into collective imagination. Until Eastern cities cultivate slower, layered, and self-authored narratives around their architecture, their buildings may remain visually admired but emotionally silent.

The question, then, is not whether architectural bias exists. It clearly does. The deeper question is whether the East will attempt to correct it by speaking louder, or by learning how to be remembered.

And perhaps the most uncomfortable realization of all is this: architecture does not become universal by being excellent. It becomes universal by being believed in.

The coming decades will reveal whether the glow surrounding Western architecture is a permanent inheritance, or simply a long echo waiting to fade.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

This article offers a sharp cultural reading of the architectural imagination, contrasting the romanticism assigned to Western cities like Paris or Rome with the global neglect of Eastern architectural icons. The structure moves from anecdotal observation to systemic critique, using the emotional branding of architecture—coffee in Milan, sunsets in Santorini—as a lens to expose deeper biases. Architecturally, it rightly questions why masterpieces in Shanghai or Tokyo rarely become pilgrimage sites, despite matching or surpassing Western counterparts in complexity and craft. Yet it could further probe how colonial legacies and media gatekeeping have shaped global architectural taste. The piece echoes themes seen in “Architecture and Identity” and “American Decoration”, pushing the reader to reassess what and who defines architectural value. A quietly urgent call to rebalance the compass of desire in our built world.