Santa Fe: The Enigma of Uniform Architecture.. Between the Cohesion and Fabrication

Introduction: An Unexpected Encounter with a Color “Expert”

On a hot August afternoon, while strolling through a quiet neighborhood in Santa Fe, my peace was suddenly interrupted by a young man in work clothes, who asked in a straightforward local accent, “I need your help, brother… Is this color okay?” He was a house painter, holding his brush and staring anxiously at the wall he was painting. It took me a moment to realize he was serious; in a city dominated by earthy brown tones, his worry was that the color requested by the homeowner might be “too orange.” That moment was revealing; visual familiarity with this color homogeneity had turned the simple painter into a “expert” and visual critic, capable of discerning subtle differences invisible to the passing visitor.

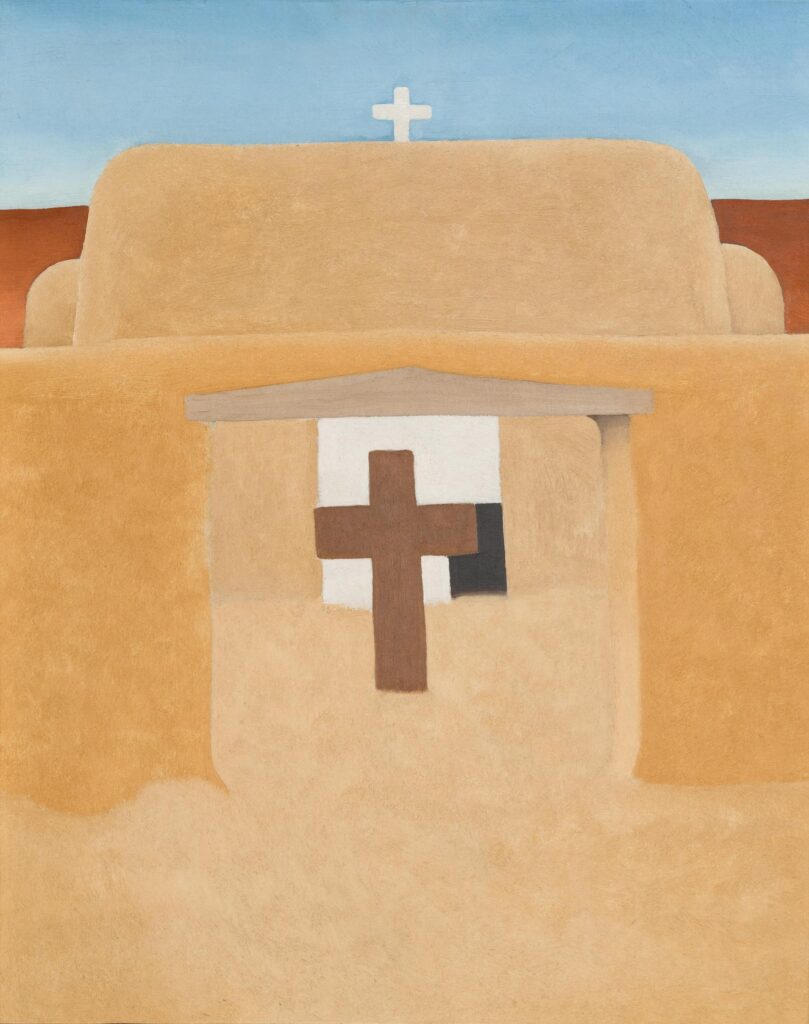

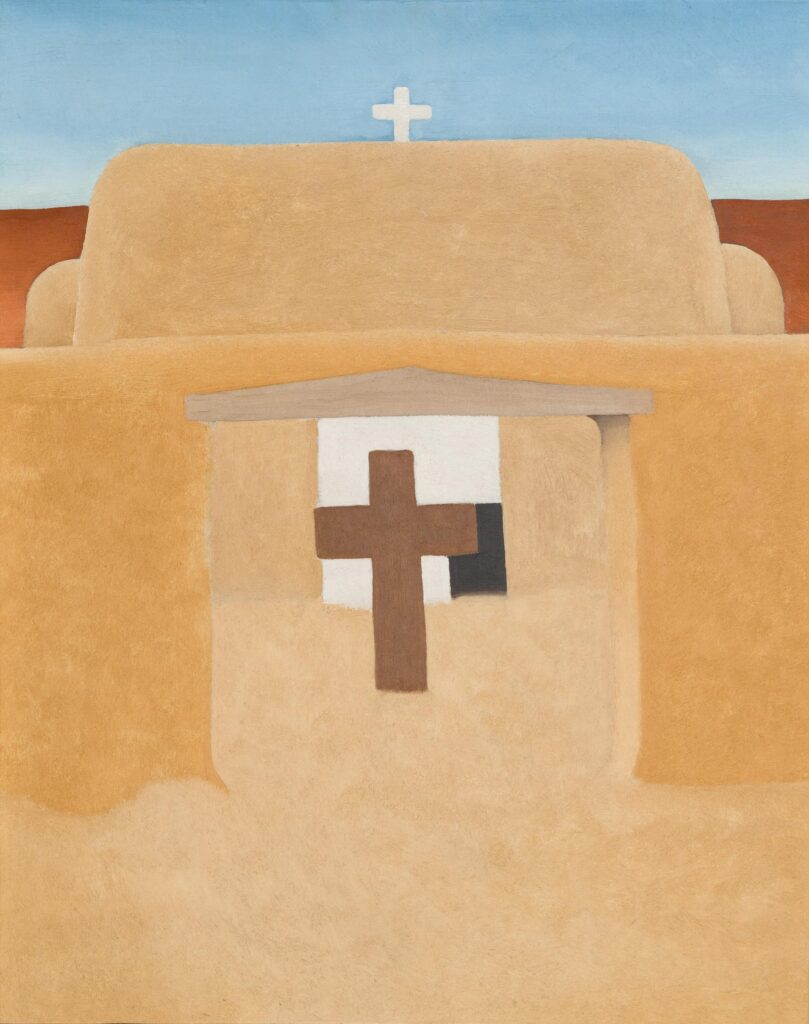

Santa Fe: A Vast Earthen Canvas of Architectural Cohesion

Few cities in the United States possess the stunning visual coherence of Santa Fe. This cohesion is due to the near-total dominance of the Pueblo Revival style on the urban landscape, from government and commercial buildings to residential homes, and even stores like Trader Joe’s. This style, with its thick earthen walls, stepped forms, and rounded corners, creates a sense that the city is carved from the earth itself. While some may see this homogeneity as monotonous, it gives Santa Fe a distinctive identity in an era of architectural globalization, where glass and steel skyscrapers have become a common language for cities like Riyadh, Manhattan, and Singapore.

La Fonda Hotel: The Archetypal Model of Pueblo Revival

For any architectural tourist visiting Santa Fe, the La Fonda on the Plaza remains the first and most important stop. The hotel represents the ideal model embodying all the hallmark features of the style:

· Stepped Massing and Rounded Corners: Directly mimicking historic Pueblo structures dating back centuries, like the majestic Taos Pueblo.

· Thick Earthen Walls: Often appearing to be made of adobe or something similar, with stucco used to replicate its raw appearance.

· Protruding Wooden Beams (Vigas): These beams are not merely decorative; they provide necessary visual variety that breaks the monotony of the simple facades, giving the building a distinctive character unlike many residential homes that lack this design prowess.

Policy and Legislation: Engineering by Law

Behind this unified scene lies a more surprising story. The “old-style” identity of Santa Fe is actually an invention of the twentieth century. The city’s current style was enforced through municipal ordinances, most notably the 1957 ordinance drafted by a committee led by architect John Gaw Meem IV. This decree mandated that all new buildings in the historic district be built in the “Old Santa Fe Style,” defined as “the so-called Pueblo-Spanish, Spanish-Indian, and Territorial styles.” In other words, the visual coherence we see today is not the product of purely organic evolution but the result of deliberate planning policy.

Isaac Rapp: The Architect from New Jersey Who Designed the Southwest’s Identity

The paradox is complete when we delve into the origin of this style. The credit for framing and codifying the Pueblo Revival style goes to architect Isaac Rapp, who designed the current version of the La Fonda hotel in 1922. Strangely, Rapp was not from the Southwest; he was from Orange, New Jersey, and received his professional training in Illinois. Thus, the “authentic regional style” of Santa Fe is, in reality, an interpretation and execution of local motifs by an outside architect. This fact opens the door to deeper contemplation about the concept of “authenticity” in architecture and whether geographical roots are a prerequisite for creating a genuine architectural identity.

Loretto Chapel: A Gothic Gem in the Heart of the Desert

Amidst this prevailing landscape of earth and clay, a stunning exception stands out: the Loretto Chapel. This modestly sized chapel, said to be the first Gothic structure built west of the Mississippi (completed in 1873), proves that distinction doesn’t need to be loud. Built from locally quarried sandstone, it allowed the chapel to blend with its earthy surroundings while retaining its clear Gothic identity with its buttresses and stained-glass windows. Its beauty stems from this delicate balance; it does not starkly deviate from its environment, yet it allows the viewer to appreciate genuine architectural details, which might be difficult in a visually crowded environment.

The Miraculous Staircase: Where Legend Meets Engineering

Inside the chapel lies one of Santa Fe’s most famous landmarks: the Miraculous Staircase. Legend has it that the nuns of the chapel needed a staircase to access the choir loft. After nine days of prayer, a mysterious carpenter appeared, built this astonishing spiral staircase from wood not found in the region, used no nails or central support, and then disappeared without accepting payment. In its original design, the staircase appeared to float without a railing, like a surreal link between earth and sky. This story reminds us that great architecture can be born from mystery and faith, not just from laws and decrees.

Conclusion: Architecture is a Choice, Not a Destiny

The architectural story of Santa Fe offers an important lesson for urban planners and architects alike. The coherent urban landscape we see today, which seems “natural” and inevitable to the visitor, is actually the product of a series of conscious decisions: the decision of an architect from New Jersey to adopt and develop a local style, and the decision of a municipality to enforce this style by law. This does not diminish the value of Santa Fe’s beauty but adds a new dimension to it; it proves that our cities are merely a reflection of what we decide to build. In a world where cities are becoming similar, Santa Fe reminds us that identity is a choice, and that beauty can emerge even from rigid decisions, as long as they stem from a clear vision.

✦ Archup Editorial Insight

The article examines the formation of Santa Fe’s cohesive architectural identity through the legally enforced Pueblo Revival style, highlighting the contrast between the style’s fabricated origins and its organic appearance. The analysis reveals that this imposed homogeneity acts as a constraint on the organic evolution of the local architectural language, where the external form is mimicked instead of fundamentally developing original building techniques and materials, resulting in a museum-like environment lacking design vitality. The model relies on reproducing stepped masses and earthwork facades without deeply addressing the relationship between interior spaces and the harsh desert climate or the needs of contemporary life. On the other hand, the strict regulatory framework has successfully protected the city’s unique urban character from visual chaos and prevented deviation from the local identity amidst the pressures of globalization.

Brought to you by the ArchUp Editorial Team

Inspiration starts here. Dive deeper into Architecture, Interior Design, Research, Cities, Design, and cutting-edge Projectson ArchUp.

🚫 Very important note: Please be careful not to add any links to old jobs within the article content.