Does Architecture Mirror the Soul of Its People?

Picture yourself wandering through the narrow streets of an ancient city, gazing at the buildings their arches, patterns, and weathered facades. Suddenly, it hits you: these structures feel like they belong to the people who live here. Not just in their style or function, but in some deeper way, as if the buildings carry a piece of the community’s essence. A fascinating new study takes this fleeting thought and spins it into a question that’s both simple and profound: does architecture reflect the very identity of the people who create it?

we build what we are

Archigenetics

This research, built on years of observation and insight, explores a surprising connection between our physical features, our traditional clothing, and the cities and homes we design. It asks something we’ve all wondered at some point: do we build based on what we love, or based on who we are?

The Spark of an Idea

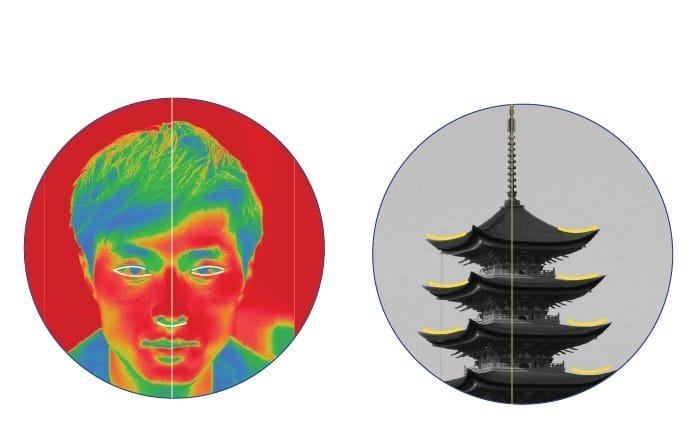

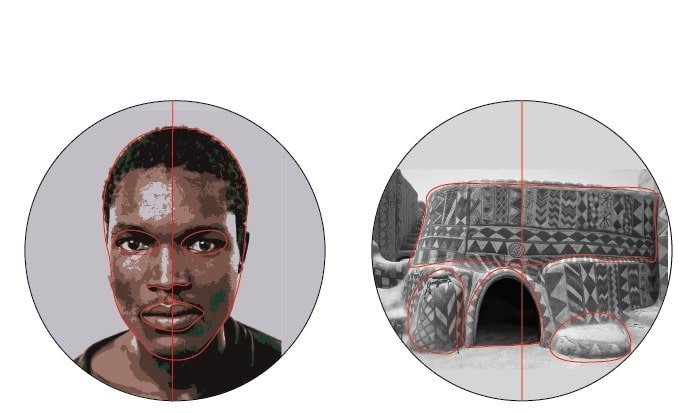

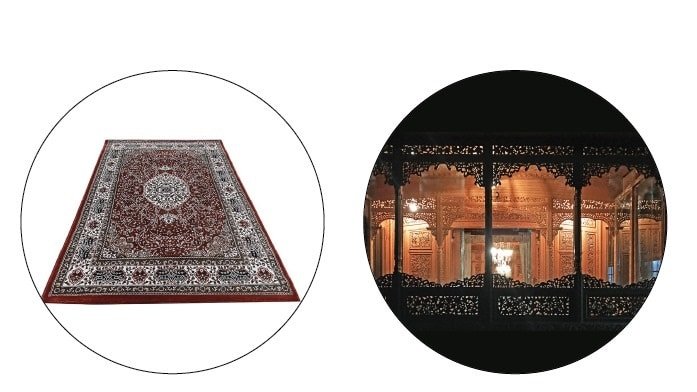

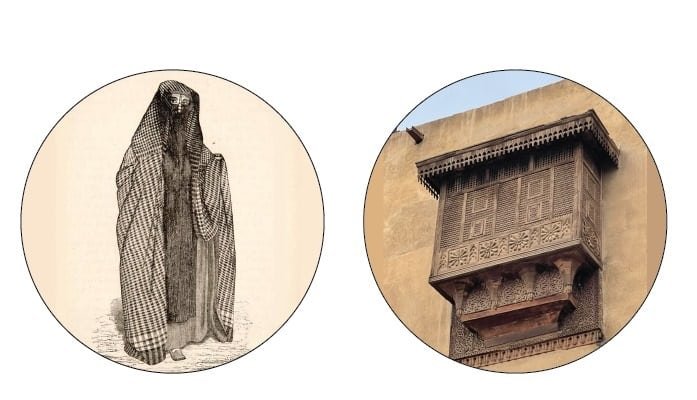

It all began with a quiet observation. If you’ve ever strolled through a place like Kyoto in Japan or Fez in Morocco, you might’ve noticed that the buildings seem to fit the people. In Japan, homes are serene and minimal, with clean lines and a sense of balance that feels almost like an extension of the elegant kimono or the calm, measured gestures of daily life. In Morocco, the vibrant, intricate tilework on walls echoes the colorful patterns of a traditional kaftan, full of energy and rhythm. Even in ancient Greece, those perfectly proportioned marble columns seem to celebrate the same idealized forms you see in their sculptures.

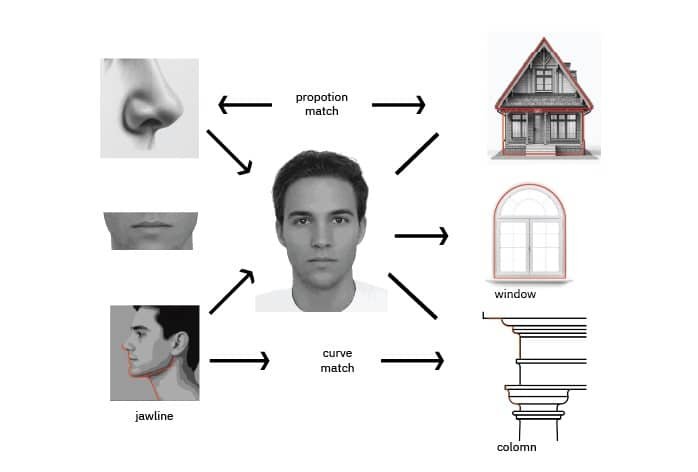

The researchers decided to dig into this idea. They used visual analysis tools to compare the shapes of human faces—think cheekbone angles or the curve of a jaw with the architectural elements like arches, windows, and decorative patterns. Could there be a link? What they found was startling: in many cases, there’s a subtle thread tying a community’s physical traits to the way they build.

Beyond the Buildings

The study didn’t stop at architecture. It stretched further, looking at traditional clothing, the way people move, and even how cities are laid out. Imagine the open, airy courtyards of Moroccan homes, where light and movement flow freely don’t they feel a bit like the expressive, fluid steps of a traditional dance? Or consider the compact, efficient layouts of Japanese cities, mirroring the disciplined, purposeful movements of their residents.

These connections aren’t just coincidences. The research suggests there’s an “aesthetic code” weaving together our features, our clothes, and the spaces we create. It’s the kind of idea that makes you pause and look at a building differently, as if it’s a mirror reflecting an entire people’s identity.

A New Idea: Archigenetics

From this, the study introduces a bold concept called Archigenetics. It argues that architecture isn’t just shaped by culture, climate, or resources it’s also an extension of a community’s genetic and aesthetic makeup. In other words, our buildings aren’t just what we like; they’re a reflection of who we are.

Think about it: when desert communities build homes with earthy tones and simple shapes, doesn’t that echo the landscape that shaped their lives and even their bodies? Or when northern cities craft buildings with sharp lines and cool colors, couldn’t that reflect the crisp, structured way of life there? It’s like our creations carry a piece of our collective DNA.

Key Insights at a Glance

| Region | Architectural Traits | Echoes of the People |

|---|---|---|

| Japan | Clean lines, quiet balance | Kimono’s elegance, calm expressions |

| Morocco | Vibrant patterns, bold geometry | Kaftan’s intricate designs, lively gestures |

| Greece | Symmetrical columns, smooth curves | Idealized forms in classical art |

Why This Matters

This isn’t just a thought experiment it’s got real weight. If architects and city planners understand that buildings can reflect a community’s identity, they could design spaces that feel more authentic, more like home for the people who live there. It’s also a beautiful reminder of how diverse human expression is, from the clothes we wear to the walls we build.

Next time you’re walking through a city, take a second to notice the details. Do the arches remind you of the people who live there? Do the colors tell a story of their culture? This study suggests the answer might run deeper than you think.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

In “Architecture and Identity: Reflecting Community Ties”, the article eloquently frames architecture as a mirror of cultural memory and collective belonging. By tracing how buildings serve as symbols of heritage, belief, and societal aspiration, it presents architecture not merely as shelter, but as emotional and political infrastructure. The strongest aspect lies in its recognition of local narratives and how design can echo the voice of the community. Yet, it stops short of interrogating how contemporary urban developments may dilute identity under the pressure of global homogeneity. Ten years from now, as AI-generated designs and global styles dominate, the article’s core question — “Whose identity does architecture reflect?” — will grow more urgent. Still, the piece succeeds in reminding us that true architecture is not authored solely by architects, but co-written with the people it serves.

Dive Deeper

Want to explore more? The full study, packed with stunning visuals and in-depth analysis, is available online. Check it out here.

In the end, architecture is more than just buildings. It’s a story about us our people, our essence, and the invisible threads that tie us to the world we create.

ArchUp continues to track transformations in the construction industry, spotlighting projects that embrace innovation and reshape the urban landscape. The Museum of the Future is proof that when imagination meets dedication, the impossible becomes reality.

What is “Archi-genetics”?

“Archi-genetics,” introduced by Ibrahim Nawaf Joharji, is a theory suggesting that architecture is not merely a cultural expression or a functional practice, but also has a biological and personal dimension linked to genetics and inherited identity. The theory is based on the observation that cities and architecture reflect the features and personalities of their inhabitants—similar to how pets often resemble their owners. This implies that our architectural taste and perception of beauty are encoded in our genetic makeup, and what we find aesthetically pleasing is not universally objective but rather inherited.

The theory also draws from traditional Arab “ethno-perception” (the science of physiognomy) and spatial identity, proposing that “we build what we are.” In other words, architecture is a biological and cultural extension of our personalities and genes, not just a functional or cultural construct.

Evaluation of the Theory

Unique and Innovative: “Archi-genetics” combines biology, physiognomy, and architecture in a novel way, offering a fresh perspective on the relationship between humans and the built environment.

A Valuable Addition: While there are similar concepts in architecture—such as “architectural DNA” or “architectural genes”—the direct link to genetics and inherited identity is a distinctive intellectual development.

Relevant to the Arab Context: By connecting the theory to Arab physiognomy, it gains a unique cultural dimension, making it particularly valuable in the regional context.

Not Just Ordinary Talk: The theory is grounded in years of observation and visual analysis, providing a thoughtful framework that can be developed academically and practically.

Conclusion

Ibrahim Joharji’s “Archi-genetics” is a new and unique contribution to the field of architecture. It bridges biology, culture, and personal identity, opening new avenues for understanding architecture as an extension of human genetics and identity—not just as a functional or cultural artifact. This makes it much more than a generic idea or a repetition of existing concepts.