Concepts of wildlife restoration in architecture

In an era when humanity’s detrimental impact on the environment is becoming increasingly apparent,

the concept of re-wildlife has emerged as a powerful approach to environmental conservation and ecological restoration.

In line with the growing interest in landscape architecture in recent years,

The idea of removing human interference from our natural surroundings in order to restore a stable equilibrium seems to offer an ethereal and low-effort means of correcting fundamental climatic errors.

But is lack of intervention with nature what re-wildlife is all about, and how does that relate to architecture and design?

We look at basic concepts, applications, and examples to find out.

At its core, re-wildlife aims to reverse the effects of habitat loss, species decline,

and ecosystem degradation by allowing nature to reclaim its inherent spaces and processes.

The movement represents a bold shift from traditional systematic conservation practices

and instead embraces a restorative idea of coexistence with a thriving landscape.

Driven by efforts around the United Nations Decade of Ecosystem Restoration which runs from 2021 to 2030,

Ireland, Sweden, Nigeria, Australia, India, Chile,

USA and Indonesia are just a few of the countries already implementing wildlife reintroduction projects according to a map from the World Wildlife Restoration Alliance.

In line with the interpretation of environmental historian Laura J. Martin,

re-wildlife may at first appear to conflict with building or design efforts;

But there are a number of key concepts related to the idea that can actually be supported by architectural structures and inspiring design.

Finding innovative ways for humans to speed up the process of restoring nature, or to facilitate its conservation,

or the construction of animal migration paths and natural habitats,

are interventions chosen in line with goals of philosophy that are often interpreted as strictly “laissez-faire”.

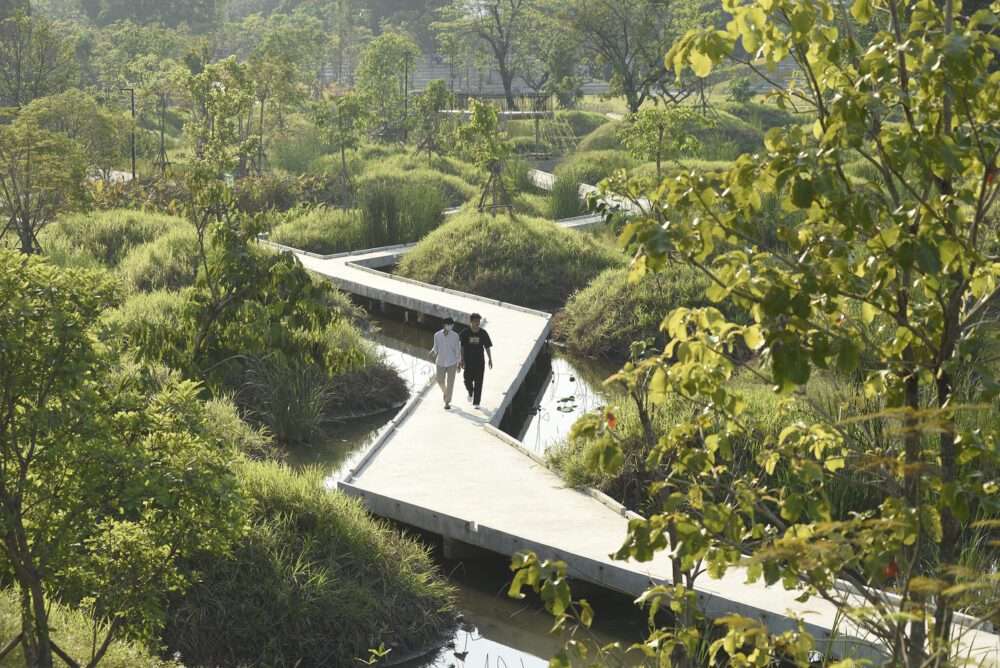

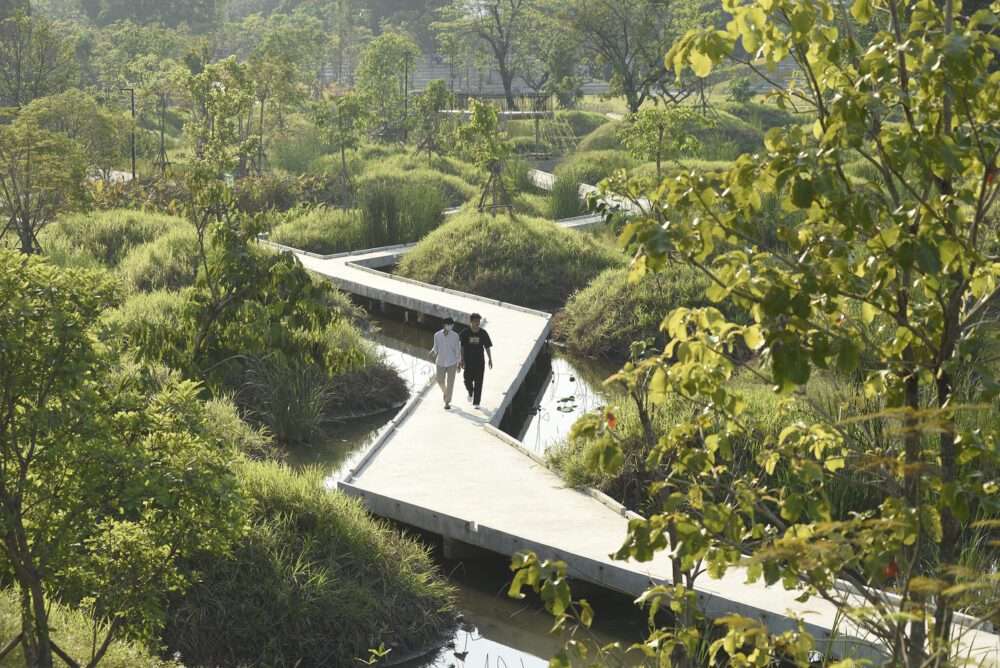

Habitat connection

Habitat connectivity involves creating or maintaining corridors that allow species to move freely between fragmented habitats.

Re-wildlife initiatives often focus on creating these corridors or wildlife crossings to facilitate the movement of animals,

and to assist with the genetic diversity, adaptation, and general health of populations.

While pathways can be formed naturally through select environmental measures,

The recent Cave_bureau exhibition at the Luciana Museum of Modern Art proposes to actively create one such corridor in their hometown of Nairobi, Kenya,

to assist the indigenous Maasai people in grazing cattle as well as restoring the area and other wildlife.