American Decoration: How a Nation Turned Its Lifestyle into Global Architecture

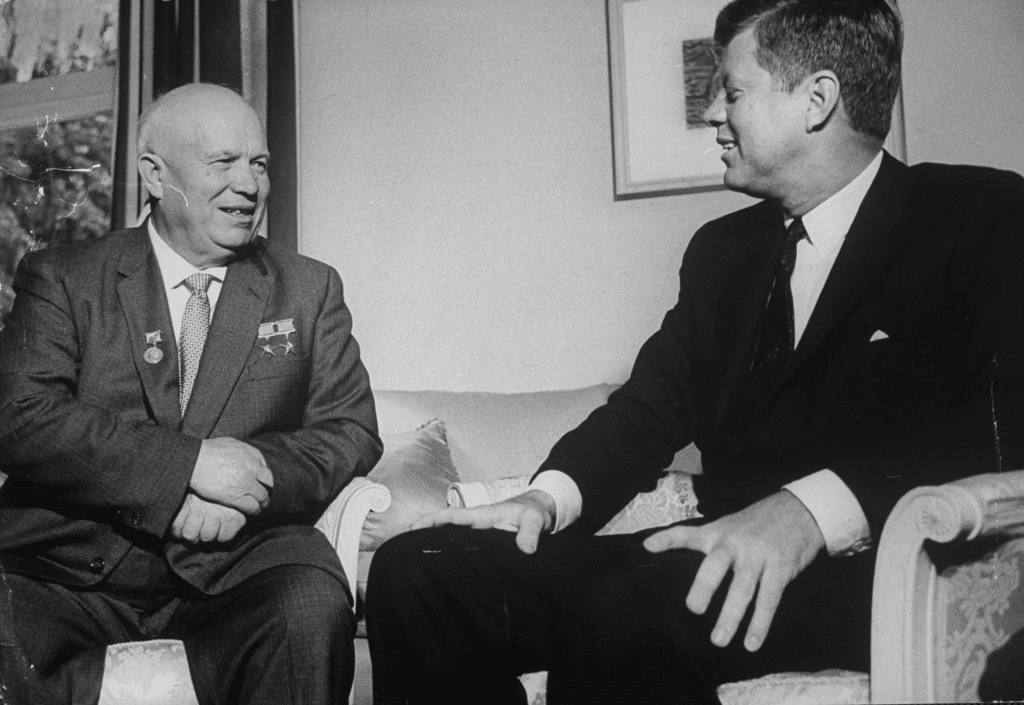

There is a small but unforgettable moment in the history of the Cold War, a moment that belongs less to geopolitics and more to the strange power of architecture. During a diplomatic exchange between President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, an American official delivered a line that cut deeper than any nuclear doctrine. You do not need propaganda. You already have the world because everyone wants your kitchens. Everyone wants your bathrooms. No one dreams of living in a Soviet apartment.

The statement was not about appliances. It was about desire. It was about space. About the quiet war that happened inside homes rather than across borders. If we look carefully, we realize that the aesthetic, spatial, and material DNA of today’s global architecture was set in motion more than eighty years ago, shaped by the American lifestyle that emerged after World War II. The world did not simply import Hollywood movies. It imported American rooms.

This essay examines how American everyday life transformed into a global architectural language, and why this influence still defines our cities, interiors, and spatial expectations. For readers who want broader architectural context, the evolving debates and research threads around cultural identity and the built environment are always accessible across the Architecture section at ArchUp at https://archup.net/architecture/ and through our expanding Research library at https://archup.net/architectural-research/.

The Cold War Kitchen: When Domestic Space Became Diplomacy

The world remembers missiles, treaties, and iron curtains. Yet architects remember the kitchen. The 1959 Kitchen Debate between Khrushchev and Vice President Richard Nixon exposed a hidden battlefield. Before journalists, cameras, and startled Soviet visitors, the American kitchen became the weapon that defeated ideology. It was efficient, cheerful, mechanically advanced, and psychologically engineered to promise a better life.

The Soviet response was defensive. The American position was confident. And architecture, quietly, became soft power.

It is impossible to understand modern global interiors without returning to this moment, because the model that America showcased did not remain American. It became universal. When you walk through a luxury tower in Dubai, a suburban villa in Riyadh, or a condo in Singapore, you are moving inside a descendant of the Cold War kitchen.

This cultural contagion is precisely what makes architectural news such as the projects featured in our Architecture News section at https://archup.net/news/ continually relevant. Architecture has never been neutral. It has always been loaded with ideology.

Post-War Consumerism and the Birth of the Made-in-America Home

After World War II, the United States developed a manufacturing ecosystem that was unmatched in scale and imagination. Companies like General Electric, Formica, and countless regional factories produced a universe of domestic goods: refrigerators, dishwashers, pastel-colored cabinetry, chrome handles, vinyl floors, modular closets, air conditioning, and lighting systems that looked as if they were designed for a spacecraft rather than a home.

Magazines such as Better Homes & Gardens became cultural bibles. The suburban boom created the Ranch House and the Split Level House, two typologies that still shape real estate patterns worldwide. When millions of American families moved into these new homes, they created a powerful image of modern domestic life. The world watched through cinema, TV, print, and eventually the internet.

To understand just how deeply this influence spread, one only needs to browse the Interior Design resources on ArchUp at https://archup.net/design/interior-design/ and compare global living spaces today with American originals from the 1950s and 60s. The resemblance is not coincidental. It is genealogical.

1967 and the Turn to American Ornamentation

By the late 1960s, the United States experienced a new wave of decorative expression. Plastic entered the scene. Pop colors took over. Patterned wallpapers, orange kitchens, avocado bathrooms, and chrome accents defined the era. It was a new chapter in American domestic identity, informed by mass production, optimism, and a unique cultural engine that blended Hollywood, advertising, and manufacturing.

Films of the era captured this aesthetic, including the spirit of what many refer to as American Decoration from the mid sixties. These represented a shift from minimalist European traditions to something louder and more democratic. American ornamentation was not elite. It was popular. It was accessible. It democratized beauty and united millions under one visual language.

This shift influenced every category of design, which you can trace in contemporary discussions across Design at https://archup.net/design/ and Building Materials at https://archup.net/building-materials/. Materials such as vinyl, acrylic, aluminum, and fiberglass became global not because of industrial superiority but because America exported a dream.

The Global Spread of American Domestic Space

To understand the power of American interiors, we must follow their journey around the world.

Japan, post World War II:

American occupation introduced new housing prototypes, appliances, and spatial standards. The Japanese kitchen evolved rapidly, blending local efficiency with American modularity.

Germany, post war reconstruction:

Marshall Plan funding brought not only infrastructure but American domestic ideals. Prefabricated kitchens, suburban planning, and a fascination with modern appliances all grew from this cultural exchange.

The Middle East during the oil boom:

From Riyadh to Dubai, American-style villas became the aspirational model. Wide kitchens, pantries, open-plan living rooms, and integrated appliances became indicators of modernity.

Today, as we analyze global architecture through the Cities lens at https://archup.net/cities/ or explore major Projects listed at https://archup.net/projects/, the same American spatial DNA keeps appearing. The world did not simply admire America. It internalized America.

Why the American Room Still Wins

There is a psychological reason behind the enduring appeal of American interiors. The American room is designed around comfort, clarity, and daylight. It favors wide circulation routes, horizontal flow, and intuitive zoning. The American kitchen, for instance, is built around movement. The triangle of sink, refrigerator, and stove was engineered for efficiency and remains a global standard.

American bedrooms are generous, closets are abundant, and living rooms are social rather than ceremonial. There is a cultural warmth embedded in the space. It promises ease, relief, and the constant possibility of a better life.

The Soviet room, by contrast, was engineered for survival. The Italian room was designed for craftsmanship. The Japanese room for ritual. But the American room was designed for aspiration. In a global culture obsessed with convenience and mobility, aspiration always wins.

Those interested in broader sustainability considerations can explore our evolving topics in Sustainability at https://archup.net/sustainability/ to see how American comfort has influenced ecological design debates today.

Eighty Years Later: The Continuum of Influence

Eighty years have passed since the blueprint of the modern American home began. Yet the influence remains intact. Even minimalism today is often an American reinterpretation, spread through Silicon Valley offices and global retail stores. Instagram, Pinterest, and TikTok have become new vectors of the same aesthetic empire.

The continuity is astonishing. Architects designing in 2025 are still working inside a mental map drafted before the Cold War. Even in contemporary competitions listed on ArchUp at https://archup.net/competitions/, submissions often echo American spatial logic: open plan kitchens, bright interiors, and modular systems.

This is not failure. It is the cultural gravity of a superpower.

A Question of Identity: What Happens When One Style Dominates the World

But we must ask a harder question. What happens when a single architectural style becomes the global default? What is lost when nations adopt American kitchens, American bathrooms, American spatial expectations, and American decorative instincts?

Identity weakens. Variation collapses. Cities begin to resemble one another. Local domestic traditions become secondary to global benchmarks of comfort.

The world gained practicality. It lost diversity.

This is where the role of critical editorial voices, including the perspectives from our Editors Team at https://archup.net/editors/, becomes essential. Architecture must not become a single script. It must remain a tapestry.

Toward a New Theory of Cultural Space

The purpose of this essay is not to criticize American architecture. It is to understand it. To understand how a nation exported its lifestyle and quietly reshaped the world. To understand how interior decoration in 1967 turned into a universal visual code. And to understand that culture does not vanish. It migrates.

As architects, writers, and thinkers, our task is to reclaim the local without denying the global. To design spaces that respect the American contribution while rebuilding the spatial soul of each nation.

Readers interested in tracing earlier reflections can explore the Article Archive at https://archup.net/archive/ and the foundational About ArchUp page at https://archup.net/archup-about/ for our broader architectural philosophy.

Architecture is not the shape of walls. It is the shape of human longing. And for eighty years, the world has longed for the American room. But longing is not destiny. It is a beginning. The next chapter belongs to those who study history carefully enough to rewrite it.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

“American Decoration” dissects a forgotten yet visually assertive moment in architectural history—the ornate visual language of mid-century American suburbia. Through the lens of a 1967 decorative trend, the article captures a transitional phase between traditional ornament and modern minimalism. The description is compelling, evoking nostalgia and a tactile memory of metal screens, textured façades, and saturated palettes. However, the article could benefit from a more critical stance: How did these aesthetics contribute to cultural narratives of class, race, or aspiration? In a future context, this piece may gain value as a reference point for postmodern revivalists or visual anthropologists examining how style encodes ideology. As we navigate contemporary design debates, revisiting such decorative episodes reminds us that what we dismiss as kitsch may hold the keys to understanding an era’s psyche.