Operational Architecture: Office and Transit Hubs in Tokyo and Sydney 2026

Operational architecture is reshaping how design interacts with urban movement. A growing debate in Japan and Australia questions how far architecture should steer daily behavior. In 2026, buildings no longer just house activities. They function as dynamic systems that manage human flow, boost efficiency, and redefine use evident in two distinct yet aligned models: Tokyo and Sydney.

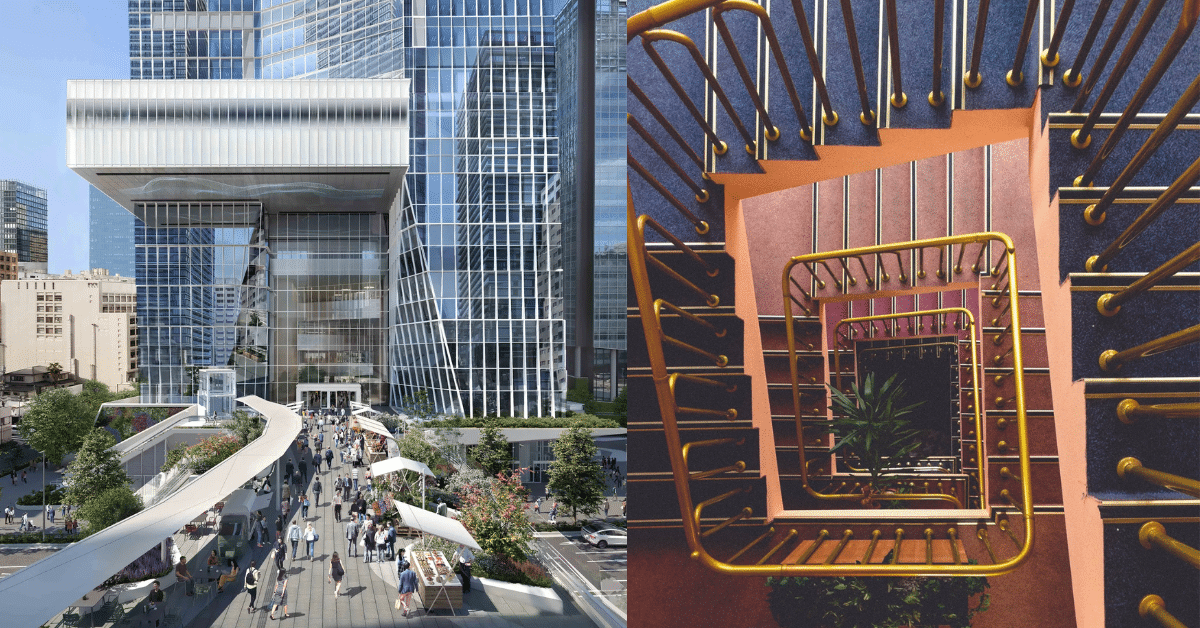

Vertical Urban Models in Tokyo

Tokyo’s urban planning now centers on multi-level infrastructure tightly linked to public transit. These Transit Oriented Development projects integrate train stations with commerce and go further. They treat the building itself as a complete urban unit. Transport, offices, retail, services, and walkways merge into one vertical structure that runs nonstop.

This model favors vertical density over horizontal spread. It separates pedestrian, vehicle, and logistics flows onto distinct levels. The result reduces conflicts and improves operational performance. Facades act less as aesthetic statements and more as functional interfaces. They regulate daylight, ventilation, and movement.

Operational architecture now manages time and movement, not just form.

Planners measure success by shorter commutes, higher transit use, and smooth peak hour operations. Architectural design decisions now tie more closely to infrastructure and urban economics than to visual identity.

Behavior Steering Within Buildings in Sydney

Sydney applies a similar logic at a smaller scale. Instead of reshaping the city, it guides behavior inside individual buildings. Several office buildings opened in early 2026 make stairs more visible and accessible than elevators. Designers place staircases in central voids with natural light and clear visibility. Elevators recede into secondary zones.

This approach uses interior design to gently influence choices. Spatial layout, floor sequencing, and circulation paths reduce reliance on mechanical systems. They also cut energy use and support sustainability. The building does not force behavior. It simply makes the preferred action the easiest.

Planning, vertical zoning, and circulation are now core tools not afterthoughts.

Both cities confirm a shared principle: operational architecture actively shapes urban economics, environmental performance, and human conduct. Planning strategies increasingly treat movement systems as essential infrastructure.

This evolution marks a new phase in practice. Design now intersects with engineering, energy management, and behavioral science. Rising pressures from density, sustainability, and operating costs mean future architecture must perform as an integrated system. Form alone no longer suffices.

Architectural Snapshot

Operational architecture redefines the relationship between form and function in an era of continuous movement.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

High frequency mobility patterns, extended operating hours, and efficiency targets shape urban behavior in Tokyo and Sydney. Transit reliance, wellness metrics, and energy cost control precede architectural decisions, defining how movement is compressed and made predictable.

Regulatory frameworks enforce throughput, safety, and operational continuity. Tokyo’s zoning enables vertical stacking linked to transit nodes, while Australian codes reward reduced mechanical dependence and energy optimization. Risk management prioritizes minimizing peak-load friction over spatial flexibility.

Economic pressures reinforce these strategies. Capital expenditure avoidance and lifecycle efficiency push developers toward self-regulating spatial arrangements. Time savings, reduced staffing, and measurable performance outweigh symbolic design choices.

Architecture emerges last as an operational interface. Tokyo’s vertical flow segregation and Sydney’s behavior guiding circulation are not stylistic; they are the inevitable result of mobility demand, regulatory incentives, and efficiency driven economics converging in dense urban systems.

★ ArchUp Technical Analysis

ArchUp: Technical Analysis of Operational Architecture Models in Tokyo and Sydney

This article provides a technical analysis of two urban models in Tokyo and Sydney for the year 2026, serving as a case study in the transformation of architecture into movement and energy management systems. To enhance archival value, we present the following key technical and operational data:

The Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) model in Tokyo is based on vertically integrated multifunctionality. Projects integrate train stations (such as JR lines or metro) with office and commercial towers within a single structure, allocating separate levels for pedestrian, vehicular, and logistics movement. This separation aims to reduce transfer time between transportation modes and final destinations to under 5 minutes and increase public transport usage to over 70% among the complex’s residents and visitors.

In contrast, the internal behavior guidance model in Sydney focuses on energy efficiency and in-building movement. Internal staircases are designed to be more visible and attractive than elevators by placing them in central atriums with natural light levels up to 300 lux, while elevators are situated in secondary areas. This design aims to reduce the building’s energy dependence on elevators by up to 25% and encourage active movement.

The operational performance of both models is characterized by quantitative benchmarks. In Tokyo, success is measured by the reduction of commute times during peak hours and operational smoothness with densities reaching over 10,000 people per hour at the integrated station. In Sydney, the success of interior design is measured by the ratio of staircase use versus elevator use and the reduction in the building’s energy consumption per square meter.

Related link: Please review this article for an analysis of another urban project redefining the relationship between infrastructure and the urban fabric:

Urban Infrastructure: Inauguration of the Central Bypass in Cologne.

✅ Official ArchUp Technical Review completed for this article.