Floating cities between the past and the future

Floating cities between the past and the future,

The threat of climate change looms ahead.

Sea level rise will put more than 410 million people at risk of losing their livelihoods.

Coastal cities are choked with tall buildings and traffic-clogged roads, and land is underutilized.

Putting together these problems, architects around the world have proposed a possible answer – floating cities.

The future of living on water looks like a radical shift in the way people live, work and play.

Vernacular precedents prove otherwise, providing inspiration for what our cities can become.

According to the standard civilization narrative,

the first human settlements flourished near bodies of water — rivers, lakes, wetlands, and seas.

Bedouins needed water for drinking and hunting, as did agricultural societies for farming.

The land was also more fertile as it could easily be nourished from the water source.

As a result, humans established themselves at the intersection of land and sea,

building and growing their settlements in either direction.

Kampong Ayer in Brunei, Makoko in Lagos, Ganvie in Benin,

and the swamps of Mesopotamia provide a peek into the aquatic lifestyle.

They provide a starting point for imagining how our lives will be shaped by new maritime settlements.

A more contemporary idea of seaside towns began to emerge in the 1960s with Buckminster Fuller’s City and Tokyo Bay plan designed by Kenzo Tange.

Water architecture

These utopian projects are also developed based on current ideas of hydro engineering – proposing modern amenities, advanced mobility networks, and orderly growth in addition.

Water-based architecture built in general usually consists of tectonics such as stilt houses and,

more recently, floating frames made of hollow plastic elements.

The ideals introduced in the era of modernism featured buoyant structures made of steel and explored new methodologies for keeping buildings afloat.

With advances in technology comes innovation.

In the 21st century, architects and the public are beginning to take the idea of water cities more seriously.

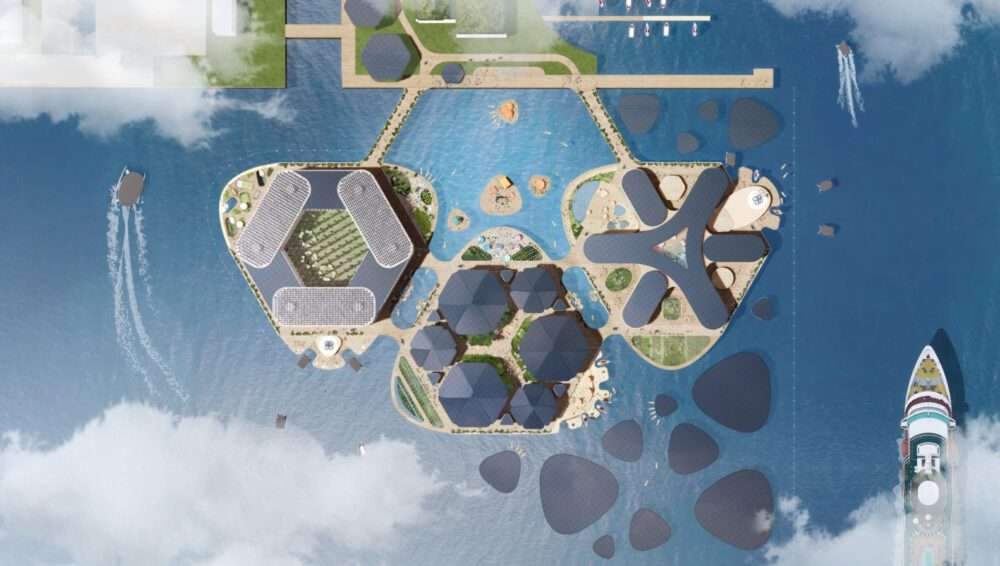

Where the most famous design at the moment is Oceanix City by architect Bjarke Ingles,

Developed in partnership with UN-Habitat and the blue technology company OCEANIX.

The vision for the world’s first model sustainable city on water will be in Busa, South Korea, an important maritime city in the region.

The island-like colony will be anchored to the sea floor by a biorock that will house an artificial reef.

Food will be grown on floating farms and through aquaculture,

and drinking water will be obtained from desalinated sea water.

Oceanix is in its early conceptual stages with great potential.

Showcasing high tech concepts

Similar high-tech concepts in Lilypad have been demonstrated at Vincent Callebaut’s Seasteading Institute and Phil Pauley’s Sub-Biosphere 2.

Already before these visions, there is a state-of-the-art floating housing project in Amsterdam.

Due to the environmental awareness in the Netherlands,

the project titled Waterbuurt successfully addresses the imminent threat in the low-lying country of sea level rise.

In Lago, a new coastal city is being developed through land reclamation, similar to the projects along the UAE coast.

While the visible environmental damage has prompted a conversation about floating cities, doubts remain.

Political ideas about jurisdiction and ownership will require reconsideration.

Such expensive projects may only be within the reach of certain segments of society and at affordable prices.

Environmentalists have also harshly criticized land reclamation projects for disrupting ocean ecosystems and risking floods.

And the future of urban life may closely mimic its lesser-known past.

In times of uncertainty, case studies of traditional architecture and systems of indigenous cultures can provide learning opportunities.

Settlements are built to co-exist with nature’s established patterns,

contributing as much as they extract from the environment.

According to the Institute for Economics and Peace,

more than 1 billion people will be placed in regions with insufficient infrastructure to withstand sea level rise by 2050.

At this rate, it would take more than 9,000 Oceanix cities to resettle climate refugees.

Floating cities are not a single solution to sea level rise and climate change,

but they could be an impactful step towards a cure.

This transformation will require a reassessment of lifestyles, legal structures, and man-made ecosystems.

New frontiers for aquatic lifestyles look hopeful.

For more architectural news