Architecture Under a Rotating Sky

How the Coriolis Effect Quietly Shapes the Built World

Architecture is rarely discussed through the lens of planetary physics. We are accustomed to viewing our cities as the products of human decisions, ink lines, and zoning masterplans. Yet, the deeper truth often absent from design studios is that the immense forces that shaped our settlements were never architectural in origin; they were atmospheric, geographic, and fundamentally planetary.

The idea for this discourse did not emerge from a construction site or a design journal, but from a long-form scientific documentary about Mars. As the program unfolded the strange surface patterns of the Red Planet and the behavior of its atmosphere, one concept kept returning with rhythmic regularity: The Coriolis Effect. What initially appeared as a distant scientific abstraction soon revealed itself as a foundational truth governing Earth, and consequently, the environments we build upon it.

Architecture, in its essence, does not exist in a vacuum. It is an entity inseparable from climate, geography, and the forces that govern them. This is where Architectural Research must occasionally step outside its conventional boundaries and look upward or rather, inward toward the mechanics of the planet itself—treating architecture as a consequence of cosmic systems rather than a standalone artifact.

Physics Preceding Design

The Coriolis effect describes the apparent deflection of moving objects when observed within a rotating reference frame. Because Earth rotates on its axis, air masses, ocean currents, and even long-distance trajectories do not move in straight lines; they curve. In the Northern Hemisphere, this deflection bends to the right; in the Southern Hemisphere, to the left. While this concept has been mathematically formalized since the 17th century, what concerns architects is not the equation, but its spatial consequences.

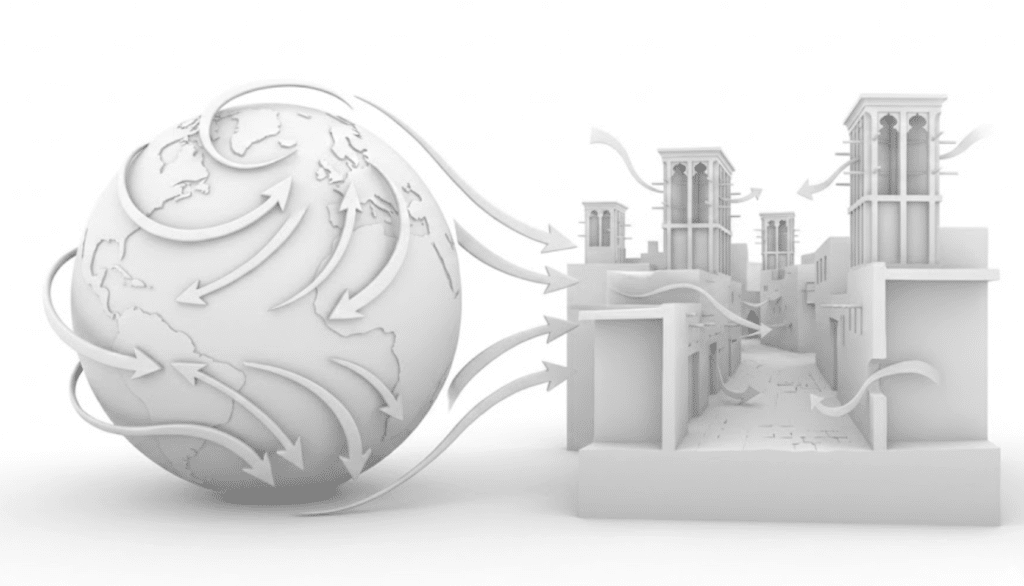

Global wind systems, monsoon cycles, and ocean currents are all structured by this rotational effect. These systems, operating consistently over millennia, determined where deserts formed and where temperate zones stabilized. Consequently, the Cities that emerged within these zones did not do so arbitrarily. Their form, density, and spatial logic evolved as long-term responses to these invisible forces.

Ancient Wisdom and Modern Hubris

Traditional architecture understood this intuitively. The internal courtyards of hot climates, narrow shaded streets, and thick masonry walls were not merely stylistic or aesthetic choices. They were “climatic negotiations.” Prevailing wind directions, solar exposure, and thermal mass were factors that shaped Architecture and its typologies long before scientific terminology existed. What we now describe through physics was once embedded in craft and lived experience.

However, with the Industrial Revolution, modern architecture attempted to detach itself from these constraints. Mechanical systems promised total control over the climate. Glass towers appeared in the heart of deserts, and standardized construction techniques spread across radically different environments. That was a moment of philosophical shift in design, where we replaced “adaptation” with “energy.”

The Return to Environmental Determinism

Today, that overconfidence is being tested. With increasing climate volatility and the inevitability of energy efficiency, architecture is being pulled back into a forced dialogue with the environmental forces it ignored for a century. The return to passive strategies, orientation, and natural ventilation reflects a growing awareness that buildings must once again respond to planetary behavior. This conversation is no longer theoretical; it has become the core of Sustainability.

Mars offers an extreme “rehearsal” for this reality. Any future architecture there will be dictated entirely by atmospheric physics. There will be no room for aesthetic autonomy; survival precedes expression. In this sense, Martian architecture becomes a distilled version of what Earth is slowly rediscovering: design constrained by physics, not fashion.

On Earth, the relationship is more subtle but no less real. Coastal cities shaped by prevailing winds, inland settlements aligned against heat and dust all reflect long-term atmospheric behavior. Even Construction techniques evolved around these conditions, favoring certain structural systems over others depending on climatic stress.

Materials themselves tell this story. The use of stone, adobe, timber, or concrete has always been tied to thermal performance and environmental availability. Today, this lineage continues through a renewed interest in the efficiency of Building Materials and their life-cycle performance under new constraints.

Conclusion: Architecture is Not Static

The Coriolis effect does not design buildings by hand, but it designs the climate systems that architects must ultimately answer to. Ignoring those systems was a “privilege” enabled by cheap energy and technological optimism—a privilege that is now fading.

The future of architecture may not belong to those who produce the most radical forms, but to those who understand how planetary mechanics quietly shape habitability. This understanding will influence everything from urban planning to facades, and from major Projects to interior comfort.

In this sense, architecture is not static. It moves with the Earth. It adapts within a rotating frame, shaped by forces older than any civilization. Under a rotating sky, no building is truly neutral.

What traditional discourse often overlooks is the paradigm shift in our “tools of perception.” In the past, architects relied on cumulative observation (trial and error) to understand the impact of the Coriolis effect and prevailing winds on their architectural massing. Today, we have shifted from “passive intuition” to “active simulation.”

Using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) software, we are now able to see the invisible. We can model how air wraps around a skyscraper and how vortex shedding forms—forces that can threaten structural integrity or pedestrian comfort. This digital understanding allows us to sculpt architectural masses (Aerodynamic shaping) to flirt with the wind rather than resist it, transforming planetary forces from an “enemy” to be repelled by thick walls into a “partner” that contributes to cooling the building and generating its energy. The coming architecture is aerodynamically distinct—not just in form, but in performance.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

This article explores the profound intersection of planetary physics and Contemporary Architecture, identifying the Coriolis Effect as a silent force that structures climate and, consequently, the Urban Fabric. It analyzes the professional shift from “traditional intuition” to “active simulation” using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), redefining the building as an aerodynamic entity. However, a critical inquiry remains regarding the Functional Resilience of this tech-centric approach; does the obsession with aerodynamic shaping risk prioritizing mechanical performance over the Human Scale and social context of architectural space? The analysis warns of buildings becoming mere “wind-negotiating machines” lacking tactile Material Expression. Nevertheless, this foresight is vital for achieving genuine Sustainability amidst cosmic climate volatility, asserting that wise architecture negotiates with the rotating sky rather than resisting it.