A Century of American Life: The Silent Architecture of Behavior

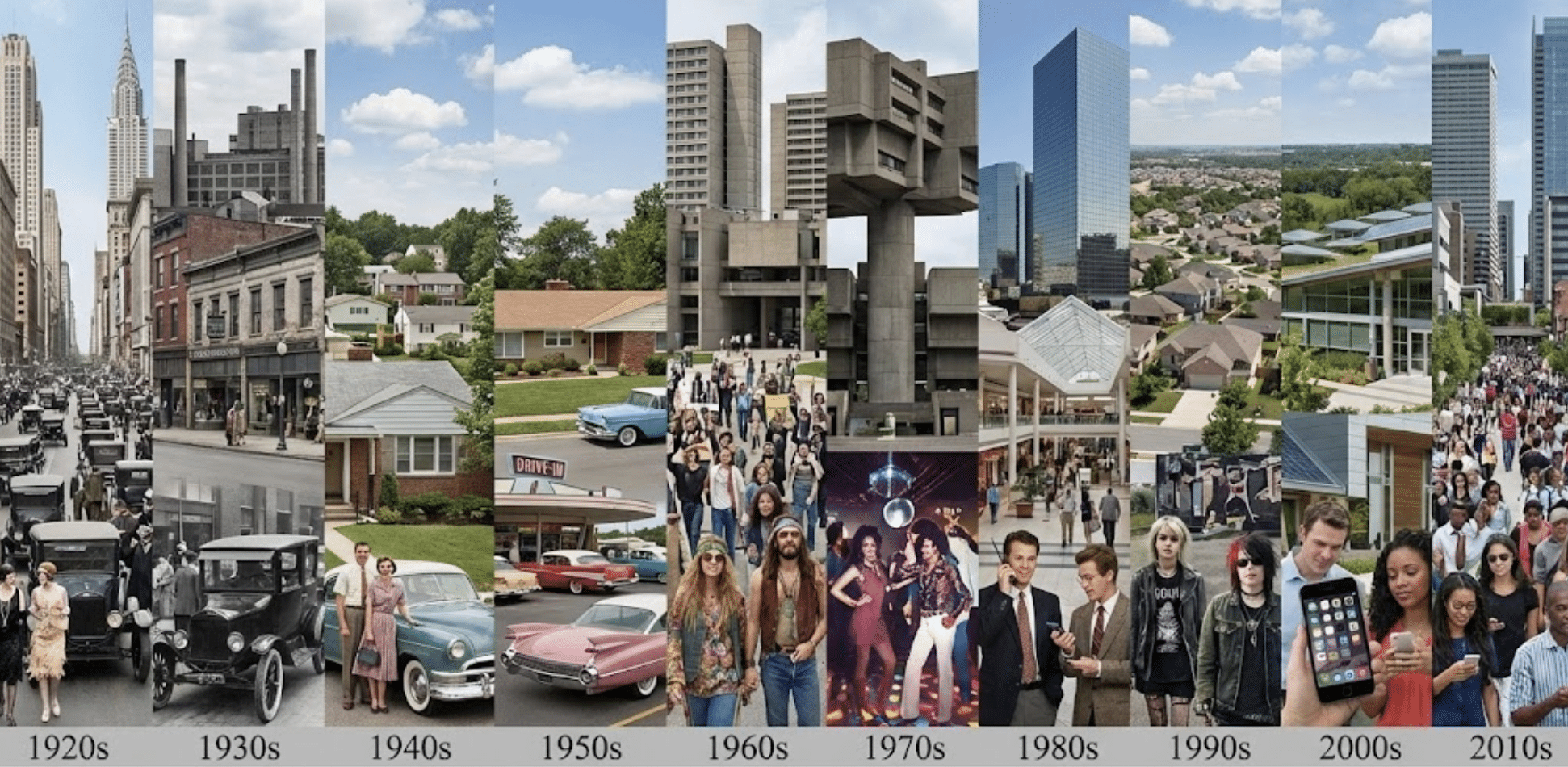

America did not change in sudden, tectonic shifts. It evolved quietly, almost imperceptibly, through the introduction of ordinary objects that slowly redefined the rituals of how people lived, moved, ate, and gathered. To the observant critic, Architecture was rarely the protagonist in this century-long transformation; often, it was merely the container, a lagging indicator that adapted, struggled, or expanded to accommodate the changing demands of daily life. To understand the built environment of today, one must look past the skyscrapers and into the mundane habits of the past hundred years, tracing how culture and technology conspired to rewrite the spatial logic of the nation.

What often escapes non-American readings of architecture is how deeply the built environment became an extension of a specific lifestyle ideology rather than a neutral response to climate or density. The detached house, the private car, and the suburban plot were not accidental outcomes but deliberate spatial instruments of a middle-class dream engineered after World War II. By the 1950s, homeownership in the United States surpassed 60 percent, driven by federal mortgage policies, highway expansion, and mass-produced housing models that treated land as abundant and mobility as guaranteed. The automobile did not merely connect spaces; it reorganized daily life around distance, consumption, and personal autonomy, turning the garage into a primary architectural feature rather than a secondary utility. Suburbia emerged as a spatial promise of safety, predictability, and upward mobility, where retail followed housing, not the reverse, and where architecture served consumption as much as shelter. This model normalized excess square footage, repeatable typologies, and an architecture calibrated for appliances, parking, and constant replacement. Understanding American architecture, therefore, requires reading it less as a stylistic evolution and more as a physical manifestation of an economic system where growth, convenience, and individual choice became the dominant design parameters.

The Roaring Consumption of the 1920s The 1920s marked the precise moment when mass consumption ceased to be a mere economic activity and solidified into a cultural identity. As the automobile transitioned from a luxury toy to a prosthetic extension of personal freedom, it began to dictate the geometry of the street itself. Simultaneously, the rise of the department store transformed downtown cores into cathedrals of display, where the act of purchasing was elevated to a public spectacle. This era planted the seeds for a commercial typology where buildings were no longer just functional shelters but performative stages for a society increasingly obsessed with visibility and leisure.

The Aerodynamic Dreams of the 1930s Despite the crushing economic weight of the Great Depression, the 1930s birthed a radical hybrid of mobility and entertainment that would forever alter the American landscape: the Drive-in. This was not merely a cinema; it was a total reconfiguration of land use where the car dashboard replaced the living room hearth. The industrial obsession with speed influenced Building aesthetics, favoring horizontal lines and aerodynamic curves that suggested motion even when standing still. Urban leisure detached itself from fixed locations, becoming fluid and inseparable from the vehicle itself.

The Industrialized Efficiency of the 1940s War has a way of reorganizing civilian life, and the 1940s brought the logic of the factory into the home. Efficiency became the supreme virtue, birthing the “McDonald’s model”—an architectural machine designed solely for the rapid distribution of calories. Domestic spaces followed suit; the kitchen was reimagined not as a place of warmth, but as an optimized production zone, prioritizing workflow over comfort. This era introduced a systemic way of thinking that echoed the industrial logic which would later define modern Construction methodologies, valuing repeatability over uniqueness.

The Electronic Hearth of the 1950s Perhaps no single object reshaped the geometry of domestic life more profoundly than the television. In the 1950s, the living room ceased to be a space for face-to-face conversation and transformed into a darkened theater focused on a glowing box. Furniture was reoriented, the fireplace lost its status as the focal point, and the home turned inward. This shift fueled the horizontal explosion of the suburbs, driven by appliance-heavy kitchens and a desire for isolated leisure zones, effectively birthing the modern concept of media-centric Interior Design.

The Disposability of the 1960s By the 1960s, convenience had become the ultimate cultural currency. The introduction of frozen meals and modular technologies ushered in an era of “disposability” that bled into the built environment. As cooking was condensed by technology, kitchens shrank in size but grew in density. This culture of impermanence mirrored a shift in Cities, where buildings began to be viewed less as permanent monuments and more as temporary commodities, subject to the same cycles of obsolescence as the products consumed within them.

The Rebellion of the 1970s The 1970s arrived as a reaction against the rigid order of the preceding decades. As cultural norms loosened, architecture flirted with informality. The rigid parlor gave way to the “conversation pit” and open-plan living, rejecting the strict compartmentalization of the mid-century home. Public spaces became expressive arenas for counterculture and identity politics, blurring the once-clear boundaries between formal architecture, Design, and social expression.

The Surface Culture of the 1980s With the arrival of the 1980s, video games entered the home and bold color returned with aggressive confidence. Architecture responded with Postmodernism, transforming buildings into communicative signboards rather than silent functionalist boxes. Dedicated entertainment rooms emerged as distinct zones, while furniture design prioritized visual impact and media consumption over ergonomic tradition, reflecting a decade deeply invested in surface and image.

The Dissolution of Boundaries in the 1990s The 1990s quietly prepared the ground for the “death of distance.” The introduction of the internet and early mobile devices began to fracture the rigid separation between “work” and “home.” The home office emerged as a necessary hybrid zone, and wireless technology began to alter spatial behavior, reducing human dependency on fixed locations. This period signaled the beginning of today’s urgent Architectural Research into hybrid environments, where the physical and digital worlds begin to overlap.

The Invisible Infrastructure of the 21st Century In the current era, the smartphone and the cloud have fundamentally redefined ownership and proximity. We no longer require physical storage for music, books, or media; the bookshelf has been dematerialized. Homes have transformed into logistical hubs for delivery and digital consumption. Buildings now operate as active platforms rather than static containers, intersecting directly with the critical discourse on Sustainability and smart efficiency, where data is as crucial a material as concrete.

A Speculative Horizon: 2050 Looking toward 2050, it becomes clear that architecture will no longer be defined by form, but by adaptability. We are moving toward a future of temporal living, where homes are designed for flux rather than permanence, and where the reduction of private car ownership will allow cities to reclaim vast tracts of land for public use. The future suggests a return to architecture as a responsive framework—a system rather than a symbol.

The Death of Function and the Rise of the Algorithm

For a century, Louis Sullivan’s mantra “Form Follows Function” ruled the architectural academy. Today, we are witnessing the quiet death of that maxim. In the era of the ubiquitous screen, “function” is no longer tied to a specific room. We work in bed, watch cinema on the toilet, and socialize in the kitchen. Architecture is no longer about designating spaces for specific tasks; it is about providing a flexible, high-bandwidth canvas for the Algorithm. The architect of the future is not a shaper of rooms, but a designer of “possibilities,” where the walls matter less than the Wi-Fi signal, and the furniture matters less than the camera angle for the video call. We have moved from Le Corbusier’s “Machine for Living” to the “Platform for Broadcasting.”

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how American socio-economic ideologies were translated into a built reality, evolving from the Neoclassical rigor of federal institutions to the Mid-Century Modernism of post-war suburbia. It analyzes how the “American Dream” institutionalized spatial privacy and automobile dependency as fundamental components of the Urban Fabric. However, the core architectural critique questions the long-term Sustainability of this model; while it successfully exported material prosperity, it imposed a consumerist typology that diluted Contextual Relevance in many global cities, replacing local identity with homogenized, repetitive forms. Despite this cultural alienation, the American experience remains a vital study in Functional Resilience, demonstrating an unparalleled ability to reinvent the meaning of “home” in alignment with continuous technological and lifestyle shifts.