There is no doubt that capital-S Sustainability has lost some of its polish in the last few years. Greenwashing, a term coined in 1986, is now so identifiable as a “thing” that it has its own Wikipedia page. Advocates of Sustainability now have to be more cautious in their claims: A dull realism has set in. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs notes that because “so many of the components of existing economic systems are ‘locked into’ the use of non-green and non-sustainable technologies,” the bar is not going to move anytime soon.

And yet, Sustainability remains a worthy goal. After all, we have to at least try to make our buildings and cities more in line with the science of global warming, even if it amounts to playing Mozart while the Titanic is sinking. Part of the problem is that the building industry has bought into the lingo, as have many clients, with little in the way of serious changes.

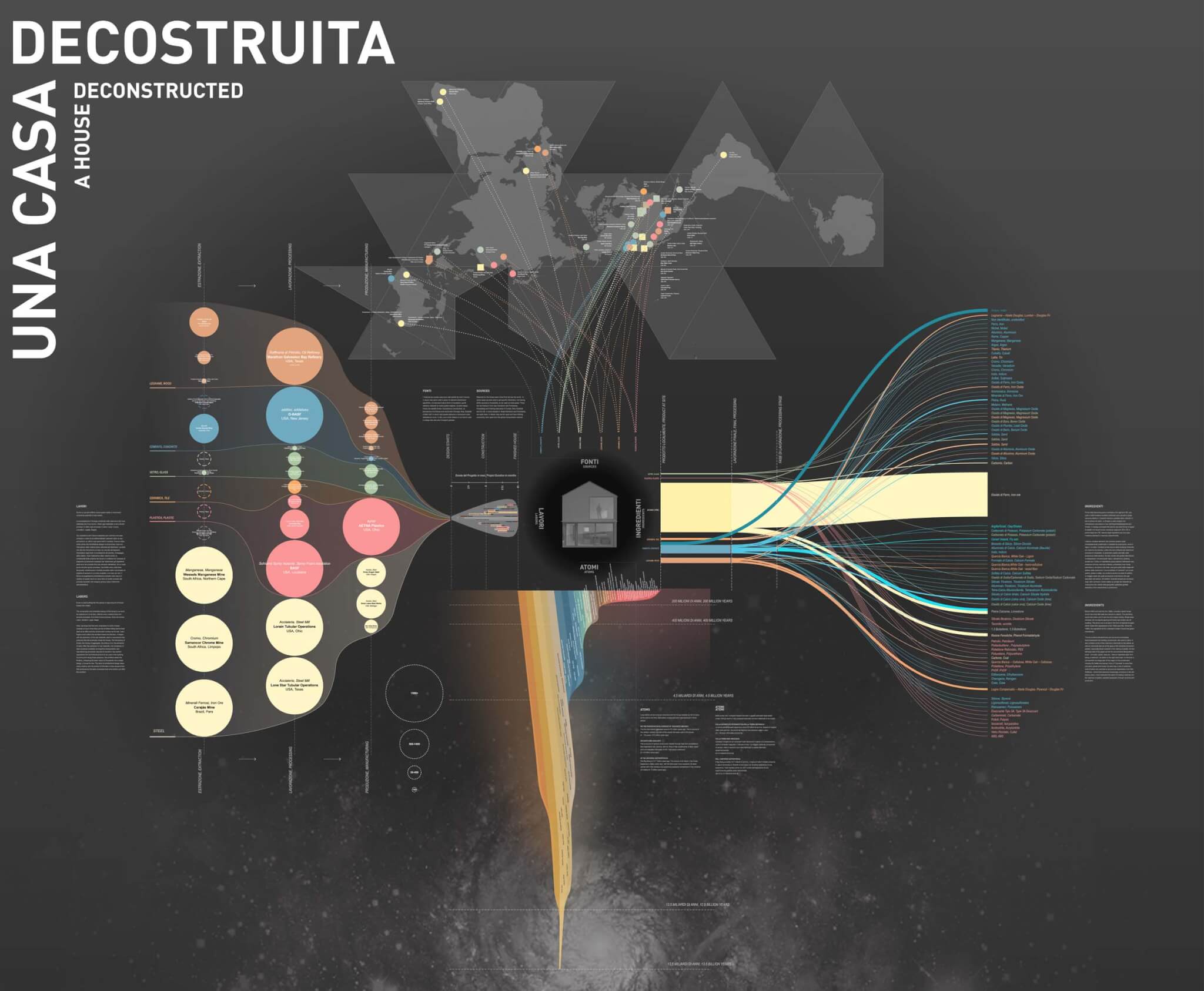

Vikramaditya Prakash and I, in our Office of (Un)Certainty Research, spent three years studying a recently built house in Seattle, a modest modernist house that was designed around all the issues of Sustainability. The architect graciously let us into the inner workings of the process and agreed to be interviewed along with the other designers, contractors, and builders involved. We studied the building from four perspectives: its labor history, its mining history, its chemical history, and its atomic history. The main lesson we learned was that because of increased chemicalization of building components in the last 20 or 30 years, the building’s ecological footprint is fully global. Furthermore, much of this chemicalization was done in the name of Sustainability. (The results of our research were presented during the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2021 and in the book A House Deconstructed, published by Actar.)

My house in the Boston area, by way of contrast, was built in 1900 with no plastics. It also originally had little metal apart from the nails, cast-iron sewage pipes, and copper water pipes. Its foundation was made of fieldstone. The plate glass for the windows was the most expensive item and probably came from Pittsburgh.

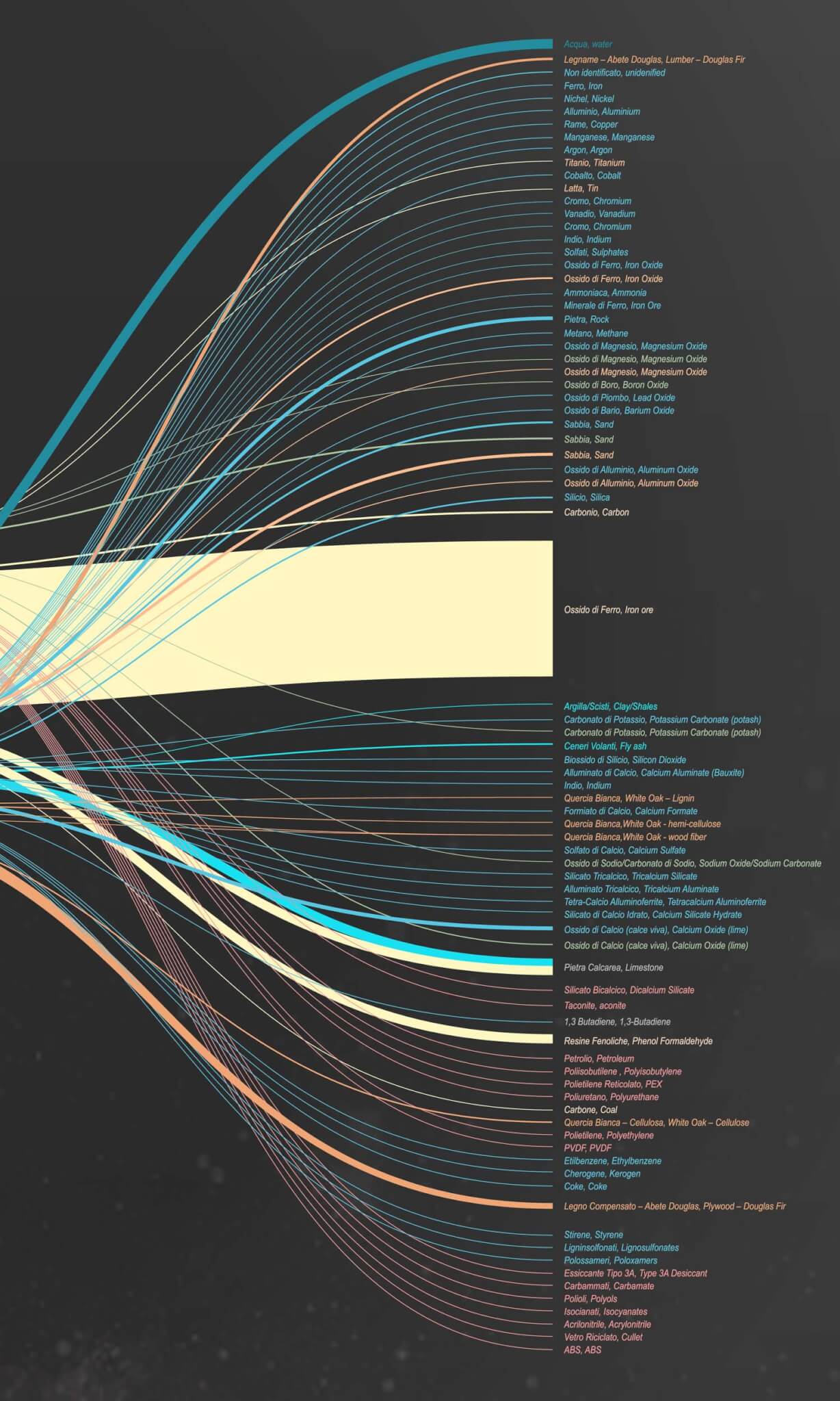

The Seattle house was a different creature altogether. It used metal in the cladding, structure, framing, and detailing. There were dozens of special high-end additives and coatings, even for the concrete. The more we studied the building, the longer and longer the “ingredients list” became. The glass, through the addition of zinc stearate and barium nitrate, for example, had been developed in recent years, the same too for the concrete and steel. This chemicalization improves the life span of the material or adds strength, but the downside is that the chemicals had to come from somewhere. They had to be mined and processed, and many are toxic.

The glass has a particularly interesting story. It was made in a factory in Minnesota, in a region where huge sand strip mines scour the earth. Mining companies are there to secure high-priced sand to be used in fracking. All the other sand that is processed, about 95 percent of it, is more or less discarded and bought by glass companies clustered around the area. Glass is now the cheapest architectural surfacing material. No wonder it’s everywhere.

The ecological damage of sand mining and the human cost to locals who breathe the particles—plus the fact that the glass is fabricated completely by robots—almost never make it into architectural conversations and are certainly never brought up in architectural schools. Multiply this hundreds of times across the planet—think of the cobalt mines in the Congo, the zinc mines in China, the barite mines in Nevada, the witherite mines in Tasmania, and on and on—and we quickly get to see the incredible “reach” that the building industries have.

We have few tools with which to trace these supply chains. The plastics industry is particularly opaque, and so too steel sourcing. Recycled steel, as was used in the Seattle house, gave the owner and architect a good feeling, but the recycling process mostly happens in Bangladesh, India, and Turkey and has produced vast contamination zones with huge human costs. Alas, out of sight, out of mind.

Though there are some trying to incite change, the building industry continues to scratchproof its messaging. Without more interest from architects, there is little to stop this portion of the global economy from constructing its own positive spin while the time remaining to change slips away.

In order to bring these conversations into the open, it seems the main point of attack will have to come from academia. Hopefully courses, seminars, and workshops will be developed that teach future architects to see these broader pictures and make more-informed decisions.

Mark Jarzombek is a professor in the Department of Architecture at MIT.