Greenland Is Not Empty: Architecture, Isolation, and the Psychology of Space

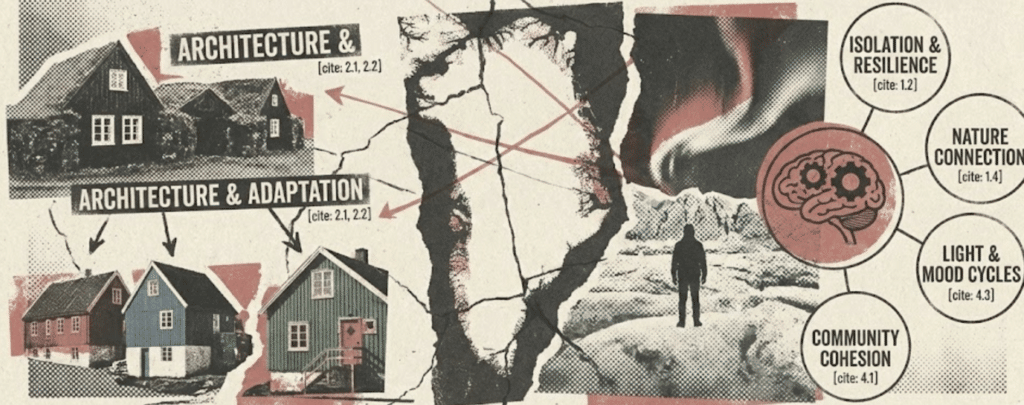

Greenland has recently re-entered the global conversation for reasons that have little to do with architecture, urban planning, or even everyday life. Political statements and speculative headlines, particularly regarding the Arctic’s rising geopolitical value in 2026, have pulled the island into the news cycle once again. But beyond the noise of resource extraction and territorial claims, Greenland presents a far more unsettling and important question. It is a question that the disciplines of architecture and urbanism cannot afford to ignore because it challenges the most fundamental assumptions about how space affects the human mind.

Greenland is often described by outsiders as vast and empty. This framing is fundamentally misleading. It is not empty. It is sparsely populated, intensely isolated, and spatially extreme. With a land area of over 2.16 million square kilometers and a population of roughly 56,000 people, Greenland possesses one of the highest land-area-per-capita ratios on Earth. In purely spatial terms, no country offers more land per person. Yet, Greenland also records one of the highest suicide rates globally, with figures often hovering between 80 and 100 per 100,000 people, a staggering multiple of the global average.

This contradiction forces a difficult inquiry into the nature of built environments. How can a territory with so much physical space produce such profound psychological compression?

The conventional answers tend to focus on the climate. We speak of the long Arctic winters, the limited sunlight, and the extreme cold. These factors are significant, but they are not sufficient explanations for the statistical reality. Other regions endure equally harsh environments without producing comparable social outcomes. Northern Japan, parts of Siberia, and high-altitude settlements in the Himalayas face environmental severity and economic pressure, yet they do not consistently exhibit the same patterns of structural despair. Something else is at play in Greenland, and it is rooted in the urban condition.

Greenland’s urban reality is not defined by density, but by fragmentation. Settlements are small, disconnected, and functionally dependent. There is no continuous urban fabric in the conventional sense. The 17 towns and roughly 60 settlements operate more like infrastructural outposts than cities. They are often accessible only by air or sea, with zero roads connecting one town to another. This lack of connectivity means that there is minimal redundancy in social spaces or economic programs.

Historically, much of the contemporary built environment in Greenland was shaped by the “G60” policy of the 1960s. This was a Danish modernization program designed to concentrate the population into larger towns to improve efficiency and services. Architecture became a tool of social engineering. The result was the construction of massive, industrial-scale apartment blocks, most notably the infamous Blok P in Nuuk, which once housed roughly one percent of the entire national population. These structures were built with the efficiency of Building Materials in mind, but they ignored the delicate social ecology of the Inuit culture they were housing.

Urban planning is not merely the distribution of buildings across land. It is the choreography of encounter. It determines how often people see each other, how friction is absorbed, and how loneliness is diluted. In Greenland, the extreme ratio of land to people does not translate into freedom. It often translates into a structural distance. When urban life lacks layering, and when daily routines offer few spontaneous interactions in the “space between,” isolation becomes an architectural byproduct. Space, in this context, does not heal. It amplifies.

Architecture in Greenland has historically responded to survival rather than civic life. Prefabrication and modular housing dominate the landscape because of logistical necessity. However, when buildings are conceived as provisional responses rather than long-term civic anchors, they rarely accumulate the layers of memory and identity required for social stability. This is a recurring theme in Architectural Research, where the permanence of the built environment is linked directly to collective mental health. Cities rely on repetition and ritual. They rely on places that do not disappear or reset.

Contrast this with the hyper-dense Cities of East Asia. In places like Tokyo or Hong Kong, space is a scarce commodity, yet social life is abundant. Crowding does not automatically generate despair. In many cases, it produces a form of collective resilience. The layered streets and mixed-use neighborhoods create constant, involuntary exposure to others. Even solitude, in such environments, is a choice. In Greenland, solitude is often an unavoidable geographical sentence.

“Denmark’s colonial strategy in Greenland was less an urban project than an administrative experiment: centralized settlements, standardized housing blocks, and welfare-driven planning were introduced to stabilize control rather than to cultivate endogenous urban life. While these policies improved healthcare, education, and basic infrastructure, they also accelerated cultural displacement and spatial dependency, producing towns that function administratively yet struggle socially and economically once external support recedes.”

The relationship between the suicide rate and urban form is not linear, but it is not coincidental either. Planning decisions shape mental health indirectly through access and rhythm. When a city lacks public interiors, transitional spaces, and civic redundancy, the individual bears the full weight of isolation alone. Greenland’s challenge is not land scarcity. It is relational scarcity. This raises a larger architectural question that extends far beyond the Arctic. Modern Architecture has long assumed that more space and lower density equal better living. The Greenlandic condition quietly dismantles that assumption. Space without social structure does not liberate. It disorients.

As global interest turns toward remote territories and the design of future settlements in extreme environments, Greenland offers a case study that must be studied with sobriety. The transition toward more sustainable and resilient Projects in the North must move beyond thermal efficiency. It must address the “social heat” of the space. Architecture cannot solve a psychological crisis alone, but it can either reinforce isolation or gently resist it. By failing to provide a layered civic life, the built environment in Greenland has, by omission, reinforced the former.

The lesson for the future of Sustainability in remote areas is uncomfortable but necessary. Human well-being is not a function of how much land we have, but of how carefully we organize the space between us. In the coming years, as we see more Competitions focused on extreme habitats, the focus must shift from the survival of the body to the survival of the community.

Greenland is not a warning about the climate. It is a warning about the limits of planning when it is stripped of its social dimensions. It reminds us that the most important infrastructure a city provides is the opportunity for one human being to see another. Without that, even the vastest landscape can feel like a cage.

✦ ArchUp Editorial Insight

Greenland’s urban condition is a clinical symptom of extreme geographic fragmentation and logistics-driven settlement policies. Analysis of mobility patterns reveals a total absence of terrestrial connectivity, forcing a reliance on air and sea nodes that institutionalize isolation. This framework was solidified by the historic G60 modernization policy, which prioritized administrative efficiency over the nuanced Spatial Dynamics of indigenous social structures. Consequently, procurement is dictated by restricted building seasons, necessitating modularity and Building Materials optimized for rapid assembly—a logic mirroring the standardized infrastructure of modern high-speed production. The architectural outcomes, such as industrial-scale apartment blocks, function as infrastructural outposts rather than civic anchors. These forms demonstrate how prioritizing thermal survival over the choreography of encounter produces psychological compression. In fragmented Cities, architecture becomes a geographical sentence when it fails to provide the layered redundancy essential for social stability, posing a critical challenge for extreme-environment Architectural Research.