The Tactile Resistance: Reclaiming Place in an Era of Global Architecture

The global pause of the COVID pandemic has provided an opportunity to assess present-day globalism and the architecture that has emerged alongside it. This homogenizing condition seems like the second coming of the midcentury International Style, only now with a far wider means of deployment. In response, we need to re-frame “global architecture” as “trans-national,” where the distinct nature of various cultures is maintained through an architecture that interprets and expresses a place-specific culture without resorting to sentimentality.

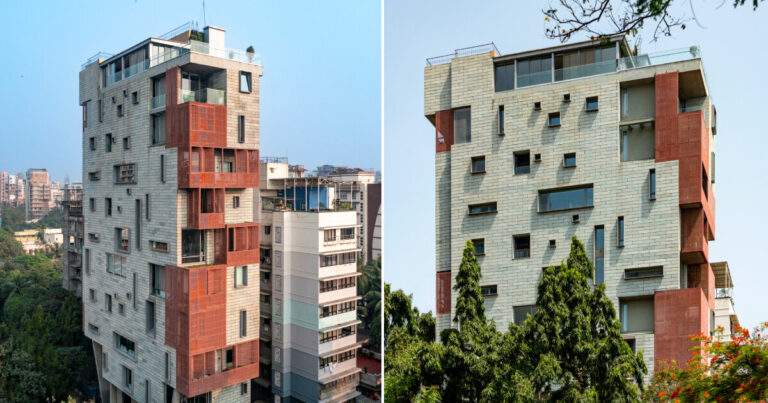

To counter placelessness, local architecture needs to focus on how we build, endowing it with a unique physicality not captured in today’s flat, virtual world. This should be embedded in its expression and experience through a focus on the tactile. For one, despite unfavorable life-safety codes and higher demand for comfort, we must push to implement strategies for natural ventilation and lighting, allowing us haptic engagement with our natural surroundings.

Another step is to celebrate building structures, expressing the local both in technique and material, reducing the need to clad and obscure. Equally significant is the rise of materials like CLT, which offer a inherent material warmth and texture.

In Philip Ursprung’s book Natural History, Herzog & de Meuron remind us that the one-on-one experience “is the first priority, and the only way architecture can compete with other media.” We need to push in the realm of reality where tactile experience is paramount. One can experience this power in Steven Holl’s Chapel of St. Ignatius, where the artisan bronze door pulls immediately feel upon touch that one is entering a specific place. But while hand-crafted items lend a unique tactility, they can also benefit from the facile customization that technology provides. The custom reception desk, colorful stairs, and interconnecting bridges at Gensler’s C-3 building are all areas of intimate contact that lend a unique spirit. Such custom items do not constitute a local architecture in themselves, but when aligned with the building’s vision they act at a tactile level to express that one is “here,” not somewhere else.

The challenge of bigness to local architecture exists, but is not insurmountable. The crafted brass doors and turnstiles of New York’s Rockefeller Center are intimately tied to its locale and to the human body, proving that even at a large scale, a tactile connection to place can be achieved.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

This article compellingly argues that the homogenizing force of global architecture must be countered by a trans-national focus on local culture, materiality, and, most importantly, tactile experience. While the critique of globalism is well-trodden, the piece effectively reframes Kenneth Frampton’s Critical Regionalism for the digital age, proposing tactility as a primary weapon against placelessness. However, it could more deeply address the significant economic and regulatory barriers that make this tactile approach a luxury rather than the norm. Nonetheless, its strength lies in moving beyond pure theory to offer tangible strategies from celebrating raw structure to championing custom fabrication that empower designers to create architecture that is truly felt, creating a vital and authentic sense of place.

Brought to you by the ArchUp Editorial Team

Inspiration starts here. Dive deeper into Architecture, Interior Design, Research, Cities, Design, and cutting-edge Projectson ArchUp.