Documerica: The Moment America Forced Itself to Look in the Mirror

By Ibrahim Fawakherji

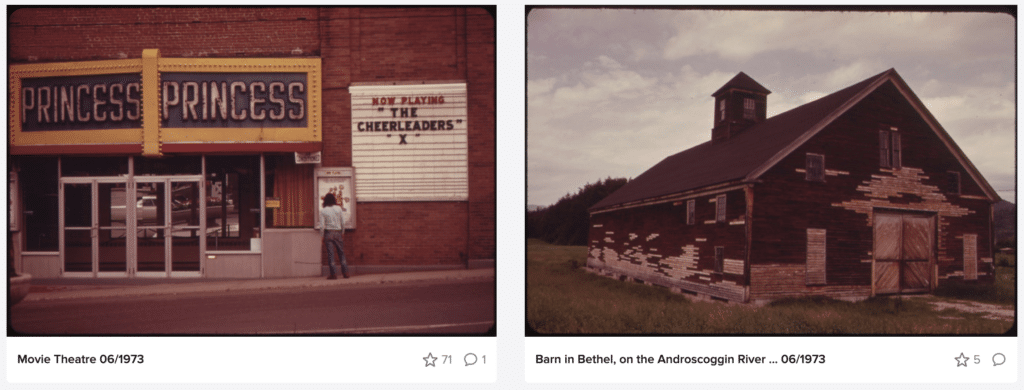

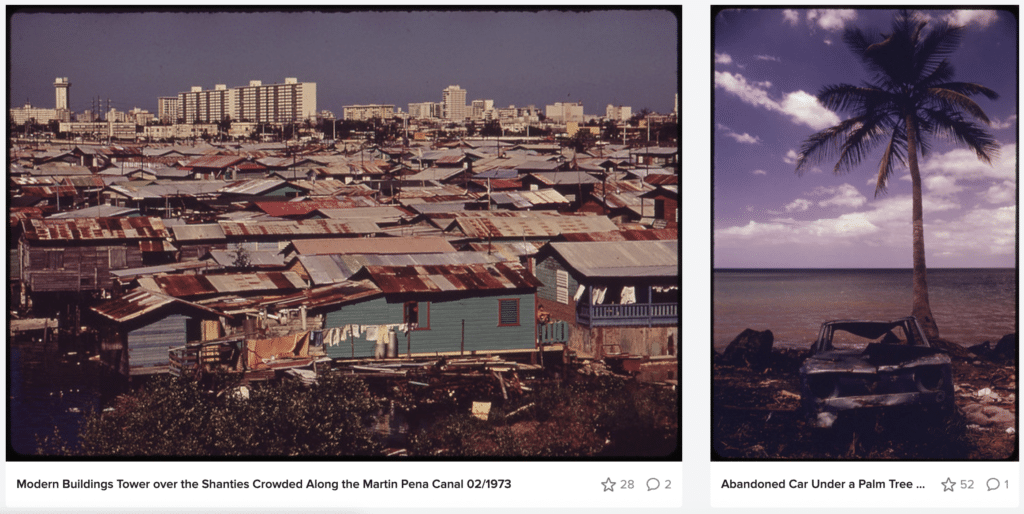

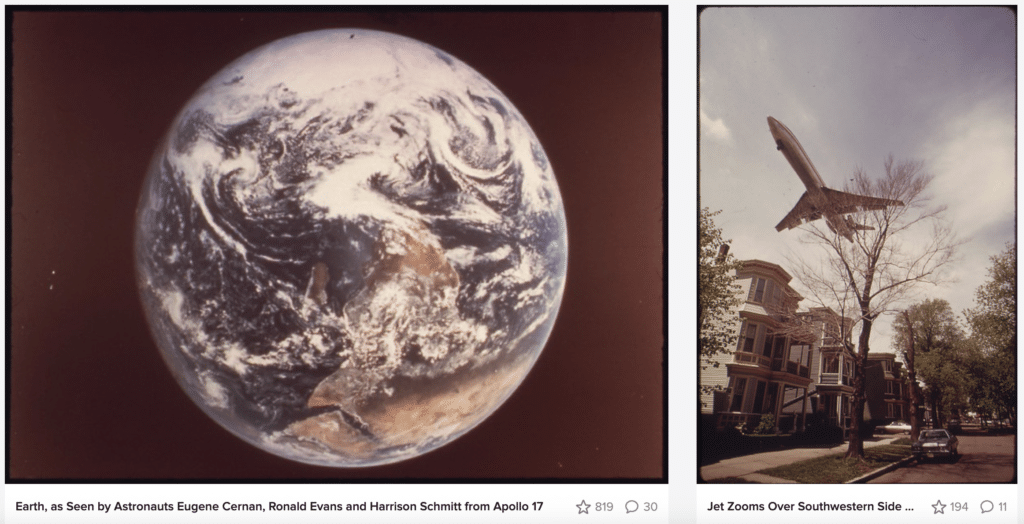

In 1969, the United States inhabited a state of profound schizophrenia. It was the year humanity, propelled by American engineering, first set foot on the lunar surface. Yet, while the world watched the flickering gray images of the moon landing, a much darker set of visuals was emerging from the American interior. The Cuyahoga River in Ohio had caught fire, ignited by a thick sludge of industrial debris and chemical waste. This paradox—a nation capable of conquering the vacuum of space while failing to protect its own waterways—birthed one of the most significant visual and political records in modern history: the Documerica project.

What followed was not merely an artistic endeavor. It was a visceral reaction to a collective national shock. The burning river was a symbolic collapse of the narrative of progress. It forced a question that the architectural and political establishment could no longer ignore: What is the true cost of the modern lifestyle?

Within this climate of anxiety, President Richard Nixon made an uncharacteristically aggressive entry into environmental policy. His motivations were less about romanticism and more about the cold calculus of political survival. With the 1972 election on the horizon and public sentiment shifting toward ecology, the Nixon administration established the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970 and activated the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts. However, policy required a face, and the newly formed EPA needed a way to justify its existence to a skeptical public. Thus, in 1971, Documerica was born.

The project was led by Gifford Hampshire, who envisioned a federal initiative to document the environmental and urban state of the nation. Between 1971 and 1977, a group of approximately 70 photographers was dispatched across the country. They visited factories, housing estates, suburban cul-de-sacs, and decaying inner cities. What distinguished Documerica was its brutal honesty. It was not intended to polish the American image but to expose it. The archive, which now holds more than 22,000 images in the National Archives, remains a foundational pillar for anyone engaged in Architectural Research today.

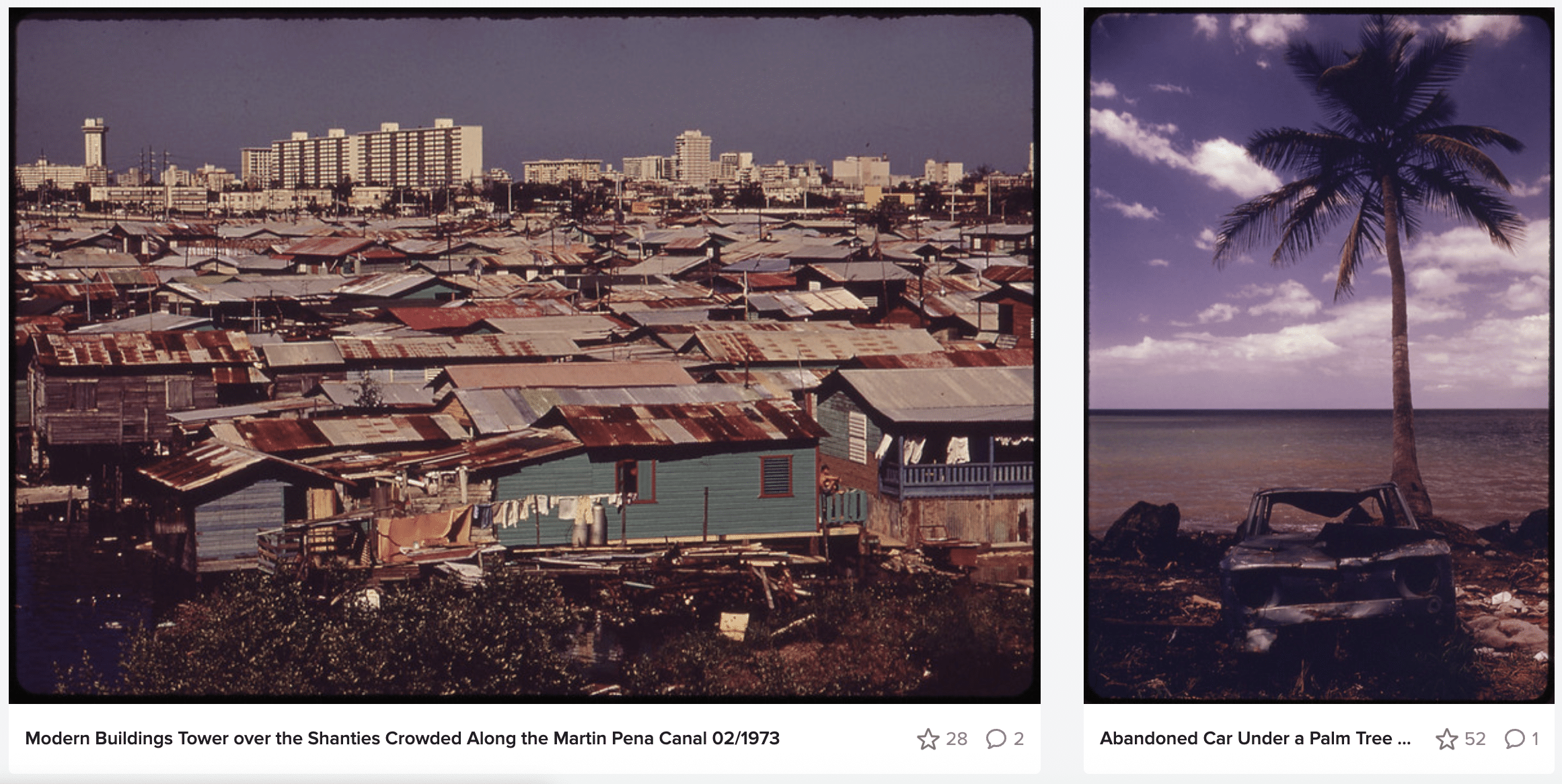

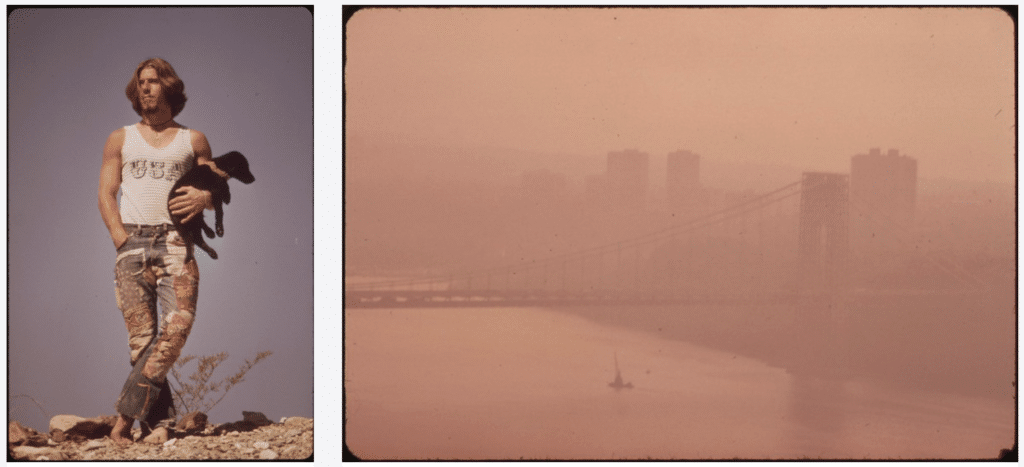

As an architect, reading these images reveals a narrative that goes far beyond pollution. Documerica documented the very DNA of the 20th-century American city. It captured the aggressive expansion of the suburban sprawl, the absolute dependency on the automobile, and the relentless horizontal growth that defined the era. These were not just environmental snapshots. They were records of planning decisions and architectural philosophies. The images of endless highways and massive industrial complexes adjacent to residential neighborhoods captured a systemic failure of zoning that we are still attempting to rectify in modern Cities.

The project took an even more somber turn in 1973 with the onset of the Arab Oil Embargo. Suddenly, the cheap fuel that served as the lifeblood of the American suburban experiment vanished. The images of mile-long queues at gas stations, captured by Documerica photographers, became a testament to the fragility of a consumer model that had previously seemed indestructible. The project, perhaps unintentionally, documented the exact moment the American Dream hit a structural wall.

From a technical perspective, the physicality of the project added to its gravity. This was the era of Kodak dominance, where every shot was a material decision. In the pre-digital age, photography was an expensive and deliberate act. A photographer had to weigh the importance of a scene before pressing the shutter. This material constraint forced a level of depth and intentionality that is often lost in our current era of infinite digital imagery. These photographers were not just taking pictures. They were making architectural and social judgments.

“DOCUMERICA was not a photo essay, it was environmental policy translated into scale. By 1974, EPA’s program had generated over 81,000 photographs through 100+ photographers, then curated a hard archive of 22,000+ images at the National Archives, effectively creating America’s first visual baseline of its urban and ecological contradictions. That is precisely what an independent platform can do today: build an evidentiary memory that outlives headlines. ArchUp’s strongest parallel is not in documenting buildings, but in documenting the lifestyles and decisions that buildings silently obey.”

What makes Documerica relevant in 2026 is its foundational philosophy. It represents a state decided to look at itself with startling clarity through a relatively independent visual medium. This concept aligns directly with the contemporary mission of independent platforms. Documentation is not an end in itself. It is a tool for systemic understanding. When we discuss Sustainability at ArchUp, we are not interested in the sanitized language of corporate brochures. We are interested in the “Documerica approach,” which is to see the reality as it is, no matter how uncomfortable, and then build an architectural position from that truth.

Architecture is, in its essence, a physical manifestation of a lifestyle. When the photographers of Documerica captured the smog over Los Angeles or the desolate public housing projects of Chicago, they were documenting architectural decisions before they were environmental ones. The themes we debate today—carbon footprints, adaptive reuse, and urban density—were all present in those archives five decades ago. They were warnings that went unheeded for too long.

This brings us to a recurring question in the history of the built environment: Why is a visual shock always required to trigger systemic change? Why was it not enough to know the rivers were polluted? Why did we need to see them burning? Our current era faces a similar crisis. We possess the data showing that our current building patterns are unsustainable, yet the industry moves with a glacial pace. Perhaps it is because we have not yet seen the full picture of our own era’s failures.

While Documerica was not strictly a series of Projects in the architectural sense, it provided architects with an invaluable archive of context. it serves as a reminder that any discussion about Architecture that ignores the broader political and environmental context is inherently incomplete. It links politics to the city, consumption to space, and the image to the executive decision.

Today, as the global conversation returns with renewed urgency to themes of consumption, climate, and the urban future, Documerica feels more contemporary than ever. The tools have changed. Our images are faster, lighter, and more ubiquitous. Yet the challenge remains the same. The goal is not simply to document more, but to understand more. We must look at our buildings and our cities not as technical solutions, but as mirrors of our collective values.

Perhaps the most enduring lesson from this 1970s experiment is that architecture can be a form of truth-telling. The mirror may not always show us a flattering image, but it is an essential tool if we intend to design a different future. Documerica proved that before you can fix a city, you must first have the courage to see it.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

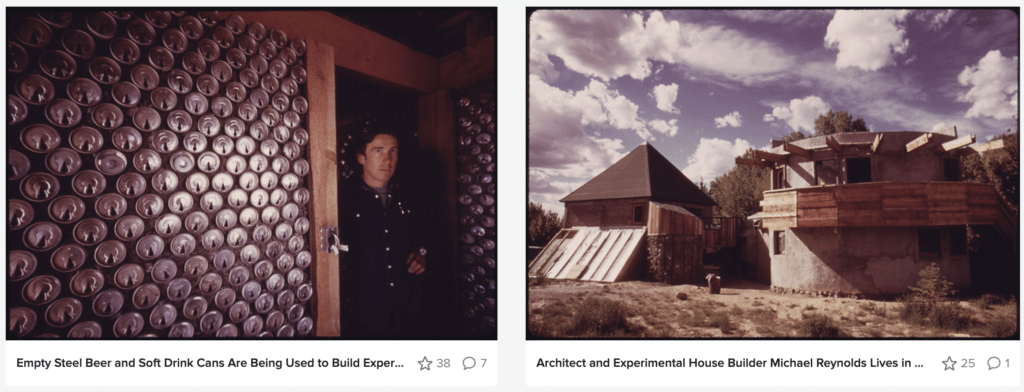

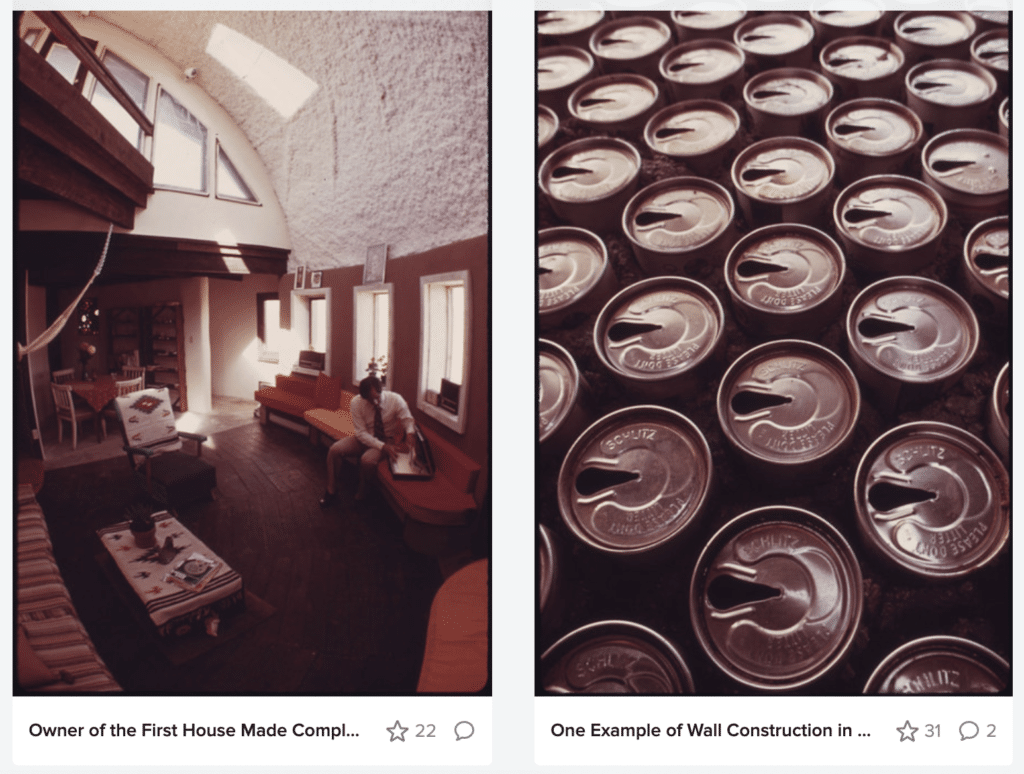

This article provides a profound dissection of the “Documerica” project, framing it not merely as a photographic archive, but as a visceral recording of the 20th-century American Urban Fabric at its moment of systemic collapse. It captures the paradox of a nation conquering space while failing to sustain its own Contextual Relevance, utilizing a visual language that exposed the aggressive expansion of suburban sprawl and industrial intrusion. From an architectural perspective, the core critique addresses the “schizophrenia of progress”; the project documented how zoning failures and automobile dependency were architectural decisions long before they became environmental catastrophes. By showcasing experimental responses like Michael Reynolds’ Sustainable Vernacular Earthships—built from discarded materials like beer cans—Documerica highlighted the urgent need for a shift in Material Expression. The analysis warns that our current era possesses the same unsustainable data but lacks the “visual shock” necessary to trigger radical change. Ultimately, the project remains a foundational pillar for Architectural Research, challenging us to view our buildings not as technical solutions, but as mirrors of our collective values and their long-term Sustainability.

Image Copyright & Research Use Notice

All images referenced or displayed are used strictly for research, educational, and critical analysis purposes.

Copyright remains with the original rights holders, and no commercial reproduction or redistribution is intended.

If you are a copyright owner and believe content has been used in error, please contact us for prompt review or removal.

★ ArchUp Technical Analysis

Technical Note on Documerica Project:

This article analyzes the EPA’s Documerica project (1971-1977) as a pioneering model of “Visual Urban Audit,” demonstrating how systematic documentation serves as a critical tool for evaluating the built environment and environmental policy.

The structural strategy of the project relied on a decentralized “visual sampling” framework, dispatching 70 photographers to document diverse American landscapes. Unlike rigid architectural surveys, this strategy focused on the interface between industrial infrastructure and human habitation.

Regarding materials and efficiency, the analysis emphasizes the “analog materiality” of the era. The physical limitations of film imposed a “deliberate efficiency” on the documentation process; every frame was a calculated architectural critique rather than a disposable digital image.

In terms of functional performance, the project operated as a “societal mirror” to bypass sanitized corporate narratives and trigger systemic awareness of pollution and urban failure.

Related Insight: Please refer to this article to understand the context of urbanization:

Understanding Urban Housing Challenges: Analyzing Population Growth and Urbanization.