Salvator Mundi

Salvator Mundi (Latin for ”Savior of the World”) is a painting attributed in whole or in part to the Italian High Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci, dated to c. 1499–1510.[n 1] Long thought to be a copy of a lost original veiled with overpainting, it was rediscovered, restored, and included in a major exhibition of Leonardo’s work at the National Gallery, London, in 2011–2012.[2] Christie’s claimed just after selling the work that most leading scholars consider it to be an original work by Leonardo, but this attribution has been disputed by other specialists, some of whom posit that he only contributed certain elements.

The painting depicts Christ in an anachronistic blue Renaissance dress, making the sign of the cross with his right hand, while holding a transparent, non-refracting crystal orb in his left, signaling his role as Salvator Mundi and representing the ‘celestial sphere’ of the heavens. Approximately thirty copies and variations of the work by pupils and followers of Leonardo have been identified.[3] Proposed preparatory chalk and ink drawings of the drapery by Leonardo are held in the British Royal Collection.

The painting was sold at auction for US$450.3 million on 15 November 2017 by Christie’s in New York to Prince Badr bin Abdullah, setting a new record for the most expensive painting ever sold at public auction. Prince Badr allegedly made the purchase on behalf of Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism,[4][5] but it has since been posited that he may have been a stand-in bidder for his close ally, the Saudi Arabian crown prince Mohammed bin Salman.[6] This follows reports in late 2017 that the painting would be put on display at the Louvre Abu Dhabi[7][8] and the unexplained cancellation of its scheduled unveiling in September 2018.[9] The current location of the painting has been reported as unknown,[6] but a report in June 2019 stated that it was being stored on bin Salman’s yacht, pending the completion of a cultural center in Al-`Ula,[10] and a report of October 2019 indicated that it may be in storage in Switzerland.[11]

History

c. 1908–1910 photograph showing overpainting

Sixteenth century

Because of the specificity of the subject, Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi was probably commissioned by a specific patron rather than produced on speculation.[12] Art historians have suggested several possibilities for who the patron may have been and when the work was executed. Joanne Snow-Smith has argued that Leonardo painted the Salvator Mundi for Louis XII of France and his consort, Anne of Brittany.[13] Christie’s has stated that it was probably commissioned around 1500, shortly after Louis conquered the Duchy of Milan and took control of Genoa in the Second Italian War; Leonardo himself moved from Milan to Florence in 1500.[14][15] The art historian Luke Syson agrees, dating the painting to c. 1499, though Martin Kemp and Frank Zöllner date the work to c. 1504–1510 and c. 1507 or later respectively.[n 1] Martin Kemp discusses the possibilities of Isabella d’Este,[n 2] the Hungarian king Matthias Corvinus, Charles VIII of France and others as possible patrons, but does not draw conclusions.[16]

The painting would have been used in the context of personal devotion, as were other panels of this size and subject in the sixteenth century.[17][13] Indeed, Snow-Smith emphasizes in her writings the devotional relationship that Louis XII had with the Salvator Mundi as a subject[18][n 3] and Frank Zöllner discussed the painting’s relationship to French illuminated manuscripts in the practice of early sixteenth-century personal devotion and prayer.[22] It is possible that the painting was recorded in a 1525 inventory of Salaì’s estate as “Christo in mondo de uno Dio padre“, though it is unclear to which Salvator Mundi this might refer.[12] The provenance of the painting breaks after 1530.[3]

Origins

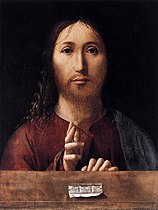

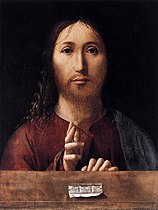

The Salvator Mundi as an image type predates Leonardo. Thus, Martin Kemp argues that on one hand Leonardo was constrained in his composition by the expected iconography of the Salvator Mundi, but on the other hand he was able to use the image as a vehicle for spiritual communication between the spectator and the likeness of Christ.[17] The composition has its sources in Byzantine art, the imagery of which further developed in northern Europe before finding its place in the Italian states.[n 4] Snow-Smith relates the development of the Salvator Mundi to Byzantine iconography and narratives of images of Christ “not made by human hands”.[24] Such acheiropoeta would include the Mandylion of Edessa, the Keramidion, and the Veil of Veronica.[25] Although the Salvator Mundi has its origins in the acheiropoeta, Snow-Smith discusses, the Salvator Mundi emerged in the fifteenth century through such intermediate subjects as Christ as Pantocrator, Christ in Majesty, and The Last Judgement, which like the acheiropoeta betray their Byzantine origins through their frontal depictions of Christ.[26] The frontality of Christ is shared by other images of Christ and God the Father in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, including in ‘portrait’ images of Christ, which feature only Christ at half-length and without the orb or blessing gesture, as well as in images of ‘Christ Blessing’ which does not show Christ holding an orb.[27] Images of Christ holding a sphere became widely popular following Charlemagne’s adoption of the globus cruciger and the scepter.[27][n 5] The earliest true Salvator Mundi images are found in northern Europe.[n 6] Indeed, the iconography of the Salvator Mundi came to fruition in paintings such as Robert Campin’s Blessing Christ and Praying Virgin and in the central panel of Rogier van der Weyden’s Braque Triptych, before such images became common in Italy later in the fifteenth century.[n 7] Works by such artists as Antonello da Messina and his Christ Blessing betray the influence of Northern artists in the Italian states.[29][30]

The earliest Italian example of a Salvator Mundi is likely to be Simone Martini’s Salvator Mundi Surrounded by Angels at the Palais des Papes, Avignon. This image shows Christ at full length rather than the bust-length portrayals of later paintings of the Salvator Mundi.[n 8] The image of Salvator Mundi later became well known in Italy, and especially Venice, through the archetype from Giovanni Bellini, now known only through copies.[30] This includes Andrea Previtali’s painting at the National Gallery, London.[31] Another fifteenth-century example can be seen in the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino in the very damaged painting by Melozzo da Forlì. It has been suggested that Leonardo based his composition on this specific example.[13][29][n 9]

Copies

There are at least thirty copies and variations of the painting executed by Leonardo’s pupils and followers, as counted by Robert Simon.[3][n 10] The large number of these paintings is an important part of the pedigree of Leonardo’s painting[3] and emphasizes that there must have been an original by Leonardo from which they were copied.[34] The most significant and widely discussed among these is the painting formerly in the de Ganay collection, as this one shares most closely the same composition and demonstrates the highest technical skill of Leonardo’s pupils. This is so much the case that Joanne Snow-Smith proposed it to be the original painting in 1978.[34][35][n 11] The many other copies found in Naples, Detroit, Warsaw, Zürich and other public and private collections contain various attributions to members of Leonardo’s pupils and followers.[34][38] Some versions differ significantly from the original. Two examples can be found in the form of a ‘portrait’ such as in Salaí’s 1511 painting, as well as in a painting sold at Sotheby’s on 5 December 2018, both of which use Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi as their model but which do not employ the iconography of the blessing hand or globe.[n 12] Other artists use the same model but for other subjects, as is the case with Leonardo’s Spanish follower Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina and the Eucharistic Christ now at the Museo del Prado.[40]

Leonardo’s studio and his followers likewise produced at least four Salvator Mundi panels depicting a youthful Christ who is less frontal in his pose and who holds a terrestrial globe.[41][n 13] These are largely from Leonardo’s Milanese following rather than from members of his studio,[43][n 14] though the variant in Rome can reasonably be attributed to his pupil Marco d’Oggiono.[n 15]

Wenceslaus Hollar, Salvator Mundi (1650), engraving, inscribed in Latin: “Leonardo da Vinci painted it, … from the original …”,[n 16] Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library[47]

Seventeenth to nineteenth centuries

This painting seems to have been at James Hamilton’s Chelsea Manor in London from 1638 to 1641. After participating in the English Civil War, Hamilton was executed on 9 March 1649 and some of his possessions were taken to the Netherlands to be sold.[47] The Bohemian artist Wenceslaus Hollar could have made his engraved copy, dated 1650, in Antwerp at that time.[14][n 17] It was also recorded in Henrietta Maria’s possession in 1649,[47][n 18] the same year her husband Charles I was executed, on 30 January. The painting was included in an inventory of the Royal Collection,[n 19] valued at £30, and Charles’s possessions were put up for sale under the English Commonwealth. The painting was sold to a creditor in 1651, returned to Charles II after the English Restoration in 1660,[51] and included in an inventory of Charles’s possessions at the Palace of Whitehall in 1666. It was inherited by James II, and may have remained with him until it passed to his mistress Catherine Sedley,[14] whose illegitimate daughter with James became the third wife of John Sheffield, Duke of Buckingham. The duke’s illegitimate son, Sir Charles Herbert Sheffield, auctioned the painting in 1763[51] along with other artworks from Buckingham House when the building was sold to George III.

The painting was probably placed in a gilded frame in the nineteenth century, in which it remained until 2005.[52] It is probably the painting bought by the British collector Francis Cook in 1900 for his collection at Doughty House in Richmond, London.[53] The painting had been damaged by previous restoration attempts and was attributed to Bernardino Luini, a follower of Leonardo.[51] Sir Francis Cook, 4th Baronet, Cook’s great-grandson, sold it at auction in 1958 for £45[54] as a work by Leonardo’s pupil Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, to whom the painting remained attributed until 2011.[55]

Rediscovery and restoration

The painting as it appeared in a 2005 auction house catalog, where it was listed as “After Leonardo da Vinci” and estimated at $1,200–$1,800[56]

The original painting by Leonardo himself was thought to have been destroyed or lost in around 1603.[57] In 1978, Joanne Snow-Smith argued that the copy in the collection of the Marquis Jean-Louis de Ganay in Paris was the lost original, based on, among other things, its similarity to Leonardo’s Saint John the Baptist.[n 21] While Snow-Smith was thorough in her research in regards to the provenance of the painting and its relationship to Hollar, few art historians were convinced of her attribution.[36][n 22]

In 2005, a Salvator Mundi was presented and acquired at an auction for less than $10,000 (€8,450) by a consortium of art dealers that included Alexander Parrish and Robert Simon,[60] a specialist in Old Masters.[61][62] It was sold from the estate of the Baton Rouge businessman Basil Clovis Hendry Sr.,[63] at the St. Charles Gallery auction house in New Orleans. It had been heavily overpainted, to the point where the painting resembled a copy, and was, before restoration, described as “a wreck, dark and gloomy”.[64]

The consortium believed there was a possibility that this seemingly low-quality work might be Leonardo’s long-missing original;[65] as a consequence, they commissioned Dianne Dwyer Modestini at New York University to oversee the restoration. When Modestini began removing the overpainting with acetone at the beginning of the restoration process, she discovered that at some point a stepped area of unevenness near Christ’s face had been shaved down with a sharp object, and also leveled with a mixture of gesso, paint, and glue.[52] Using infrared photographs Simon had taken of the painting, Modestini discovered a pentimento (a trace of an earlier composition), which had the blessing hand’s thumb in a straight, rather than curved, position.[52] The discovery that Christ had two thumbs on his right hand was crucial. This pentimento showed that the original artist had reconsidered the position of the figure; such a second thought is considered evidence of an original, rather than a copy, as a painting copied from the finished original would not have such an alteration partway through the painting process.[8]

Modestini proceeded to have the panel specialist Monica Griesbach chisel off a woodworm-infested marouflaged panel, which had caused the painting to break into seven pieces. Griesbach reassembled the painting with adhesive and wood slivers.[52] In late 2006, Modestini began her restoration effort.[52] The art historian Martin Kemp was critical of the result: “Both thumbs” of the painting’s raw state “are rather better than the one painted by Dianne”.[8] The work was subsequently authenticated as a painting by Leonardo.[62][64] From November 2011 through February 2012, the painting was exhibited at the National Gallery, London, as an autograph work by Leonardo, after authentication by that gallery. In 2012, it was also authenticated by the Dallas Museum of Art.[60][62][66][n 23]

In May 2013, the Swiss dealer Yves Bouvier purchased the painting for just over US$75 million in a private sale brokered by Sotheby’s, New York. The painting was then sold to the Russian collector Dmitry Rybolovlev for US$127.5 million.[68][69][70] The price that Rybolovlev paid was therefore significantly higher, well beyond the 2 percent commission Bouvier was supposed to receive, according to Rybolovlev himself.[71][72][73] Consequently, this sale—along with several other sales Bouvier made to Rybolovlev—created a legal dispute between Rybolovlev and Bouvier,[74] as well as between the original dealers of the painting and Sotheby’s. In 2016, the dealers sued Sotheby’s for the difference of the sale, arguing that they were shortchanged. The auction house has denied knowing that Rybolovlev was the intended buyer, and sought to dismiss the lawsuit.[75] In 2018, Rybolovlev also sued Sotheby’s for $380 million, alleging that the auction house knowingly participated in a defrauding scheme by Bouvier, in which the painting played a part.[76] Uncovered email exchanges between Bouvier and the auction house seemed to confirm this, according to Rybolovlev’s lawyers.[77]

Christie’s auction

The painting was exhibited in Hong Kong, London, San Francisco, and New York in 2017, and then sold at auction at Christie’s in New York on 15 November 2017 for $450,312,500,[n 24] a new record price for an artwork (the hammer price was $400 million, plus $50.3 million in fees).[81][82] The purchaser was identified as the Saudi Arabian prince Badr bin Abdullah.[83][84] In December 2017, The Wall Street Journal reported that Prince Badr was an intermediary for Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.[85] However, Christie’s confirmed that Prince Badr acted on behalf of Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism for display at the Louvre Abu Dhabi.[4][86] In September 2018, the exhibition was indefinitely postponed,[87] and a news report of January 2019 noted that “no one knows where it is, and there are grave concerns for its physical safety”.[60] Georgina Adam, editor at large of The Art Newspaper, dismissed these reports, stating that “We believe it’s in storage in Geneva.”[88] In June 2019, the painting was reported to be on a luxury yacht belonging to bin Salman, sailing on the Red Sea.[89]

The painting again failed to appear in the Louvre’s Paris exhibition of Leonardo works, held from 24 October 2019 to 24 February 2020. The exhibition displayed 11 paintings by Leonardo, of the fewer than 20 known to survive, but not the Salvator Mundi.[90][91] However, the 46-page booklet that accompanied the exhibition – briefly available in the museum bookshop – detailed the Louvre’s scientific examinations and concluded that “the results of the historical and scientific study … allow us to confirm the attribution of the work to Leonardo da Vinci”.[92][93] In June 2021, The Observer newspaper quoted skeptical comments about the sale from Robert King Wittman, a former FBI art crime specialist: “Why anyone would pay that kind of money for a piece that had questions about it is very strange. That particular painting is not worth what was paid for it. So there is a suspicious aspect to it. And the provenance is very murky.”[94]

Attribution

About a year into her restoration effort, Dianne Dwyer Modestini noted that color transitions in the subject’s lips were “perfect” and that “no other artist could have done that”. Upon studying the Mona Lisa for comparison, she concluded that “The artist who painted her was the same hand that had painted the Salvator Mundi“.[52] Since then, she has disseminated high-resolution images and technical information online for the scholarly community and public.[95]

In 2006 Nicholas Penny, director of the National Gallery, wrote that he and some of his colleagues considered the work an autograph Leonardo, but that “some of us consider that there may be [parts] which are by the workshop”.[52] Penny conducted a side-by-side study of the Salvator Mundi and the Virgin of the Rocks in 2008. Martin Kemp later said of the meeting, “I left the studio thinking Leonardo must be heavily involved”, and that “No one in the assembly was openly expressing doubt that Leonardo was responsible for the painting.”[52] In a 2011 consensus decision facilitated by Penny, the attribution to Leonardo was agreed upon unequivocally.[55][96] By July 2011, separate press release documents were issued by the owners’ publicity representative and the National Gallery, officially announcing the “new discovery”.[55][97]

Christ’s hands, the curls of his hair, and his drapery are well preserved, close to their original state.[98]

Once it was cleaned and restored, the painting was compared with, and found superior to, twenty other versions of the composition. It was on display in the National Gallery’s exhibition Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan from November 2011 to February 2012.[14][64][99][100] Several features in the painting have led to the positive attribution: a number of pentimenti are evident, most notably the position of the right thumb. The sfumato effect of the face—evidently achieved in part by manipulating the paint using the heel of the hand—is typical of many works by Leonardo.[101] The way the ringlets of hair and the knotwork across the stole have been handled is also seen as indicative of Leonardo’s style. Furthermore, the pigments and the walnut panel upon which the work was executed are consistent with other Leonardo paintings.[102] Additionally, the hands in the painting are very detailed, something for which Leonardo is known: he would dissect the limbs of the deceased in order to study them and render body parts in an extremely lifelike manner.[103]

One of the world’s leading Leonardo experts, Martin Kemp,[104][105] who helped authenticate the work, said that he knew immediately upon first viewing the restored painting that it was the work of Leonardo: “It had that kind of presence that Leonardos have … that uncanny strangeness that the later Leonardo paintings manifest.” Of the better-preserved parts, such as the hair, Kemp notes: “It’s got that kind of uncanny vortex, as if the hair is a living, moving substance, or like water, which is what Leonardo said hair was like”.[101] Kemp also states:

However skilled Leonardo’s followers and imitators might have been, none of them reached out into such realms of “philosophical and subtle speculation”. We cannot reasonably doubt that here, we are in the presence of the painter from Vinci.[106]

Pentimenti visible in the palm of the left hand shown through the transparent orb may be evidence of Leonardo’s authorship.[98]

In his biography of Leonardo, Walter Isaacson notes that the celestial sphere that Christ is holding does not correspond to the way such an orb would realistically look.[107] It also shows no reflection.[108] Isaacson writes that

In one respect, it is rendered with beautiful scientific precision, but Leonardo failed to paint the distortion that would occur when looking through a solid clear orb at objects that are not touching the orb. Solid glass or crystal, whether shaped like an orb or a lens, produces magnified, inverted, and reversed images. Instead, Leonardo painted the orb as if it were a hollow glass bubble that does not refract or distort the light passing through it.[109]

Isaacson believes that this was “a conscious decision on Leonardo’s part”,[110] and speculates that either Leonardo felt a more accurate portrayal would be distracting, or that “he was subtly trying to impart a miraculous quality to Christ and his orb.”[109] Kemp agrees that “To show the full effects of the sphere on the drapery behind would have been grotesque in a functioning devotional image”.[108] Kemp further states that the doubled outline of the heel of the hand holding the sphere—which the restorer described as a pentimento—is an accurate rendering of the double refraction produced by a transparent calcite (or rock crystal) sphere.[n 25][101] However, this continues outside the globe itself.[108] Kemp further notes that the orb “sparkles with a series of internal inclusions (or pockets of air)”—evidence in support of its being solid.[111] More recently, the globe has been also interpreted as a magnifying instrument consisting of a vitreous globe filled with water (which in nature would also distort the background).[112][108] André J. Noest suggests that the three painted specks represent celestial bodies.[108]

Other versions or copies of the Salvator Mundi often depict a brass, solid spherical orb, terrestrial globe, or globus cruciger; occasionally, they appear to be made of translucent glass, or show landscapes within them. The orb in Leonardo’s painting, Kemp says, has “an amazing series of glistening little apertures—they’re like bubbles, but they’re not round—painted very delicately, with just a touch of impasto, a touch of dark, and these little sort of glistening things, particularly around the part where you get the back reflections”. These are the characteristic features of rock crystal, on which Leonardo was an avid expert. He had been asked to evaluate vases that Isabella d’Este[n 26] had thought of purchasing, and greatly admired the properties of the mineral.[101]

Iconographically, the crystal sphere relates to the heavens.[111][98] In Ptolemaic cosmology, the stars were embedded in a fixed celestial crystalline sphere (composed of aether), with the spherical Earth at the center of the universe. “So what you’ve got in the Salvator Mundi“, Kemp states, “is really ‘a savior of the cosmos’, and this is a very Leonardesque transformation.”[101]

Leonardo’s Paris Manuscript D, 1508–09[115]

Another aspect of Leonardo’s painting Kemp studied was depth of field, or shallow focus. Christ’s blessing hand appears to be in sharp focus, whereas his face—though altered or damaged to some extent—is in soft focus. In his manuscript of 1508–1509 known as Paris Manuscript D,[116] Leonardo explored theories of vision, optics of the eye, and theories relating to shadow, light, and color. In the Salvator Mundi, he deliberately placed an emphasis on parts of the picture over others. Elements in the foreground are seen in focus, while elements further from the picture plane, such as the subject’s face, are barely in focus. Paris Manuscript D shows that Leonardo was investigating this particular phenomenon around the turn of the century. Combined, the intellectual aspects, optical aspects, and the use of semi-precious minerals are distinctive features of Leonardo’s oeuvre.[101]

“There is extraordinary consensus it is by Leonardo,” said the former co-chairman of old master paintings at Christie’s, Nicholas Hall: “This is the most important old master painting to have been sold at auction in my lifetime.”[118] Christie’s lists the ways scholars confirmed the attribution to Leonardo da Vinci:

The reasons for the unusually uniform scholarly consensus that the painting is an autograph work by Leonardo are several, including the previously mentioned relationship of the painting to the two autograph preparatory drawings in Windsor Castle; its correspondence to the composition of the ‘Salvator Mundi’ documented in Wenceslaus Hollar’s etching of 1650; and its manifest superiority to the more than 20 known painted versions of the composition.

Furthermore, the extraordinary quality of the picture, especially evident in its best-preserved areas, and its close adherence in style to Leonardo’s known paintings from circa 1500, solidifies this consensus.[14][119]

According to Robert Simon, “Leonardo painted the Salvator Mundi with walnut oil rather than linseed oil, as all the other artists in that period did … In fact, he wrote about using walnut oil, as it was a new advanced technique.”[120] Simon also states that ultraviolet imaging reveals that the darker areas of the painting are mostly owing to the restoration; the rest is original paint.[121]

The art critic Ben Lewis, who disputes a full attribution to Leonardo, admits that his authorship of the work is possible, owing to the originality of the face, which has “something modern about it”.[121] Kemp says:

I don’t rule out the possibility of studio participation … But I cannot define any areas that I would say are studio work.[122]

An examination of the painting had been conducted by the Louvre’s laboratory C2RMF in June 2018. A publication was prepared by the Louvre and printed in December 2019 in case the Louvre had the chance to present the painting in its exhibition, and was temporarily available in the Louvre bookshop. It contains essays by Vincent Delieuvin, the chief curator of paintings at the Louvre, and Myriam Eveno and Elisabeth Ravaud from the Louvre’s laboratory C2RMF. In his preface, the museum’s director Jean-Luc Martinez states that “The results of the historical and scientific study presented in this publication allow us to confirm the attribution of the work to Leonardo da Vinci, an appealing hypothesis which was initially presented in 2010 and which has sometimes been disputed”.[93][92][123][124] Delieuvin differentiated the picture from other studio versions – including the Ganay version that appeared in the Louvre’s Leonardo exhibition – by the presence of subtle underpainting, numerous pentimenti, and pictorial quality. He concludes:

All these factors invite us to privilege the idea of a work that is entirely autograph, sadly damaged by the poor conservation of the work and by previous restorations which were too brutal.[93]

In the discussion of the scientific evidence, Ravaud and Eveno write:

The examination of the Salvator Mundi seems to us to demonstrate that the painting was indeed executed by Leonardo. It is essential in this context to distinguish the original parts from those that have been changed or repainted and this is indeed what was carried out during this study notably by using X florescence. Examination under a microscope revealed very skillful execution, notably in the skin colouring and in the curls of the hair, and great refinement notably in the depiction of the relief of the embroidery [knotwork].

Radiography showed up the same very faint outlines as in the St. Anne, Mona Lisa and St. John the Baptist, characteristic of Leonardo’s work after 1500. The number of changes made during the creation of the work also plead in favour of an autograph work. The first version of the central ‘plastron’ with a pointed form, is immediately comparable to the central part of the tunic in the Windsor drawing and to our knowledge is not seen anywhere else.

In addition, the movement of the thumb was also noted in the St. John by Leonardo. After intensive studies of the other Leonardo works in the Louvre’s collection it seems to us that a number of the techniques observed in the Salvator Mundi are typical of Leonardo—the originality of the preparation, the use of ground glass and the remarkable use of vermillion in the hair and shadows. These latest elements all plead in favour of a late work by Leonardo, after St. John the Baptist, and dating from the second Milan period.[93]

Partial attribution

Some respected experts on Renaissance art question the full attribution of the painting to Leonardo.[125][110][126] Jacques Franck, a Paris-based art historian and Leonardo specialist who has studied the Mona Lisa out of the frame multiple times, stated: “The composition doesn’t come from Leonardo, he preferred twisted movement. It’s a good studio work with a little Leonardo at best, and it’s very damaged. It’s been called ‘the male Mona Lisa’, but it doesn’t look like it at all.”[118]

Michael Daley, the director of ArtWatch UK, doubts the Salvator Mundi‘s authenticity and theorizes that it may be the prototype of a subject painted by Leonardo:[127][128] “This quest for an autograph prototype Leonardo painting might seem moot or vain: not only do the two drapery studies comprise the only accepted Leonardo material that might be associated with the group, but within the Leonardo literature there is no documentary record of the artist ever having been involved in such a painting project.”[127]

Carmen Bambach, a specialist in Italian Renaissance art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, questioned full attribution to Leonardo: “having studied and followed the picture during its conservation treatment, and seeing it in context in the National Gallery exhibition, much of the original painting surface may be by Boltraffio, but with passages done by Leonardo himself, namely Christ’s proper right blessing hand, portions of the sleeve, his left hand and the crystal orb he holds.”[129][130] In 2019, Bambach criticised Christie’s for its claim that she was one of the experts who had attributed the painting to Leonardo. In her 2019 book Leonardo da Vinci Rediscovered, she is even more specific, attributing most of the work to Boltraffio, “with only ‘small retouchings’ by the master himself”.[131]

Matthew Landrus, an art historian at the University of Oxford, agreed with the concept of parts of the painting being executed by Leonardo (“between 5 and 20%”), but attributes the painting to Leonardo’s studio assistant Bernardino Luini, noting Luini’s ability in painting gold tracery.[132]

Frank Zöllner, the author of the catalogue raisonné Leonardo da Vinci. The Complete Paintings and Drawings.[133] writes:

Over-cleaning resulted in abrasion over the entire painting, especially in the face and hair.[118] Above Christ’s left eye (right) are visible marks that the artist made to soften the flesh with the heel of his hand.[98]

This attribution is controversial primarily on two grounds. Firstly, the badly damaged painting had to undergo very extensive restoration, which makes its original quality extremely difficult to assess. Secondly, the Salvator Mundi in its present state exhibits a strongly developed sfumato technique that corresponds more closely to the manner of a talented Leonardo pupil active in the 1520s than to the style of the master himself. The way in which the painting was placed on the market also gave rise to concern.[127][133][134]

Zöllner also explains that the quality of Salvator Mundi surpasses other known versions; however,

[It] also exhibits a number of weaknesses. The flesh tones of the blessing hand, for example, appear pallid and waxen as in a number of workshop paintings. Christ’s ringlets also seem to me too schematic in their execution, the larger drapery folds too undifferentiated, especially on the right-hand side … It will probably only be possible to arrive at a more informed verdict on this question after the results of the painting’s technical analyses have been published in full.[127][133][135]

In Paris, the Louvre’s request for the Salvator Mundi to be exhibited in its Leonardo da Vinci exhibition of 2019–2020[136] was reportedly met without response.[137] The New York Times reported in April 2021 that the non-appearance was because the French were unwilling to meet Saudi demands that the painting be hung alongside the Mona Lisa.[138] The Louvre’s inability to comment on the matter in the interim, however, led to speculation that its absence was due to doubts over its full attribution to the artist.[138][139] Kemp disputed this reasoning, saying:

It’s simply untrue … because even if the Louvre was persuaded that there was studio participation in the picture, which would be feasible and not unknown after all, it wouldn’t stop them from showing it. It’s a major picture, an important thing. The story is sensationalized and inaccurate.[140]

Rejection of attribution

The British art historian Charles Hope dismissed the attribution to Leonardo entirely in a January 2020 analysis of the painting’s quality and provenance. He doubted that Leonardo would have painted a work where the eyes were not level and the drapery undistorted by a crystal orb. He added, “The picture itself is a ruin, with the face much restored to make it reminiscent of the Mona Lisa.” Hope condemned the National Gallery’s involvement in Simon’s “astute” marketing campaign.[141]

In August 2020, Jacques Franck, who had previously called the portrait “a good studio work with a little Leonardo at best,”[118] cited its “childishly conceived left hand”, as well as the “oddly long and thin nose, the simplified mouth [and] the over shadowy neck” as evidence that Leonardo did not paint it.[142] More precisely, Franck now attributes the painting to Salaì jointly with Boltraffio: in effect, the work’s infrared reflectogram betrays a very singular sketching-out technique, never seen in any of Leonardo’s original paintings, yet encountered in Salaì’s Head of Christ of 1511 in the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, a composition close to the Saudi Salvator Mundi and signed by the artist. This claim is also supported by the fact that a stricto sensu Salvator Mundi painting is recorded in Salai’s posthumous inventory of the estate established in Milan on 25 April 1525.[143]

In November 2020, a newly discovered drawing of Christ surfaced, possibly by Leonardo and with notable differences to the painting. According to the Leonardo scholar Annalisa Di Maria, “[This] is the true face of Salvator Mundi. [It] recalls everything in the drawings of Leonardo,” pointing to the similar three-quarters view used in his presumed self-portrait. She continued, “[Leonardo] could never have portrayed such a frontal and motionless character.” Kemp indicated that before he could review the drawing, he “would need to see if it is drawn left-handed.”[144]

Reception

The rediscovered painting by Leonardo generated considerable interest within the media and general public amid its pre-auction viewings in Hong Kong, London, San Francisco and New York, as well as after the sale. More than 27,000 people saw the work in person before the auction: the highest number of pre-sale viewers for an individual work of art, according to Christie’s.[125] The sale was the first time Christie’s had used an outside agency to advertise an artwork. Approximately 4,500 people stood in line to preview the work in New York the weekend prior to the sale.[125] The sensationalism of the painting following the sale led to it being a common subject in popular culture and discourse online. As Brian Boucher described, “the internet went a little bonkers” in response to the sale, leading to sarcastic and humorous comments and memes on Twitter, Instagram and other social media sites.[145] Similarly, Stephanie Eckardt noted how “the ongoing saga of Salvator Mundi indisputably” belongs in “the meme canon.”[146] In an article in the Art Market Monitor, Marion Maneker compared the sensationalism around Salvator Mundi to the media coverage surrounding the theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre in 1911. Just as the international media sensationalism lifted the painting to a high international status, she argued, so too did Christie’s marketing campaign and media sensationalism lead to its high sales price.[147] Alexandra Kim of the Harvard Crimson similarly described the reason for the painting’s newfound fame:

Why are we still so adamantly curious [about Salvator Mundi]? The New York Times, The Guardian, and more have covered this painting and its aftermath. It now seems that the drama surrounding this infamous painting has created a whole new work of art larger than the Salvator Mundi itself. The attention has grossly inflated its value: the more we discuss the work, the more curious we are, until it becomes a shining ball of artistic enlightenment.[148]

The narratives surrounding the painting have piqued the interest of filmmakers and playwrights. In July 2020, the company Caiola Productions announced that it was working on the production of a Broadway musical based on the history of Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi.[n 27] In April 2021, Antoine Vitkine directed a feature-length documentary entitled The Savior for Sale, focusing on the painting and its exclusion from the 2019–2020 Leonardo exhibition at the Louvre.[93] Shortly afterward, in June 2021, Andreas Koefoed’s documentary The Lost Leonardo premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival, exploring how the painting became the most expensive ever sold and then disappeared.[150][151]

Gallery

Copies and variations

-

School of Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi (c. 1503), private collection (formerly Marquis Jean-Louis de Ganay Collection).

-

Follower of Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi (1508–1513), Museum of San Domenico Maggiore, Naples.[152][153]

-

Follower of Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi (Cristo Redentore benedicente; early 16th century), Worsey Collection.

-

Giampietrino, Salvator Mundi (16th century), Detroit Institute of Arts.

-

Cesare da Sesto, Salvator Mundi (1516–1517), Wilanów Palace, Warsaw

-

Follower of Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi (16th century), Sammlung Stark, Zürich.

-

Lombard follower of Leonardo da Vinci (possibly Marco d’Oggiono), Salvator Mundi (16th century), private collection, formerly the Art Gallery of Ontario.[154]

-

Salaì, Head of Christ the Redeemer (1511), Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan.[155][156][27]

-

Milanese follower of Leonardo da Vinci, Bust of Christ (c. 1511–1513) private collection (Sotheby’s Old Masters Evening Sale 5 December 2018).[n 28]

-

Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina, The Eucharistic Christ (c. 1525), Museo del Prado, Madrid.[40]

Youthful Christ with a globe

-

Marco d’Oggiono, Salvator Mundi (c. 1500), Galleria Borghese, Rome.

-

School of Leonardo da Vinci, Le Sauveur du monde (c. 1505), Museum of Fine Arts of Nancy.

-

Giampietrino, Salvator Mundi, (early 16th century), Pushkin Museum, Moscow.

-

Follower of Leonardo da Vinci, Cristo giovanetto come Salvator Mundi, Museo Ideale Leonardo da Vinci.

Comparable examples

-

Unknown French Miniaturist, Pentecost from the Ingeborg Psalter (c. 1195), Musée Condé, Chantilly. (Ms. 9 fol. 32v.)[26]

-

Artist unknown, Miniature from a Flemish book of hours (Bruges), Salve Sancta Facies, Christ as Salvator Mundi (c. 1510) Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (Ms 15677, fol. 13v).[157][158]

-

Robert Campin, Blessing Christ and Praying Virgin Mary (c. 1425), Philadelphia Museum of Art.[159]

-

Rogier van der Weyden, Braque Triptych (central panel; c. 1452) Musée du Louvre, Paris.[160][161]

-

Antonello da Messina, Christ Blessing (1465), National Gallery, London.[29][30][162]

-

Simone Martini, Blessing Christ with Angels (c. 1341), Musée du Palais des Papes, Avignon.[26][163]

-

Andrea Previtali, Salvator Mundi (1519), National Gallery, London.[31]

-

Vittore Carpaccio, Salvator Mundi (c. 1510), Isaac Delgado Museum of Art, New Orleans.[164]

-

Melozzo da Forlì, Salvator Mundi (c. 1480–1482), Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Palazzo Ducale, Urbino.[165][166][29]

Notes

Sources

- Dalivalle, Margaret; Kemp, Martin; Simon, Robert (2019). Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi & the Collecting of Leonardo in the Stuart Courts. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-881383-5.

- Kemp, Martin (2019). Leonardo da Vinci: The 100 Milestones. New York, New York, US: Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4549-304-26.

- Marani, Pietro C. (2003) [2000]. Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings. New York, New York, US: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-3581-5.

- Snow-Smith, Joanne (1982). The Salvator Mundi of Leonardo da Vinci. Seattle: Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington. ISBN 978-0-935558-11-1.

- Syson, Luke; Keith, Larry; Galansino, Arturo; Mazzotta, Antoni; Nethersole, Scott; Rumberg, Per (2011). Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan. London, UK: National Gallery. ISBN 978-1-85709-491-6.

- Zöllner, Frank (2019) [2003]. Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings and Drawings (Anniversary ed.). Cologne, Germany: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-7625-3.

Further reading

- Alberti, Leon Battista. De Pictura. (Trans. Grayson). Phaidon. London. 1964. p. 63-4

- Allsop, Laura (7 November 2011). “Decoding da Vinci: How a lost Leonardo was found”. CNN.

- Ames-Lewis, Francis. The Intellectual Life of The Early Renaissance Artist. Abbeville Press. p. 18, 275

- Nicola Barbatelli, Carlo Pedretti, Leonardo a Donnaregina. I Salvator Mundi per Napoli Elio De Rosa Editore; CB Edizioni, 9 January 2017. ISBN 978-88-97644-38-5 (Italian)

- Elworthy, F. T. The Evil Eye The Classic Account of An Ancient Superstition. Courier Dover Publications. 2004 p. 293.

- Hankins, J. 1999. The Study of the Timaeus in Early Renaissance Italy. Natural Particulars: Nature and the Disciplines in Renaissance Europe. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kemp, Martin. Leonardo da Vinci: the marvellous works of nature and man. Oxford University Press. 2006. pp. 208–9

- Nicholl, Charles (17 April 2019). “The Last Leonardo by Ben Lewis review – secrets of the world’s most expensive painting | Art and design books”. The Guardian.

- Shaer, Matthew (14 April 2019). “The Invention of the ‘Salvator Mundi'”. Vulture. New York Magazine.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salvator Mundi by Leonardo Da Vinci. |

- Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi makes auction history, Christies.com

- Robert Simon, Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi

- Robert Simon, Leonardo da Vinci Painting Discovered, Painting Gains Attribution After Careful Scholarship and Conservation, press release, 7 July 2011

- H. Niyazi, Authorship and the dangers of consensus 11 July 2011

- Jean-Pierre Crettez, Internal geometry of “Salvator Mundi” (so-called Cook version, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci), 16 May 2019

Portals:

Leica collaborates with JMGO to launch 4K ultra-short-throw projector