Designing a Chicago Tower Integrating Vertical Farming and Urban Functions to Enhance Sustainability

Architectural Vision Beyond Symbolism

Imagine the Chicago skyline not merely as an expression of economic power, but as a system that supports daily life. In this vision, skyscrapers do more than define the city’s silhouette, they become active structures: growing food, harvesting rainwater, and responding to accumulated urban imbalances. This raises a fundamental analytical question: can architecture be part of an urban food system?

From Symbol to Function

Traditionally, tall towers have been associated with visual dominance and economic efficiency. Yet, this approach redirects the focus from symbolism to social function. Integrating agriculture within the building, at heights close to residents’ lives, proposes a new role for architecture that goes beyond shelter to encompass production.

Food Deserts: A Chronic Urban Issue

At the heart of the concept lies the problem of food deserts, where low-income neighborhoods in Chicago face limited access to healthy and affordable food. With grocery stores scarce, fast food becomes the most prevalent option, not by choice, but by necessity. Over time, this reality has deepened health disparities and reinforced social and economic divides.

Architecture as a Tool for Intervention

Rather than treating food deserts solely as a public policy issue, the project reads them as a design opportunity. Integrating food production and water management within the architectural fabric opens the door to direct, localized, and sustainable interventions, linking urban planning with food justice.

Programmatic Integration Redefining Food Production

Programmatically, the tower integrates vertical farming into its core, treating it not as an added element but as a fundamental urban facility. Instead of relying on long supply chains that transport food from distant rural areas, food is produced within the city itself, inside the building. As a result, the skyscraper becomes a quasi self-sufficient system, reducing transportation-related emissions and reconnecting urban communities with their direct sources of food.

From Environmental Self-Sufficiency to Food Justice

This integration extends beyond the environmental dimension to a clear social one. Local food production helps improve accessibility, especially in the most needy areas, transforming architecture from a resource consumer into an active agent in distribution. In this way, the building becomes part of the solution to chronic food imbalances, not merely a symbol of sustainability.

A Formal Language Inspired by Water

Formally, the design draws inspiration from one of the elements most associated with Chicago’s identity: water. The tower’s fluid form mimics a water droplet, evoking renewal, continuity, and resilience. Yet, this choice is not only expressive; it also has functional implications for the urban landscape.

Vertical Extension of Nature

Through this configuration, the city’s “green belt” extends upwards, reintegrating nature into the dense urban fabric. Green spaces are no longer confined to the outskirts or ground level, they become part of the skyline itself, presenting a new conception of the city’s relationship with nature: an ascending, not marginal, relationship.

An Integrated Vertical Community

Life within the tower is presented as a model of a vertical community functioning as a single unit. Residential units intertwine with commercial spaces, allowing residents to meet their daily needs, from work to shopping, within close proximity. In this way, the need for constant commuting is reduced, and the building transforms into a micro-urban environment that supports stability and social interaction.

Multiple Functions Within a Single Fabric

In addition to housing and workspaces, the tower’s floors host hotels offering short-term stays and panoramic views of the city. This function not only adds economic vitality but also enhances cultural exchange, integrating visitors into the daily rhythm of the place rather than isolating them from it.

Education as Part of Daily Life

Integrating schools within the tower rethinks the placement of education in the city. Instead of being separated at the outskirts or ground level, education becomes part of residents’ daily experience, fostering continuity between learning and community life.

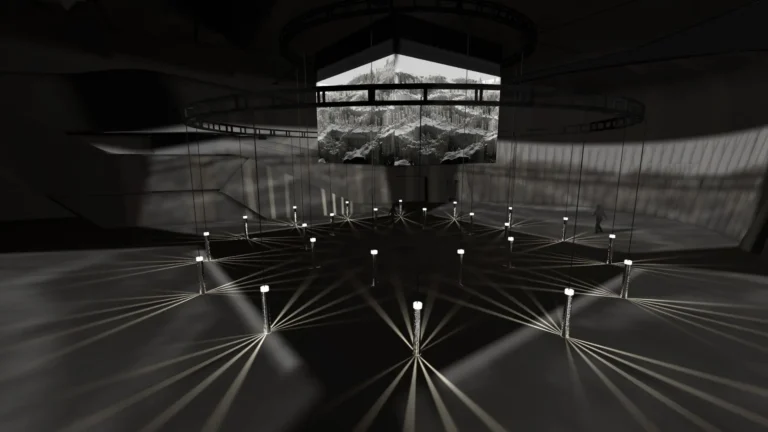

Sky Terraces as Social Spaces

At various heights, sky terraces appear as collective breathing spaces. These open green areas provide places for gathering and relaxation, reconnecting residents with nature within a dense environment. They also support the tower’s diverse functions and contribute to building a sense of belonging and shared ownership among its inhabitants.

Sustainability as a Core System

In this project, sustainability is not presented as an added feature, but as the organizing foundation of the design. Vertical farming, centered in the core, ensures a continuous supply of fresh produce, while cloud harvesting and rainwater collection systems are integrated directly into the façade, allowing highly efficient water reuse within a quasi-closed cycle.

Energy, Air, and Natural Light

Along the building’s exterior, wind turbines are integrated to generate local renewable energy. Simultaneously, the breathable atrium and natural ventilation system, supported by a Diagrid structural frame, enhance airflow and maximize natural lighting. In this way, the building not only minimizes its environmental impact but also engages in a cooperative relationship with the surrounding natural elements.

Flexible and Complex Structural System

Structurally, the tower consists of four interconnected vertical volumes, laterally supported by two layers of reinforcement systems that enhance depth and flexibility. This configuration plays a crucial role in achieving stability at great heights.

Diagrid: Between Performance and Expression

The exterior Diagrid extends through modules approximately 25 stories high, combining massive reinforcement and lateral stability within a single structural language. This strategy allows the interior spaces to be liberated, providing open areas flooded with light and air, while simultaneously enhancing the architectural clarity and expressive power of the building. Learn more about Buildings using Diagrid systems in our archive.

A Pioneering Research Project

The project transcends being a mere skyscraper to become an ambitious research endeavor. Integrating vertical farming into a mile-high tower required the development of advanced solutions for energy efficiency, water cycle management, and food systems. Balancing strict structural demands with green technologies, such as cloud harvesting and passive ventilation, pushed the boundaries of architectural engineering.

Most importantly, the focus on food deserts directly connected the project to social needs, ensuring that sustainability here is equitable and tangible, rather than merely a visual symbol or marketing slogan.

A Future Urban Icon

As a future icon for the next fifty years, the tower redefines the relationship between building and city. It goes beyond housing residents, contributing to keeping the city alive by providing food, fostering social interaction, and preserving natural resources. Explore more Cities embracing sustainable urban initiatives.

In this vision, the urban skyline is no longer just a visually impressive scene, it becomes a living system that nourishes the body, the community, and the planet, reinforcing architecture’s role as an active agent in urban sustainability.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

From an architectural perspective, the project offers exciting opportunities to rethink the role of skyscrapers within the urban environment, particularly regarding sustainability and local food production. The integration of vertical farming and multiple functions suggests the potential to transform buildings into quasi self-sufficient systems, opening the door to new experiments in contemporary architecture design.

However, several aspects remain open for review and development. For example, combining food production systems, educational facilities, and hotels within the same structure may increase structural and operational complexity, raising questions about maintenance feasibility and long-term costs. Likewise, the concept of an “integrated vertical community” requires broader study to understand residents’ interactions and their ability to meet real needs without creating constraints on movement or space usage.

Furthermore, questions concerning energy efficiency, water management, and structural flexibility in response to climatic and urban variations remain central before the project can be considered a viable model. Planners and engineers can use this project as a reference to understand the challenges of integrating multiple functions within a single structure and to develop flexible strategies for mixed-use projects, even if practical outcomes differ from the current theoretical proposal.

In summary, the project presents an architecturally rich vision grounded in experimental assumptions, yet it remains more valuable as material for reflection and future planning than as a ready-to-implement model, underscoring the need for further studies before any generalization. For more insights, visit our Archive of related architectural research.