Modern art

| History of art |

|---|

|

Periods

|

|

Regions

Art of the Middle East

Art of Asia

Art of Europe

Art of Africa

Art of the Americas

Art of Australia Art of Oceania |

|

Religions

|

|

Techniques

|

|

Types

|

|

Modern art includes artistic work produced during the period extending roughly from the 1860s to the 1970s, and denotes the styles and philosophies of the art produced during that era.[1] The term is usually associated with art in which the traditions of the past have been thrown aside in a spirit of experimentation.[2] Modern artists experimented with new ways of seeing and with fresh ideas about the nature of materials and functions of art. A tendency away from the narrative, which was characteristic for the traditional arts, toward abstraction is characteristic of much modern art. More recent artistic production is often called contemporary art or postmodern art.

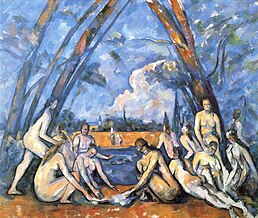

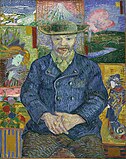

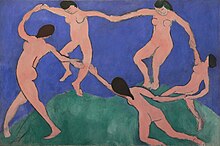

Modern art begins with the heritage of painters like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec all of whom were essential for the development of modern art. At the beginning of the 20th century Henri Matisse and several other young artists including the pre-cubists Georges Braque, André Derain, Raoul Dufy, Jean Metzinger and Maurice de Vlaminck revolutionized the Paris art world with “wild”, multi-colored, expressive landscapes and figure paintings that the critics called Fauvism. Matisse’s two versions of The Dance signified a key point in his career and in the development of modern painting.[3] It reflected Matisse’s incipient fascination with primitive art: the intense warm color of the figures against the cool blue-green background and the rhythmical succession of the dancing nudes convey the feelings of emotional liberation and hedonism.

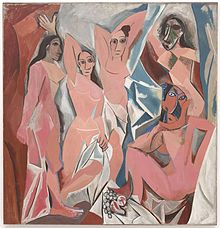

At the start of 20th-century Western painting, and initially influenced by Toulouse-Lautrec, Gauguin and other late-19th-century innovators, Pablo Picasso made his first Cubist paintings based on Cézanne’s idea that all depiction of nature can be reduced to three solids: cube, sphere and cone. With the painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), Picasso dramatically created a new and radical picture depicting a raw and primitive brothel scene with five prostitutes, violently painted women, reminiscent of African tribal masks and his own new Cubist inventions. Analytic cubism was jointly developed by Picasso and Georges Braque, exemplified by Violin and Candlestick, Paris, from about 1908 through 1912. Analytic cubism, the first clear manifestation of cubism, was followed by Synthetic cubism, practiced by Braque, Picasso, Fernand Léger, Juan Gris, Albert Gleizes, Marcel Duchamp and several other artists into the 1920s. Synthetic cubism is characterized by the introduction of different textures, surfaces, collage elements, papier collé and a large variety of merged subject matter.[4][5]

The notion of modern art is closely related to modernism.[a]

History

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge: Two Women Waltzing, 1892

Paul Gauguin, Spirit of the Dead Watching 1892, Albright-Knox Art Gallery

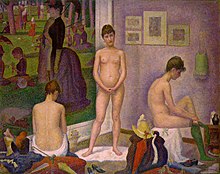

Georges Seurat, Models (Les Poseuses) 1886–88, Barnes Foundation

The Scream by Edvard Munch, 1893

Pablo Picasso, Family of Saltimbanques, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Jean Metzinger, 1907, Paysage coloré aux oiseaux aquatiques, oil on canvas, 74 x 99 cm, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

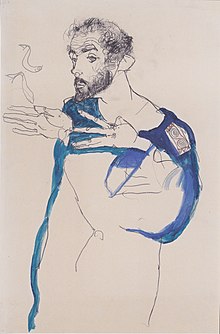

Klimt in a light Blue Smock by Egon Schiele, 1913

I and the Village by Marc Chagall, 1911

Black Square by Kasimir Malevich, 1915

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917. Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz

Wassily Kandinsky, On White II, 1923

Édouard Manet, The Luncheon on the Grass (Le déjeuner sur l’herbe), 1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Roots in the 19th century

Although modern sculpture and architecture are reckoned to have emerged at the end of the 19th century, the beginnings of modern painting can be located earlier.[7] The date perhaps most commonly identified as marking the birth of modern art is 1863,[7] the year that Édouard Manet showed his painting Le déjeuner sur l’herbe in the Salon des Refusés in Paris. Earlier dates have also been proposed, among them 1855 (the year Gustave Courbet exhibited The Artist’s Studio) and 1784 (the year Jacques-Louis David completed his painting The Oath of the Horatii).[7] In the words of art historian H. Harvard Arnason: “Each of these dates has significance for the development of modern art, but none categorically marks a completely new beginning …. A gradual metamorphosis took place in the course of a hundred years.”[7]

The strands of thought that eventually led to modern art can be traced back to the Enlightenment.[b] The important modern art critic Clement Greenberg, for instance, called Immanuel Kant “the first real Modernist” but also drew a distinction: “The Enlightenment criticized from the outside … . Modernism criticizes from the inside.”[9] The French Revolution of 1789 uprooted assumptions and institutions that had for centuries been accepted with little question and accustomed the public to vigorous political and social debate. This gave rise to what art historian Ernst Gombrich called a “self-consciousness that made people select the style of their building as one selects the pattern of a wallpaper.”[10]

The pioneers of modern art were Romantics, Realists and Impressionists.[11][failed verification] By the late 19th century, additional movements which were to be influential in modern art had begun to emerge: post-Impressionism and Symbolism.

Influences upon these movements were varied: from exposure to Eastern decorative arts, particularly Japanese printmaking, to the coloristic innovations of Turner and Delacroix, to a search for more realism in the depiction of common life, as found in the work of painters such as Jean-François Millet. The advocates of realism stood against the idealism of the tradition-bound academic art that enjoyed public and official favor.[12] The most successful painters of the day worked either through commissions or through large public exhibitions of their own work. There were official, government-sponsored painters’ unions, while governments regularly held public exhibitions of new fine and decorative arts.

The Impressionists argued that people do not see objects but only the light which they reflect, and therefore painters should paint in natural light (en plein air) rather than in studios and should capture the effects of light in their work.[13] Impressionist artists formed a group, Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs (“Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers”) which, despite internal tensions, mounted a series of independent exhibitions.[14] The style was adopted by artists in different nations, in preference to a “national” style. These factors established the view that it was a “movement”. These traits—establishment of a working method integral to the art, establishment of a movement or visible active core of support, and international adoption—would be repeated by artistic movements in the Modern period in art.

Early 20th century

Pablo Picasso Les Demoiselles d’Avignon 1907, Museum of Modern Art, New York

Henri Matisse, The Dance I, 1909, Museum of Modern Art, New York

Among the movements which flowered in the first decade of the 20th century were Fauvism, Cubism, Expressionism, and Futurism.

During the years between 1910 and the end of World War I and after the heyday of cubism, several movements emerged in Paris. Giorgio de Chirico moved to Paris in July 1911, where he joined his brother Andrea (the poet and painter known as Alberto Savinio). Through his brother he met Pierre Laprade, a member of the jury at the Salon d’Automne where he exhibited three of his dreamlike works: Enigma of the Oracle, Enigma of an Afternoon and Self-Portrait. During 1913 he exhibited his work at the Salon des Indépendants and Salon d’Automne, and his work was noticed by Pablo Picasso, Guillaume Apollinaire, and several others. His compelling and mysterious paintings are considered instrumental to the early beginnings of Surrealism. Song of Love (1914) is one of the most famous works by de Chirico and is an early example of the surrealist style, though it was painted ten years before the movement was “founded” by André Breton in 1924.

World War I brought an end to this phase but indicated the beginning of a number of anti-art movements, such as Dada, including the work of Marcel Duchamp, and of Surrealism. Artist groups like de Stijl and Bauhaus developed new ideas about the interrelation of the arts, architecture, design, and art education.

Modern art was introduced to the United States with the Armory Show in 1913 and through European artists who moved to the U.S. during World War I.

After World War II

It was only after World War II, however, that the U.S. became the focal point of new artistic movements.[15] The 1950s and 1960s saw the emergence of Abstract Expressionism, Color field painting, Conceptual artists of Art & Language, Pop art, Op art, Hard-edge painting, Minimal art, Lyrical Abstraction, Fluxus, Happening, Video art, Postminimalism, Photorealism and various other movements. In the late 1960s and the 1970s, Land art, Performance art, Conceptual art, and other new art forms had attracted the attention of curators and critics, at the expense of more traditional media.[16] Larger installations and performances became widespread.

By the end of the 1970s, when cultural critics began speaking of “the end of painting” (the title of a provocative essay written in 1981 by Douglas Crimp), new media art had become a category in itself, with a growing number of artists experimenting with technological means such as video art.[17] Painting assumed renewed importance in the 1980s and 1990s, as evidenced by the rise of neo-expressionism and the revival of figurative painting.[18]

Towards the end of the 20th century, a number of artists and architects started questioning the idea of “the modern” and created typically Postmodern works.Wikidata] (CIMA),[21] Kolkata

Iran

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Tehran

Ireland

- Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin

- Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin

Israel

- Tel Aviv Museum of Art

Italy

- Palazzo delle Esposizioni

- Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna

- Venice Biennial, Venice

- Palazzo Pitti, Florence

- Museo del Novecento, Milan

Mexico

- Museo de Arte Moderno, México D.F.

Netherlands

- Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

- Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

Norway

- Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Oslo

- Henie-Onstad Art Centre, Oslo

Poland

- Museum of Art, Łódź

- National Museum, Kraków

Qatar

- Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha

Romania

- National Museum of Contemporary Art, Bucharest

Russia

- Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

- Pushkin Museum, Moscow

- Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Serbia

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade

Spain

- Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Barcelona

- Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

- Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid

- Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Valencia

- Atlantic Center of Modern Art, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria

- Museu Picasso, Barcelona.

- Museo Picasso Málaga, Málaga.

Sweden

- Moderna Museet, Stockholm

Taiwan

- Asia Museum of Modern Art, Taichung

United Kingdom

- Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, London

- Saatchi Gallery, London

- Tate Britain, London

- Tate Liverpool

- Tate Modern, London

- Tate St Ives

Ukraine

- National Art Museum of Ukraine, Kyiv

- Andrey Sheptytsky National Museum of Lviv, Lviv

United States

- Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

- Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois

- Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Plaza Art Collection, Albany, New York

- Guggenheim Museum, New York City, New York, and Venice, Italy ; more recently in Berlin, Germany, Bilbao, Spain, and Las Vegas, Nevada

- High Museum, Atlanta, Georgia

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California

- McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, Texas

- Menil Collection, Houston, Texas

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts

- Museum of Modern Art, New York City, New York

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California

- The Baker Museum, Naples, Florida

- Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, New York

See also

- 20th century art

- 20th-century Western painting

- Art manifesto

- Art movements

- Art periods

- Conceptual art

- Contemporary art

- Gesamtkunstwerk

- History of painting

- List of 20th-century women artists

- List of modern artists

- Modern architecture

- Modernism

- Postmodern art

- Western painting

Notes

Sources

-

Arnason, H. Harvard; Prather, Marla (1998). History of modern art : painting, sculpture, architecture, photography (4th ed.). New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8109-3439-9. OCLC 1035593323 – via Internet Archive.

- Atkins, Robert (1997). Artspeak: A Guide to Contemporary Ideas, Movements, and Buzzwords (2nd ed.). New York: Abbeville Press Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7892-0415-8. OCLC 605278894 – via Internet Archive.

- Cahoone, Lawrence (1996). From Modernism to Postmodernism: An Anthology. Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-1-55786-602-8. OCLC 1149327777 – via Internet Archive.

- “CIMA Art Gallery”. Times of India Travel. 2015-06-30. Retrieved 2021-06-12.

- Clement, Russell (1996). Four French Symbolists: A Sourcebook on Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Maurice Denis. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-29752-6. OCLC 34191505.

- Cogniat, Raymond (1975). Pissarro. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-517-52477-0. OCLC 2082821.

- Corinth, Lovis; Schuster, Peter-Klaus; Vitali, Christoph; Butts, Barbara; Brauner, Lothar; Bärnreuther, Andrea (1996). Lovis Corinth. Munich; New York: Prestel. ISBN 978-3-7913-1682-6. OCLC 35280519.

- Greenberg, Clement (1982). “Modernist Painting”. In Frascina, Francis; Harrison, Charles; Paul, Deirdre (eds.). Modern Art and Modernism: A Critical Anthology. In association with the Open University. London: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-318234-9. OCLC 297414909 – via Internet Archive.

- Gombrich, Ernst H. (1995). The Story of Art. London: Phaidon Press Limited. ISBN 978-0-7148-3355-2. OCLC 1151352542 – via Internet Archive.

- Jencks, Charles (1987). Post-Modernism: The New Classicism in Art and Architecture. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0-8478-0835-9. OCLC 1150952960 – via Inernet Archive.

- John-Steiner, Vera (2006). “Patterns of Collaboration among Artists”. Creative Collaboration. Oxford University Press. pp. 63–96. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195307702.003.0004. ISBN 978-0-19-530770-2. OCLC 5105130725, 252638637.

- Lander, David (November–December 2006). “Fifties Furniture THE SIDE TABLE AS SCULPTURE”. Shopping. American Heritage. American Association for State and Local History. 57 (6). ISSN 2161-8496. OCLC 60622066. Archived from the original on 2007-10-20.

- Mullins, Charlotte (2006). Painting people : figure painting today. New York: D.A.P./Distributed Art Pubs. ISBN 978-1-933045-38-2. OCLC 71679906.

- Saunders, Frances Stonor (2013-06-14) [1995-10-22]. “Modern art was CIA ‘weapon’“. The Independent. Archived from the original on 2022-05-15. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- Scobie, Stephen (1988). “The Allure of Multiplicity: Metaphor and Metonymy in Cubism and Gertrude Stein”. In Neuman, S. C.; Nadel, Ira Bruce (eds.). Gertrude Stein and the Making of Literature. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-08541-5_7. ISBN 978-1-349-08543-9. OCLC 7323640453 – via Internet Archive.

Further reading

- Adams, Hugh (1979). Modern Painting. New York: Mayflower Books. ISBN 978-0-8317-6062-5. OCLC 691113035 – via Internet Archive.

- Childs, Peter (2000). Modernism. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-13116-9. OCLC 48138104 – via Internet Archive.

- Crouch, Christopher (1999). Modernism in Art, Design and Architecture. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-0-312-21830-0. OCLC 1036752206 – via Internet Archive.

- Dempsey, Amy (2002). Art in the Modern Era: A Guide to Schools and Movements. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-4172-4. OCLC 47623954.

- Everdell, William (1997). The First Moderns: Profiles in the Origins of Twentieth-Century Thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-22484-8. OCLC 45733213 – via Internet Archive.

See also: The First Moderns. - Frazier, Nancy (2000). The Penguin Concise Dictionary of Art History. New York: Penguin Reference. ISBN 978-0-14-051420-9. OCLC 70498418.

- Hunter, Sam; Jacobus, John M; Wheeler, Daniel (2005). Modern Art: painting, sculpture, architecture, photography (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-150519-3. OCLC 1114759321.

- Kolocotroni, Vassiliki; Goldman, Jane; Taxidou, Olga, eds. (1998). Modernism: An Anthology of Sources and Documents. Edinburgh; Chicago: Edinburgh University Press; The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-585-19313-7. OCLC 1150833644, 44964346 – via Internet Archive.

- Ozenfant, Amédée; Rodker, John (1952). Foundations of Modern Art. New York: Dover. ISBN 9780486202150. OCLC 1200478998. Retrieved 2021-04-19 – via Internet Archive.

- Read, Herbert Edward; Read, Benedict; Tisdall, Caroline; Feaver, William (1975). A Concise History of Modern Painting. New York: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-71730-8. OCLC 741987800, 894774214, 563965849 – via Internet Archive.

- Tate Modern

- The Museum of Modern Art

- Modern artists and art

- A TIME Archives Collection of Modern Art’s perception

- National Gallery of Modern Art – Govt. of India