Luxor Temple: Where Architecture Preserves Civilizations in Stone

A Pharaonic column adorned with symbolic reliefs of Ma’at stands within Abu Al-Haggag Mosque, blending sacred Pharaonic elements with Islamic prayer space. This integration reflects adaptation over erasure. (Image © Sherif Sonbol / Getty Images)

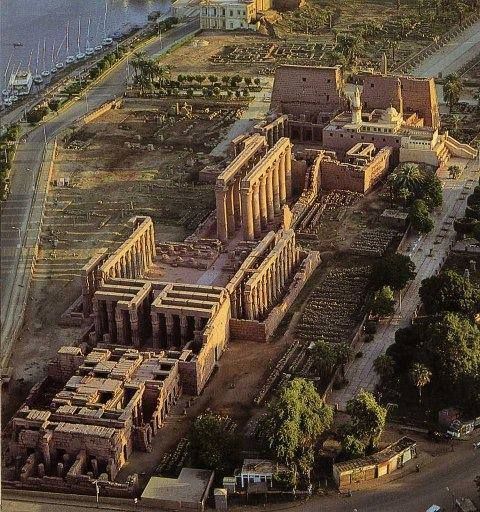

In Luxor, time is not measured in years, but in layers layers of stone, rituals, and beliefs that have accumulated without erasing one another. Inside Luxor Temple, a visitor can enter an Islamic mosque more than eight hundred years old, then look up to find Pharaonic columns covered with carvings of ancient Egyptian deities, foremost among them the goddess Ma’at, symbol of justice and cosmic order. It is a scene that feels like an architectural joke, yet in truth it is a profoundly civilizational lesson in architecture, one that can be read within a broader context of the history of cities.

This place does not narrate the history of a single religion; rather, it tells the story of architectural design when it refuses demolition and chooses accumulation.

Architecture as a Memory That Does Not Erase What Came Before

Contrary to what ideological conflicts might suggest, architecture is often calmer and wiser. Instead of removal, it tends toward reuse. Luxor Temple is a rare example of this approach: it was not demolished to make way for something new, but instead transformed and adapted across successive eras, becoming a unique model of temporally layered structures.

In the Pharaonic era, the temple was constructed as a sacred space shaping the relationship between humanity and the cosmos. The massive columns, straight axes, and reliefs recounting myths of creation and divine balance were not merely aesthetic elements, but an architectural language expressing a complete philosophical worldview. Today, they represent rich material for any contemporary architectural research.

From Luxor Temple to Cathedral: The Transfer of Sacredness

With the arrival of Christianity in Egypt, the temple was not regarded as a pagan structure that needed to be erased, but as a sacred space capable of transformation. Parts of it were reused as a Coptic cathedral. This shift reflects an ancient understanding of sacredness as being tied to place itself, not solely to interior design, and to the way internal spaces are reconfigured.

Here lies the paradox: the temple did not lose its sanctity it merely changed its symbolic language.

Abu Al-Haggag Mosque: Islam Above the Layers of History

In the 7th Hijri century, during the reign of Sultan Al-Salih Najm Al-Din Ayyub, the Abu Al-Haggag Al-Luxori Mosque was built atop the remains of the cathedral. The mosque was not separated from the temple but integrated into it; its minaret rises from the heart of a Pharaonic building thousands of years old, offering a rare example of how construction adapts to an existing historical context.

Architecturally, this mosque was not designed from scratch, but rather adapted to an existing space:

- A qibla oriented within a space not originally intended for Islamic prayer

- Pharaonic columns surrounding worshippers

- Elevated floor levels reflecting centuries of accumulation

These are not design flaws, but honest markers of a living archive that can be revisited as part of the human architectural platform of knowledge.

Do Beliefs Clash Within the Same Space?

One might ask: how can a Muslim pray in a mosque surrounded by carvings of ancient gods?

The answer lies in understanding the difference between an archaeological symbol and a living deity. Today, these carvings are historical documents, not objects of worship, and they carry no devotional meaning in the consciousness of the worshipper.

More important than any legal ruling, however, is the deeper meaning:

that difference can coexist without negating one another a lesson that can be read as an editorial introduction to spatial tolerance.

Ma’at and Abu Al-Haggag: Meaning Beyond Names

A striking paradox is that the goddess Ma’at, who embodied justice and balance in ancient Egyptian thought, appears carved within a mosque attributed to a Sufi saint known for asceticism, justice, and love for people.

It is as if great values preceded religions, transcended their names, and remained present in stone just as buildings outlive any discourse.

When Architecture “Jokes”

This is not mockery, but wisdom.

Architecture here does not ridicule beliefs; it exposes the fragility of the idea of rupture. Quietly, it tells us:

What is built upon stone is not erased by time, but enriched by an added layer.

In Luxor Temple, it is not merely a mosque within a temple, nor a cathedral buried in memory, but an entire human history that chose to coexist within a single site an example of how architecture can remain ever-relevant in global news.

Here, the scene does not appear contradictory, but astonishing…

As if architecture and archaeology, after thousands of years, decided to joke and teach us a lesson.

A Quick Architectural Snapshot

This unique architectural composition is located within Luxor Temple in Upper Egypt, where Pharaonic, Christian, and Islamic layers overlap in a single site. The massive stone structure, extending across centuries, reflects religious and functional transformations without demolition, preserving the site’s historical and spatial dimensions.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

Layer 1 – Non-Architectural Data reveals repeated behaviors in urban mobility: extended commutes and high personal vehicle reliance dictate the need for private parking and wide vehicular access. Consumption patterns favor individual ownership over shared resources. Financing models prioritize quick ROI, discouraging multi-phase or experimental projects. Labor structures are highly segmented, producing silos between engineering, procurement, and construction.

Layer 2 – Decision Frameworks show that regulations, zoning codes, and insurance standards reward standardization. CAPEX sensitivity and risk-averse policies limit deviation from tested layouts. Operational constraints enforce predictable circulation patterns. Cultural pressures around status and privacy bias decisions toward isolated units and buffered façades.

Layer 3 – Architectural Outcome manifests as a multi-unit residential complex with repetitive massing, defensive spacing, large surface parking, and a layout optimized for short-term efficiency. This project is the logical outcome of car dependency + risk-averse regulations + segmented labor structures. Related case studies in urban mobility patterns support these correlations.