The House of a Lifetime: Between Wisdom, Wealth, and the Web of a Spider

A few weeks ago, during a family gathering, I found myself sitting beside a man whose reputation precedes him.

A poet, a scholar, and a figure well known enough to have his own Wikipedia page.

He spoke with the calm tone of someone who had long stopped competing with the world.

He was comfortable, content, and quietly complete.

As we spoke about life, I asked him almost naturally about his home.

“How long have you lived there?” I said. “Is it your own design?”

He smiled and answered with the modesty of a man who no longer measures himself by what he owns.

Later that evening, as we left, one of my relatives told me something that lingered.

He said that this same poet once received sixty thousand dollars a substantial sum and rather than invest it, he spent it on a three-month family trip around the world.

When a friend of his, a businessman, questioned the decision, the poet replied with a proverb passed down from his grandfather:

“اللي حيموت ما حيكون عنده أكثر من بيته العنكبوت”

“He who dies will own nothing greater than the house of a spider.”

A line poetic in its humility, devastating in its realism.

The Architecture of Philosophy

That phrase stayed with me.

Because behind its humor lies a philosophy that shaped generations before us the belief that permanence is an illusion, that wealth should be lived, not stored.

Yet today, when we revisit that idea through the lens of economics, it raises a sharper question.

If that same sixty thousand dollars had been spent on land forty years ago, in a prime location, it might now be worth 1.6 million dollars or more.

The trip would have ended, but the property would still be there rising in value even as its owner aged.

So who was right?

The poet who chose memory, or the investor who chose legacy?

The Generational Divide

The generation that said “بيت العنكبوت” lived in a time of stability and slower inflation.

Property then was not just expensive it was distant.

Families lived where they worked. Dreams were smaller.

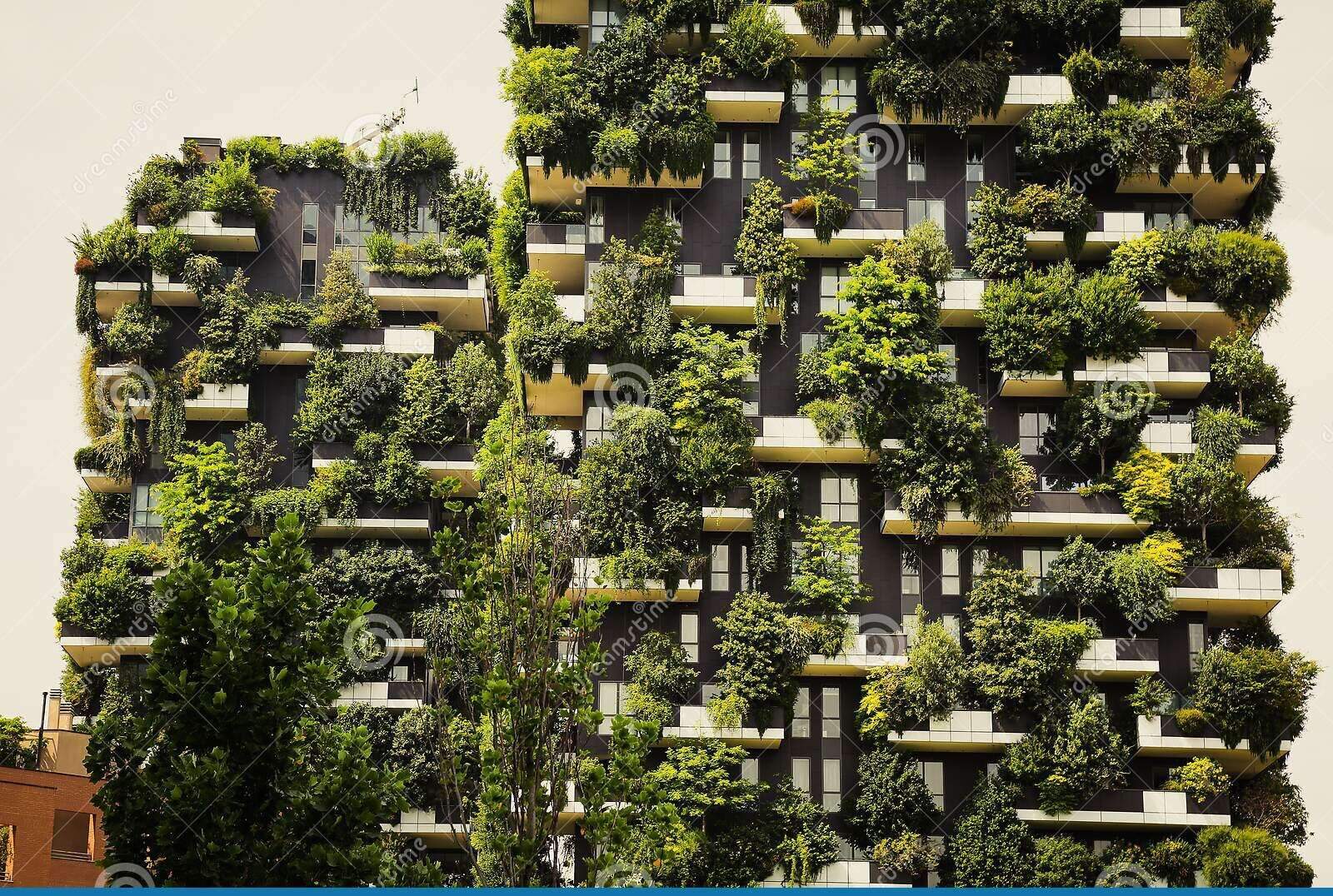

But the generation after them, the one building architecture today, lives in a world where space equals security.

Owning a home is no longer just shelter. It is identity, collateral, and inheritance.

When a parent today buys land, they are not only building walls but buying time protection from volatility, rent, and uncertainty.

The poet’s decision made sense in his era, but architecture, like life, evolves with its economics.

When Wisdom Ages

The question is not whether he was wrong.

It is whether the context changed.

He traded his sixty thousand dollars for joy, laughter, and stories.

But his children now face a different equation one where joy is short and property is distant.

To build a home today is not vanity. It is necessity.

To travel is still beautiful, but the earth beneath your name gives you something the world cannot: permanence.

The Spider’s House Revisited

The old proverb lives on because it holds a paradox.

Yes, when we die, we leave everything behind.

But while we live, we need a structure to hold our existence not only spiritually, but physically.

A spider’s web may be fragile, yet it is the only home it has.

And perhaps that was the poet’s hidden meaning: it is not the size of the house that matters, but the purpose it serves.

Maybe both generations are right.

The poet built moments. The architect builds memory.

Each in his own way is trying to resist the same truth that time, not money, is the real developer.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

In “The House of a Lifetime: Between Wisdom, Wealth, and the Web of a Spider”, the essay meditates on the lifelong pursuit of a perfect home, weaving together cultural metaphors, personal ambition, and architectural longing. The descriptive flow powerfully evokes how the idea of home evolves—shaped by economics, ego, and aging wisdom. While the metaphor of the spider’s web is conceptually rich, the piece could benefit from clearer spatial anchors or urban case studies to ground its philosophical musings in built reality. Looking a decade ahead, as generational wealth shifts and digital nomadism rise, the notion of a “forever home” may become more symbolic than structural. Still, the article poignantly highlights how a house is not only constructed in concrete and stone, but also layered in memory, identity, and dreams.

So when someone asks, “What is your house worth?”

Maybe the answer should be: it depends whether you measure it in square meters or in stories.